Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Happened in California, Exactly?

- Plague 101: The Bacterium, the Fleas, and the Very Uncool Name

- The Three Types of Plague (Because One Wasn’t Dramatic Enough)

- Is Plague Actually Dangerous Today?

- How to Lower Your Risk (Without Turning Into a Bubble-Wrapped Hermit)

- So Why Did Newton Think Toad Vomit Was a Good Idea?

- What the Newton Story Teaches Us (Besides “Do Not Eat Chimney Toads”)

- Common Myths That Make Plague Sound Scarier (or Weirder) Than It Is

- What to Watch For After Outdoor Exposure

- Real-World Experiences Related to the California Plague Headline (About )

- Conclusion: A Modern Case, an Old Manuscript, and a Very Clear Takeaway

If you had “plague” on your California bingo card, congratulations (and also… yikes). A recent human plague case

tied to the South Lake Tahoe area is a reminder that some ancient-sounding diseases never fully left the chat.

The good news: modern medicine is not powered by vibes, leeches, or amphibian puke. The bad news: fleas are still

out here freelancing.

And because the universe has a sense of comedic timing, this modern headline collided with a historical gem:

Isaac Newtonyes, that Newtononce noted a “cure” for plague involving powdered toad and toad vomit.

Which proves two things at once: (1) smart people can believe weird stuff, and (2) history would like a word with

your “natural remedies” group chat.

What Happened in California, Exactly?

The reported case involves a resident in the South Lake Tahoe area (El Dorado County) who tested positive for

plague. Officials believe the person likely became infected from a flea bite while spending time outdoors, and the

individual was reported to be recovering at home under medical care. Investigators also began looking into

potential exposure sites and local conditionsstandard public-health detective work when a rare infection shows up.

It’s worth emphasizing what local officials emphasized, too: human plague infections in California are rare, but the

bacterium that causes plague can still circulate among wild rodents in certain higher-elevation areas. Translation:

the disease isn’t “back” like a rebooted TV showit’s more like it never moved out, it just keeps a low profile.

Why Lake Tahoe and similar areas come up in plague stories

Plague is maintained in nature through a rodent-and-flea cycle. When plague activity increases in local rodent

populations, the odds rise that fleas will bite other animals (including pets) or people. That’s why health agencies

monitor rodents and fleas in specific regions and why advisories tend to pop up around the same kinds of landscapes:

rural and semi-rural areas, campgrounds, and places with lots of ground squirrels, chipmunks, and their tiny

hitchhiking fleas.

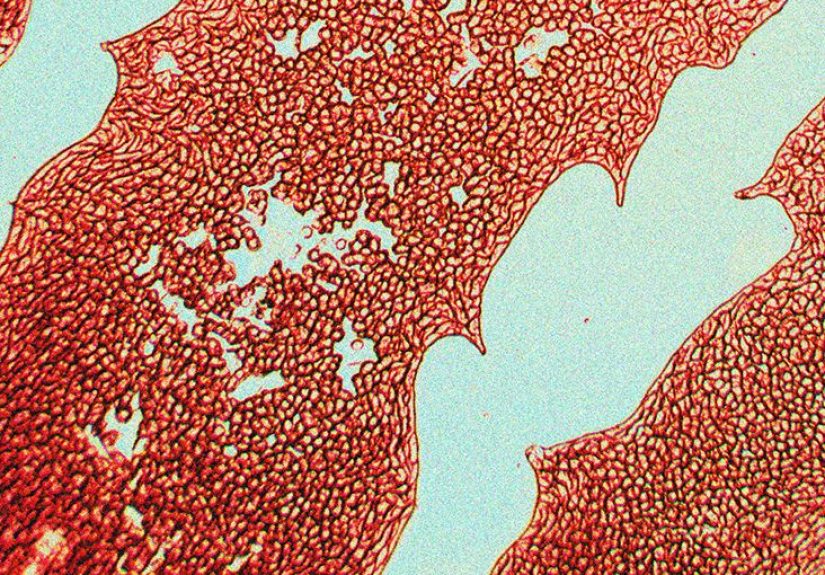

Plague 101: The Bacterium, the Fleas, and the Very Uncool Name

Plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis. Humans usually become infected in one of three

ways:

- Flea bites from fleas that fed on infected rodents.

- Handling infected animals (including sick or dead wildlife) or exposure to their tissues/fluids.

- Respiratory spread in rare cases of pneumonic plague (more on that in a minute).

“Plague” sounds medieval because it famously caused massive outbreaks in the past. But today, in the United States,

it’s typically a rare, sporadic illnessmore “unwelcome surprise” than “apocalypse.” When detected early, plague is

treatable with antibiotics.

The Three Types of Plague (Because One Wasn’t Dramatic Enough)

1) Bubonic plague

This is the most common form in naturally occurring U.S. cases. It typically follows a flea bite, and symptoms

often include fever, chills, weakness, headache, and the classic sign: a swollen, painful lymph node called a

bubo (commonly in the groin, armpit, or neck). The incubation period is often a few days after

exposureso it can feel like you caught a “camping bug” until the lymph node swelling makes it very clear you did

not.

2) Septicemic plague

This happens when the bacteria spread into the bloodstream. It can develop on its own or as a complication of

bubonic plague. Symptoms can include fever and weakness, plus signs of serious bloodstream infection. This is not a

“sleep it off” situation.

3) Pneumonic plague

This is the lung infection form and the most urgent from a public-health standpoint because it can spread from

person to person via respiratory droplets in certain circumstances. It can also develop if untreated plague spreads

to the lungs. Symptoms may include fever, cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. It’s rare, but it’s the form

that makes everyone say, “Okay, now I’m listening.”

Is Plague Actually Dangerous Today?

Yesand also, no, it’s not the 1300s.

Plague can be very serious if untreated. Historically it was devastating; clinically, it can still become severe

quickly. But in modern settings, with prompt diagnosis and appropriate antibiotics, many patients recover. That

“prompt” part is doing a lot of work here: waiting it out is how you turn a treatable infection into a bigger

problem.

How it’s treated now

Antibiotics are the standard of care. In the U.S., clinicians use specific antibiotic regimens (for example,

gentamicin and certain fluoroquinolones are commonly used first-line depending on the clinical situation). Treatment

approach and route (IV vs. oral) depend on severity and disease form, and clinicians move quickly when plague is

suspected.

If you’re thinking, “So… not toad vomit?” Correct. Enthusiastic correct.

How to Lower Your Risk (Without Turning Into a Bubble-Wrapped Hermit)

If you hike, camp, hunt, fish, or generally enjoy being outdoors where rodents live (which is… most outdoors),

you don’t need panic. You need good habits. Here’s what public health guidance tends to emphasize:

Outdoor and camping precautions

- Don’t feed wild rodents (yes, even if the chipmunk looks like it pays rent there).

-

Avoid contact with sick or dead animals. Don’t pick them up. Don’t “save” them barehanded.

Don’t let kids investigate with their fingers. - Don’t camp or rest near animal burrows or places where dead rodents are observed.

-

Use insect repellent and consider treating clothing/gear with permethrin where appropriate.

Flea bites commonly happen on lower legs and ankles, so socks and pant cuffs deserve the VIP treatment. - Watch for posted warnings in areas with known plague activity.

Pet precautions

Pets can bring fleas closer to you, and cats can become sick from plague after hunting rodents. Keep pets from

roaming in rodent-heavy areas, and talk with a veterinarian about effective flea controlespecially if you live in

or travel to regions where plague activity is known to occur.

So Why Did Newton Think Toad Vomit Was a Good Idea?

Let’s set the scene: 17th-century Europe. Plague outbreaks. Limited understanding of microbes. A medical landscape

where “theories” were sometimes indistinguishable from “things your cousin’s barber swears by.”

Isaac Newton, while brilliant, was also a person of his time. In notes he made while reading medical work about the

plague, Newton recorded a bizarre-sounding remedy involving a toad, its vomit, and a lozenge-like preparation worn

near the affected area. The idea was basically to “draw out” poison or contagionan older framework of disease that

didn’t involve bacteria because bacteria were not yet invited to the scientific meeting.

The “recipe” (historically interesting, medically useless)

Historical descriptions of Newton’s notes include hanging a toad for days until it vomits and dies, then combining

the toad material with the vomit to form lozenges. This was not Newton running clinical trials; it was Newton

collecting and synthesizing ideas from contemporary medical thinking. In other words, it’s an artifact of history,

not a suggestion for your pantry.

If you feel disappointed that Newton didn’t also recommend “drink water and get eight hours of sleep,” remember:

this was centuries before germ theory, antibiotics, and the concept of “maybe we don’t need to turn animals into

necklaces to fight disease.”

What the Newton Story Teaches Us (Besides “Do Not Eat Chimney Toads”)

1) Even geniuses are stuck with the tools of their era

Newton’s scientific legacy is enormous, but he lived in a world where the cause of plague wasn’t clearly understood.

When you don’t know what’s causing an illness, you’re more likely to accept explanations that fit the cultural

logic of the timemiasmas, poisons, “bad air,” and other invisible villains.

2) Plague shaped real history, including scientific history

Epidemics have a way of bending timelines. Plague outbreaks in the 1660s helped reshape daily life, institutions,

and the movement of people. Newton’s era included disruptions that influenced where people worked and studied.

That doesn’t mean plague “caused” genius, but it’s a reminder that public health and human progress are entangled

whether we like it or not.

3) Modern medicine is not perfect, but it is wildly better than toad-based fashion

When people say “we’ve forgotten how bad disease used to be,” they don’t mean “bring back the vomit lozenges.”

They mean: appreciate surveillance, diagnostics, antibiotics, and the boring-but-essential public health machinery

that helps keep rare diseases rare.

Common Myths That Make Plague Sound Scarier (or Weirder) Than It Is

Myth: “If there’s one case, there must be an outbreak.”

Not necessarily. Sporadic cases can occur when someone is exposed in a natural setting. Public health agencies take

them seriously, investigate exposure, and share guidance. Most people will never encounter plague in their lifetime.

Myth: “Plague is contagious like the flu.”

Bubonic plague is typically not spread person-to-person. Pneumonic plague can be, but it’s rare and requires close

contact under specific conditions. The most common story in the U.S. is still a flea bite or contact with infected

animals.

Myth: “Natural cures are safer.”

Nature made poison ivy, too. “Natural” does not mean “effective,” and it definitely doesn’t mean “safe.” Plague is

a serious bacterial infection; timely antibiotics are the proven approach.

What to Watch For After Outdoor Exposure

If you’ve been camping, hiking, or spending time in areas with wild rodents and you develop a sudden fever, feel

unusually ill, or notice a painful swollen lymph node, don’t self-diagnose via social media. Call a healthcare

professional and mention your recent outdoor exposure and location. Context helps clinicians consider less common

diagnoses.

This is not about being alarmist. It’s about being specific. “I feel awful” is a clue. “I feel awful and I was

camping near South Lake Tahoe and now my groin lymph node is the size of a walnut” is a much better clue.

Real-World Experiences Related to the California Plague Headline (About )

When public health officials say the risk to the general public is low, that doesn’t mean “nothing happened.”

It means the response is designed to keep it from turning into something bigger. People who work around these cases

often describe the same pattern: one surprising diagnosis, a fast chain of communication, and a lot of practical

prevention reminders that sound obviousuntil you realize how many of us do the opposite on vacation.

The “I thought it was just a rough camping trip” moment

A common experience reported in plague case write-ups is that the early symptoms can feel generic: fever, chills,

fatigue, maybe nauseaexactly the kind of misery you might blame on bad sleep, smoky campfires, or “that gas station

sandwich I shouldn’t have trusted.” People often don’t connect the dots until a swollen, painful lymph node shows up

or the fever refuses to budge. That’s when the story shifts from “I need electrolytes” to “I need a clinician.”

Inside the clinic: pattern recognition beats panic

Clinicians in the rural West talk about how exposure history is everything. When a patient mentions recent camping,

hiking, handling animals, or being around rodent burrowsand especially when there are swollen lymph nodesproviders

widen the diagnostic net. The experience is less “Hollywood quarantine scene” and more “smart questions, prompt

testing, and starting treatment quickly when suspicion is high.” In many cases, it’s the ordinary professionalism

that’s extraordinary: people doing the right thing fast, without turning the waiting room into a disaster movie.

The public health follow-up: the calm phone call you didn’t expect

After a rare diagnosis, patients often describe getting follow-up calls from public health staff who are polite,

direct, and very focused on details: Where were you camping? Did you notice rodents? Did your pet roam? Any flea

bites? Did you handle wildlife? This can feel strangelike you’re suddenly the main character in an epidemiology

podcastbut the goal is practical: understand likely exposure, assess whether anyone else might be at risk, and

decide whether local messaging or extra surveillance is needed.

Campground lessons people actually remember

Outdoor enthusiasts often share the same “I’ll never do that again” takeaways after hearing about plague activity in

a favorite area: don’t stash snacks near burrows, don’t let kids chase squirrels, don’t sit right next to

rodent holes because the view is nice, and don’t assume tiny bites on your ankles are always “just mosquitoes.”

People also get more serious about repellents and clothing choiceslong socks and tucked pants suddenly look less

like a fashion crime and more like a survival skill.

The pet angle: the quiet risk people forget

Many families say the biggest mindset shift is realizing pets can bring fleas closer to home. After a case makes

headlines, veterinarians often field questions about flea prevention, keeping cats indoors, and avoiding areas where

rodent activity is obvious. The experience tends to be grounding: you don’t need to fear the outdoors, but you do

need to respect the ecosystembecause the ecosystem does not care that your dog is “a good boy.”

Ultimately, the lived experience around a rare California plague case isn’t “constant fear.” It’s a short burst of

awareness, a reminder to take prevention seriously, and a quiet appreciation that antibiotics existbecause the

alternative, historically speaking, involved a chimney, a toad, and decisions nobody should make in this economy.

Conclusion: A Modern Case, an Old Manuscript, and a Very Clear Takeaway

The California plague case is a headline that grabs you by the collar, but the practical message is straightforward:

plague is rare, it can still occur in certain outdoor settings, and prompt medical care matters. Meanwhile, the

Newton-toad-vomit footnote is a hilarious (and horrifying) reminder that human beings have always tried to explain

disease with the best tools they hadwhether that was careful observation or… amphibian-based accessories.

If you take one thing from this: enjoy the outdoors, don’t feed the rodents, protect yourself from fleas, and when

you see a weird “cure” online, remember that even Isaac Newton once wrote something he probably wouldn’t retweet.