Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Versailles Made Privacy a Political Weapon

- “Toilette” Didn’t Mean Toilet (At First)

- So… Could You Really Pee in Front of the Queen?

- Where Did Everyone Actually Go?

- The Hidden Logic Behind “Bizarre” Manners

- Myths vs. Reality: What People Get Wrong About Versailles Bathrooms

- What This Says About Power (And Why We Still Care)

- Experience Add-On: Inside a Versailles Morning

- Conclusion

If you’ve ever felt awkward when someone knocks on the bathroom door, congratulations: you were not raised at Versailles.

In the French royal court (especially under Louis XIV and his successors), privacy wasn’t just “limited”it was practically

a luxury item you had to earn with titles, favors, and excellent posture.

That’s how we end up with the headline-friendly idea that you could “pee directly in front of the Queen.” It’s a spicy claim,

but like most spicy claims, it needs cooling down with context. The truth is both stranger and more interesting:

Versailles turned daily life into performance art, and “bathroom etiquette” sat right at the intersection of status,

technology, and a social system built on being seen.

Why Versailles Made Privacy a Political Weapon

Versailles wasn’t just a palace. It was a machine that converted attention into power. The king’s day was famously scheduled,

and major momentswaking, dressing, eating, worshipping, going to bedcould become formal rituals where access meant prestige.

If you were close enough to be present, you were close enough to matter.

The king’s morning: the “lever” and the crowd

The king’s getting-up ceremony (the lever) wasn’t a cute, intimate morning routine. It was structured, hierarchical,

anddepending on the periodcrowded. Court offices and social rank determined who could enter, who could assist, and who had

to wait outside like a human “seen” receipt. The point wasn’t comfort. The point was visibility: who got to witness the king

as a living, breathing source of rewards.

Etiquette wasn’t “nice manners”it was a ranking system

Modern manners are often about smoothing social friction. Court etiquette was about creating itand then selling the solution.

Tiny privileges were treated like gold: handing a garment, presenting an item, standing in a particular spot, speaking at a

particular moment. Every rule produced a social pecking order. Every pecking order produced competition. And competition kept

nobles busy with each other instead of busy with rebellion.

“Toilette” Didn’t Mean Toilet (At First)

Before we sprint into the restroom, we need to talk about language. In court life, “toilette” often meant grooming and

dressinga ritualized process of washing, styling hair, applying cosmetics, and putting on the day’s layers like you’re

prepping for a portrait that might also be a political crisis.

This matters because a lot of modern “Versailles was so gross” stories blur two separate realities:

the very public grooming rituals of royalty, and the very real sanitation problems of a huge residence filled with thousands

of people, servants, visitors, and constant motion.

So… Could You Really Pee in Front of the Queen?

Not as a formal, court-approved pastime, no. Nobody filed a petition for “Front-Row Queen Pee Privileges,” and the queen’s

public toilette was primarily about dressing and receiving people, not about bodily functions.

But the spirit of the claimthat privacy norms were wildly different, and that bodily needs collided with public lifeis

grounded in how the court operated. Here’s how “something like that” could happen.

1) The queen received guests during her toilette

The queen’s bedchamber was not just for sleeping. In the morning, she could receive visitors during and after her toilette,

and this could be regulated by strict etiquette. That means the queen could be surrounded by attendants and courtiers while

she was being prepared for the day. If you’re imagining a serene spa day with cucumber water, please replace that thought

with “a ceremonial dressing room where rank has better seating than comfort.”

2) Portable “urinals” existed for womenbecause fashion was basically architecture

Court clothing was not designed for convenience. Wide skirts, layers, and stiff structures created a practical problem:

how do you go, especially during long ceremonies, travel, or times when leaving would be socially complicated?

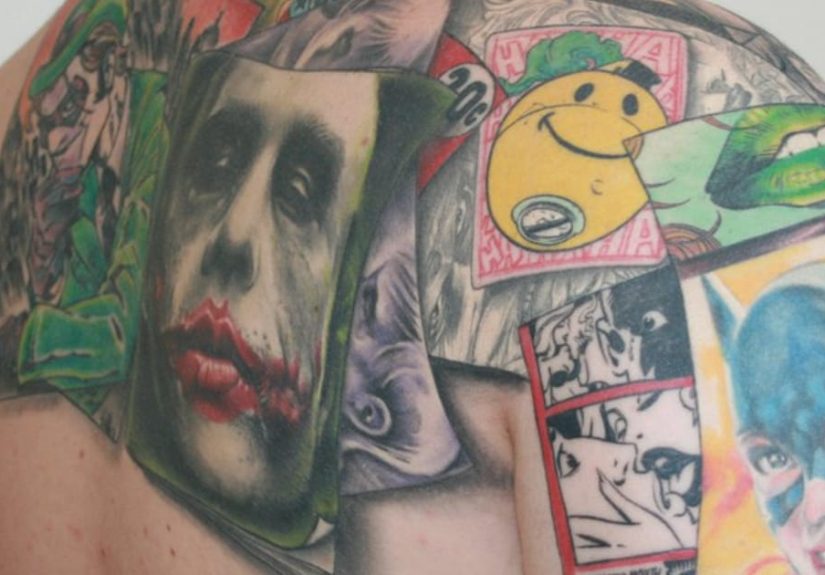

Enter the bourdaloue: a small, oval (often porcelain) chamber pot shaped for use without fully undressing. Museums preserve

these objects today, which is both fascinating and a little humbling (the past is glamorous until it’s ceramic bathroom tech).

The bourdaloue’s very existence tells you the obvious: women sometimes needed “solutions” that worked in a world where

disappearing for a restroom break could be difficult.

3) Versailles had sanitation challengesand desperation makes etiquette flexible

Versailles was enormous and crowded. Dedicated toilets existed, but not in a modern “every hallway has a restroom” sense.

Many people relied on chamber pots, commodes, and private arrangements. When a building hosts court life, politics, ceremonies,

and heavy foot traffic, you get bottlenecks, mess, and sometimes truly terrible ideas made in a hurry.

So while “peeing directly in front of the queen” is a sensational framing, the underlying reality is that the court’s public

nature and limited facilities could push bodily needs into semi-public spacesespecially for those who weren’t high-ranking

enough to access the best arrangements or leave at the ideal moment.

Where Did Everyone Actually Go?

Chamber pots and commodes: the invisible workforce of court life

The simplest answer is also the most common: chamber pots. Many rooms relied on a pot (or a commode chair concealing one),

and someoneusually a servanthandled the aftermath. This is the unglamorous engine behind glamorous living:

you can’t have a palace that runs like theater unless backstage is hauling props. Some of those props were, unfortunately,

full of yesterday.

Public latrines existed, but “public” didn’t mean pleasant

Latrines and shared facilities were part of palace life, but they weren’t always plentiful, well-placed, or well-managed.

Add crowds, rigid schedules, and people who believed “good breeding” outweighed “basic hygiene,” and you get conditions that

visitors sometimes described in disgust. Versailles could be breathtaking in gold and mirrorsand then aggressively

unromantic in the corners and corridors.

The royal paradox: luxury aesthetics, pre-modern plumbing

The court invested heavily in spectacle: architecture, art, fountains, clothing, and ritual. Plumbing, by comparison, was a

slower technological story. Some private spaces for elites included better amenities over time, and later renovations could

add more privacy (including specialized rooms and water-closet-style installations in private suites). But for much of the

palace’s most famous era, convenience did not scale as fast as grandeur.

The Hidden Logic Behind “Bizarre” Manners

Being watched was the point

If Versailles etiquette feels absurd, it’s because it was engineered for a purpose. Public rituals made the monarchy feel

constant, central, and unavoidable. You didn’t just obey the kingyou oriented your day around him. You didn’t just respect

rankyou performed it through micro-rules that trained everyone to think in hierarchies.

“Weird” etiquette created social gravity

The rules weren’t random. They concentrated attention around the royal body. They rewarded attendance. They encouraged nobles

to compete for proximity rather than organize power elsewhere. And they made status visible in a way that felt natural because

it was repeated daily, like a ritual you stop questioning because it’s always been there.

Myths vs. Reality: What People Get Wrong About Versailles Bathrooms

-

Myth: “Everyone constantly relieved themselves in the halls like it was normal.”

Reality: Some people did desperate or disgusting things, but that doesn’t mean it was the accepted standard.

Crowds + limited facilities can create incidents without creating “official manners.” -

Myth: “The queen’s toilette was literally a bathroom show.”

Reality: “Toilette” usually meant grooming and dressing, and the queen received visitors during and after it.

That’s publicbut not necessarily in the way modern readers first imagine. -

Myth: “The court was too fancy to have gross problems.”

Reality: Fancy and gross are not enemies. They can be roommates.

What This Says About Power (And Why We Still Care)

Versailles bathroom stories go viral because they compress a big idea into a shocking image: power can be so extreme that even

bodily functions become part of the social order. But the deeper lesson is that control isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s

quiet, ritualized, and dressed in velvet.

The court didn’t just govern with laws and armies. It governed with access, attention, and a never-ending performance of rank.

And once you see that, the “weird manners” stop looking like random weirdness and start looking like strategy.

Experience Add-On: Inside a Versailles Morning

Imagine you’re a minor noble at Versailles. Not “your portrait is in a museum” noblemore like “you have a title, a tight

budget, and a desperate need to be noticed” noble. You wake up early because everyone wakes up early, and because sleeping in

means missing the one thing that might change your life: being seen near the king.

You dress like you’re being paid per buckle. Your outfit is stunning, expensive, and designed with the emotional warmth of a

decorative suit of armor. You shuffle toward the royal apartments with the focused expression of a person who has rehearsed

bowing in a mirror. The hallway fills with people who look just as polished and just as anxious. You can almost hear

ambition creaking like the palace floors.

The king’s morning rituals begin. Doors open and close in stages. People enter by rank, as if the room itself has a bouncer.

Those closest to the action glow with the smug relief of winning a tiny lottery. Everyone else pretends they’re not jealous,

which is adorable. You wait. You watch. You laugh politely at jokes that are only funny if you own land.

And then your body betrays you. You drank something earliermaybe wine, maybe hot chocolate, maybe just the tears of your

enemiesand now you need a restroom. Immediately. You scan the scene the way modern people scan a crowded coffee shop for an

outlet. Where do you go? How do you leave without looking unimportant? How do you return without missing the moment when

someone influential glances in your direction?

If you’re powerful, you have options: private spaces, servants who handle logistics, rooms designed for your comfort. If you’re

not, your options shrink fast. You consider leaving and risk missing everything. You consider staying and risk humiliation.

You consider asking someone for directions and realize that “Where’s the bathroom?” is not the kind of sentence that improves

your social ranking.

Meanwhile, the queen’s morning is its own ritual. Her toilette is a courtly affair: attendants, visitors, layers of clothing,

and the invisible math of who stands where. You might not be anywhere near her, but you feel the same pressure: appear calm,

appear elegant, never appear human. Versailles rewards the performance, not the needs underneath it.

Eventually you find a solutionmaybe a discrete arrangement, maybe a servant’s whispered advice, maybe the period-accurate

equivalent of “good luck, buddy.” And when you return, you look composed. That’s the trick. At court, dignity isn’t the absence

of bodily reality. It’s the ability to pretend it doesn’t exist while everyone else pretends with you.

Conclusion

The French royal court didn’t officially invite people to urinate in front of the queen like it was a party game. But Versailles

absolutely did blur the boundaries between public and private in ways that feel shocking todaybecause visibility was currency,

etiquette was infrastructure, and pre-modern sanitation had to serve a modern-sized social machine.

So the next time you read a headline about “weird royal manners,” keep the best version of the story: not just the gross-out

detail, but the reason it existed. At Versailles, the real spectacle wasn’t the gold leaf. It was the way power got under

everyone’s skinsometimes before breakfast.