Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- IRQ, Explained Like You’re Human

- What Actually Happens When an IRQ Fires?

- IRQ Numbers vs. Interrupt Vectors: The Naming Trap

- Types of IRQs and Interrupts You’ll Hear About

- IRQ Sharing: Why “Multiple Devices on the Same IRQ” Isn’t Automatically Bad

- Why IRQs Matter for Performance (Yes, Even If You’re “Not a Server Person”)

- How to Recognize an IRQ-Related Problem

- Interrupt Storms: When the Doorbell Gets Stuck

- Quick FAQ About IRQs

- Conclusion: IRQs Are the Computer’s “Now, Please” Button

- Real-World Experiences With IRQs (The “I Didn’t Know This Was a Thing” Edition)

- 1) “Why is my CPU at 30% when I’m doing nothing?”

- 2) “My audio crackles when I download a big file”

- 3) “Device Manager shows everything on the same IRQshould I be worried?”

- 4) “My embedded project worked… until I enabled one more interrupt”

- 5) “The mysterious ‘interrupt storm’ that turned a fast machine into a slow one”

Your computer is basically a very fast, very literal coworker. If you don’t tell it something happened, it will happily keep doing whatever it was doingforever.

So how does the CPU learn that your keyboard was pressed, a network packet arrived, or your SSD just finished reading data? That’s where an

Interrupt Request (IRQ) comes in: it’s the computer’s version of a doorbell that says, “Hey! I need attention. Like… now.”

IRQs are one of those “invisible plumbing” concepts that quietly make modern operating systems feel instant. When they work, you never notice them.

When they don’t, you get symptoms like stuttering audio, laggy input, weird device behavior, or that dreaded phrase from ancient troubleshooting lore:

“IRQ conflict.” (Cue dramatic thunder.)

IRQ, Explained Like You’re Human

An interrupt request (IRQ) is a signal that tells the CPU to temporarily pause what it’s doing so it can handle an important event.

That event usually comes from hardwarelike a mouse movement, a timer tick, or a network card receiving databut operating systems can also trigger

interrupt-like mechanisms for urgent software events.

The alternative to IRQs is polling, where the CPU repeatedly checks devices to see if they need attention. Polling works, but it’s inefficient:

it wastes CPU time asking “Are we there yet?” thousands or millions of times per second. With IRQs, devices only “speak up” when something actually happens.

What Actually Happens When an IRQ Fires?

Behind the scenes, an IRQ sets off a carefully choreographed routine. The exact details vary by CPU architecture and operating system, but the core idea is consistent.

1) A device raises its hand

A device detects an event (say, a packet arrives at your network interface) and sends an interrupt request. Historically, this could mean asserting a physical

interrupt line. On modern systems, it often means sending a special message over the bus (more on MSI/MSI-X later).

2) The interrupt controller routes it

The system’s interrupt controller receives the request and decides where it should go. In modern PCs, this typically involves

APIC/IO-APIC logic that can route interrupts to specific CPU cores.

3) The CPU pauses and saves context

The CPU briefly stops the current instruction flow, saves enough state to resume later, and jumps to a predefined interrupt handling path.

Think of it like bookmarking the current page before answering the door.

4) The OS runs an interrupt handler (ISR)

The operating system (often through a device driver) runs an interrupt service routine (ISR) or handler. Good handlers do the minimum necessary:

confirm the interrupt is real, grab essential data, acknowledge the device/controller, and defer heavy work to a safer context (like a kernel thread).

5) The CPU resumes what it was doing

After handling the interrupt, the CPU restores the saved state and continues right where it left off, as if nothing happenedexcept now your input was processed,

your packet got queued, or your storage request completed.

IRQ Numbers vs. Interrupt Vectors: The Naming Trap

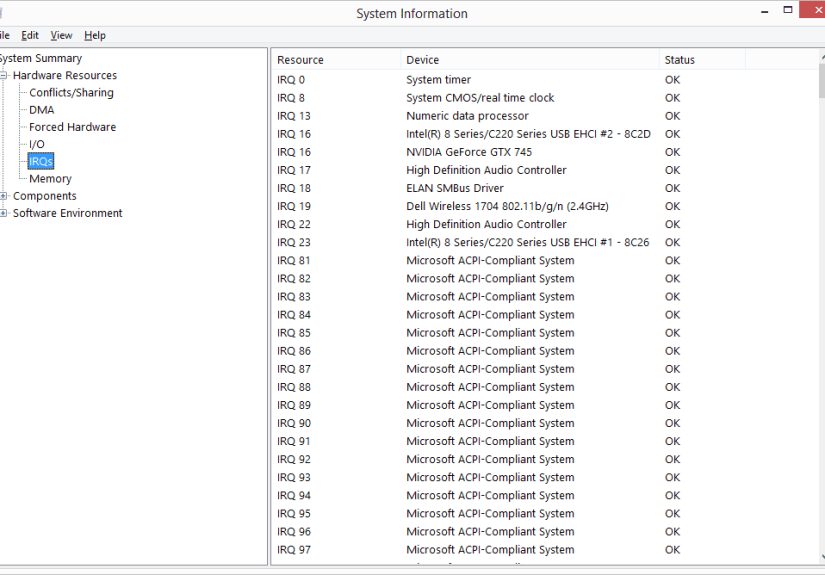

People casually say “IRQ 16” or “IRQ 9,” but there are two related (and often confused) ideas:

- IRQ lines/IDs: a way of identifying interrupt sources (historically physical lines, now often logical IDs).

- Interrupt vectors: the CPU’s entry pointsbasically “which handler do we jump to?”

On older PC hardware, IRQs were strongly associated with a small set of physical lines managed by legacy controllers. On modern systems, the mapping is far more flexible,

and what you see as an “IRQ number” may represent a routed interrupt or message signaled interrupt rather than a single shared wire.

The old-school era: PIC and the classic IRQ 0–15

Early x86 PCs used a Programmable Interrupt Controller (PIC) with a limited number of interrupt lines. That’s where the famous IRQ range

0 through 15 comes from in classic PC lore. Back then, resource conflicts were more common because there were fewer lanes for devices to shout through.

The modern era: APIC, IO-APIC, and “we have more lanes now”

Modern PCs use an Advanced Programmable Interrupt Controller (APIC) design that supports more interrupts and smarter routing, especially on multi-core CPUs.

This reduces the old “only 16 IRQs, good luck” pressure and makes interrupt distribution more flexible and scalable.

Types of IRQs and Interrupts You’ll Hear About

Maskable vs. non-maskable interrupts (NMI)

Many interrupts are maskable, meaning the CPU/OS can temporarily block them (for example, while performing a critical operation).

A non-maskable interrupt (NMI) is reserved for extremely high-priority eventsthink serious hardware faultswhere “please ignore this for a moment”

is not an acceptable life plan.

Edge-triggered vs. level-triggered

Edge-triggered interrupts fire on a transition (like “low → high”), while level-triggered interrupts remain asserted until serviced.

Level-triggered designs can be helpful but must be acknowledged correctlyotherwise you can get repetitive interrupts because the “I still need help” signal never clears.

Line-based interrupts (INTx) vs. message-signaled interrupts (MSI/MSI-X)

Historically, many devices used shared interrupt lines (often referred to as legacy INTx). On PCI/PCIe systems today, you’ll often see

Message Signaled Interrupts (MSI) or MSI-X, where a device triggers an interrupt by sending a message over the bus

rather than toggling a shared physical line.

MSI-style interrupts tend to reduce sharing headaches and scale better, especially for high-throughput devices (like fast NICs and storage controllers).

Hardware interrupts vs. software interrupts (and exceptions)

Hardware IRQs come from devices. Software-driven events can also cause interrupt-like transfers of control (system calls, traps, CPU exceptions).

The big difference is that hardware interrupts are asynchronousyour CPU didn’t “choose” the momentwhile software exceptions are usually tied to current execution.

IRQ Sharing: Why “Multiple Devices on the Same IRQ” Isn’t Automatically Bad

If you open a system tool and see multiple devices “sharing” an IRQ, don’t panic. On modern Plug and Play systemsespecially with ACPIIRQ sharing is often normal.

The operating system and firmware coordinate how interrupts are routed. Devices can share an interrupt path while still being handled correctly because drivers

can verify whether the interrupt was actually intended for them.

The key difference between “normal sharing” and “real trouble” is behavior:

- Normal: devices share an IRQ, everything works, performance is fine, no weird latency spikes.

- Trouble: an interrupt storm, buggy driver claiming interrupts incorrectly, misconfigured trigger mode, or a device that fails to acknowledge interrupts.

Why IRQs Matter for Performance (Yes, Even If You’re “Not a Server Person”)

Interrupt handling has a real cost. Each interrupt forces the CPU to switch context, run a handler, and manage scheduling side effects. Too many interrupts can:

- increase CPU overhead (especially at high packet or I/O rates),

- cause latency spikes (bad for audio, gaming input, real-time workloads),

- create uneven CPU usage if interrupts pile onto one core.

Interrupt affinity: which CPU core gets the knock?

On multi-core systems, interrupts can often be routed to specific cores. That can be a win:

one core handles most network interrupts while others run applicationsless contention, smoother performance.

It can also be a loss if everything lands on the same unlucky core like it’s the only one with a mailbox.

IRQ balancing: spreading the load

Many Linux systems use an IRQ balancing approach (often assisted by services like irqbalance) to distribute interrupts across cores.

This matters most for high-throughput devices (10GbE+ networking, storage, virtualization hosts), but it can also improve responsiveness on desktops under load.

Real-time systems: keeping interrupts predictable

In real-time or low-latency environments, IRQ behavior is treated like a first-class performance variable. Teams may isolate interrupts to specific CPUs, use threaded

interrupt handling strategies, and reduce jitter so time-sensitive tasks don’t get ambushed.

How to Recognize an IRQ-Related Problem

IRQs rarely “break” in isolation. More often, an IRQ issue is a symptom of a driver problem, a misbehaving device, or a configuration mismatch.

Common real-world signs include:

- random device disconnects or “device not responding” errors,

- audio crackling under load (latency spikes),

- network drops or unusually high CPU usage during traffic,

- system freezes when a specific device is active,

- logs mentioning interrupt storm or repeated interrupt handling messages.

Windows: what you’ll typically see

On Windows, you’ll often encounter IRQs in a “resources” context (Device Manager, driver docs, hardware debugging guides).

Modern Windows systems generally manage interrupt routing automatically, and manual reassignment is far less common than it was in the ISA era.

Linux: where IRQs are wonderfully visible

On Linux, interrupts are easier to observe. Tools and files like /proc/interrupts can show per-CPU interrupt counts, helping you spot

a device that’s generating a huge volume of interrupts or an imbalance where one CPU core is doing all the interrupt work.

Interrupt Storms: When the Doorbell Gets Stuck

An interrupt storm is what happens when interrupts arrive so frequently that the system spends too much time handling themand not enough time

doing useful work. This can happen due to:

- a buggy driver that “claims” interrupts incorrectly,

- a device that keeps asserting a level-triggered interrupt because it wasn’t properly acknowledged,

- misconfigured trigger mode or sharing between incompatible devices,

- hardware faults that cause repeated error interrupts.

In storms, the CPU can get stuck in a loop of “handle interrupt, return, handle interrupt again,” which feels like the system is frozen

because it’s too busy answering the door to do anything else.

Quick FAQ About IRQs

Do IRQ conflicts still happen?

True “IRQ conflicts” in the old-school sense are much rarer on modern systems because interrupt routing is more flexible and sharing is expected.

When problems occur today, they’re more commonly tied to driver behavior, firmware quirks, or device faults rather than a simple “two devices picked IRQ 5.”

Why do I see IRQ numbers higher than 15?

Because you’re living in the future (congrats). Modern interrupt controllers and MSI/MSI-X allow many more interrupt identifiers than classic PIC-era systems.

Higher numbers often reflect routed interrupts, per-queue interrupts (common on NICs), or modern APIC/IO-APIC mappings.

Can regular software trigger an IRQ?

Generally, noat least not directly. Hardware IRQs originate from devices, and the OS controls how interrupts are handled. Software can trigger exceptions,

system calls, and other control transfers that look “interrupt-like,” but direct hardware interrupt generation is typically privileged.

Conclusion: IRQs Are the Computer’s “Now, Please” Button

An interrupt request (IRQ) is a core mechanism that lets hardware (and sometimes system software) demand immediate CPU attention.

It’s how your computer stays responsive without wasting time constantly polling every device. The interrupt controller routes the request, the CPU runs a handler,

and the OS keeps the whole process from turning into chaos.

The best part? Most of the time, IRQs do their job quietly, like a well-run backstage crew. The worst part? When something goes wrong, they can be dramatically loud,

like a doorbell that’s stuck… and you live in a building with 5,000 roommates.

Real-World Experiences With IRQs (The “I Didn’t Know This Was a Thing” Edition)

If you’ve spent time building PCs, running servers, developing drivers, or tinkering with embedded boards, you’ve probably “met” IRQseven if you didn’t realize it.

Here are some common experiences people run into, written as realistic composites of the kinds of stories that show up in support threads, dev chats, and late-night

troubleshooting sessions.

1) “Why is my CPU at 30% when I’m doing nothing?”

A classic: the system is “idle,” but a single CPU core is strangely busy. Someone checks performance counters and notices a suspicious number of interrupts.

On Linux, /proc/interrupts reveals a device racking up counts at an alarming rateoften a network interface under noisy traffic, a misbehaving USB device,

or a driver stuck in a loop. The fix isn’t “turn off interrupts” (that’s like fixing a smoke alarm by removing the battery while the kitchen is on fire).

Instead, it usually involves updating a driver/firmware, adjusting how the device coalesces interrupts, or letting IRQ balancing distribute the load.

2) “My audio crackles when I download a big file”

This one feels unfair: why would networking mess with sound? Because interrupts and latency are roommates. Under heavy I/O, a system can experience bursts of interrupt

handlingnetwork packets arriving, storage completions, USB activity. If driver routines take too long or the system gets hammered with interrupts, time-sensitive audio

processing may miss its deadlines. People often describe this as pops, crackles, or stutters during downloads or game installs. The eventual solution can be as simple as a

driver update, or as annoying as tracking down one problematic device/driver path that’s causing latency spikes.

3) “Device Manager shows everything on the same IRQshould I be worried?”

Many Windows users eventually open Device Manager, see multiple devices “sharing” an IRQ, and assume the PC is about to explode.

In modern ACPI systems, sharing can be normalWindows and the firmware route interrupts through modern controllers so multiple devices can coexist.

The real test is behavior: if everything runs smoothly, it’s usually fine. If you’re seeing freezes, dropouts, or device resets, then the shared IRQ display becomes

a cluenot a verdict. In other words: sharing isn’t guilty until proven guilty.

4) “My embedded project worked… until I enabled one more interrupt”

Embedded developers learn IRQ humility quickly. You add a timer interrupt for scheduling, then add UART interrupts for serial I/O, then add a GPIO interrupt for a button,

and suddenly the system behaves like it drank three energy drinks. The culprit is often priority and timing: one ISR runs too long, starving another; an interrupt is triggered

faster than it’s cleared; or a critical section blocks interrupts longer than expected. The best embedded advice is painfully consistent:

keep ISRs short, acknowledge the source correctly, and defer heavier work outside the handler whenever possible.

5) “The mysterious ‘interrupt storm’ that turned a fast machine into a slow one”

Few phrases are more ominous than “interrupt storm.” People report a system that suddenly becomes unresponsive, fans spin up, and the mouse cursor moves like it’s wading

through peanut butter. In many cases, the underlying story involves a driver that repeatedly claims interrupts it didn’t cause, a misconfigured trigger mode, or a device

stuck asserting an interrupt because the acknowledgment path is broken. Debugging can feel like detective work: identify the noisy interrupt source, isolate the device,

and then decide whether the fix is driver, firmware, configuration, or hardware replacement.

The comforting takeaway: IRQs are not spooky magic. They’re a well-defined system for urgent attention. When you know what they are, “IRQ” stops being a mysterious acronym

and starts being what it really is: the computer’s very practical way of saying, “Pause everythingI have news.”