Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

If you’ve ever had a nosebleed that showed up at the worst possible momentjob interview, first date, wedding photosyou know how annoying they can be.

Now imagine nosebleeds that happen over and over again, not just once in a while, and sometimes come with serious internal bleeding you can’t even see.

That’s the reality for many people living with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, also known as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is rare, often misunderstood, and frequently underdiagnosed. Yet when it’s recognized early and monitored carefully, people can

live long, full lives. In this guide, we’ll walk through what causes the condition, the most common symptoms, and how doctors diagnose itso you can better

understand HHT and know what questions to ask if it affects you or someone you love.

What Is Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease?

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (OWR) is the older name for what doctors now usually call

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). It’s a

genetic blood vessel disorder passed down in families in an

autosomal dominant pattern. That means if a parent has HHT, each child has about a 50% chance of inheriting the condition.

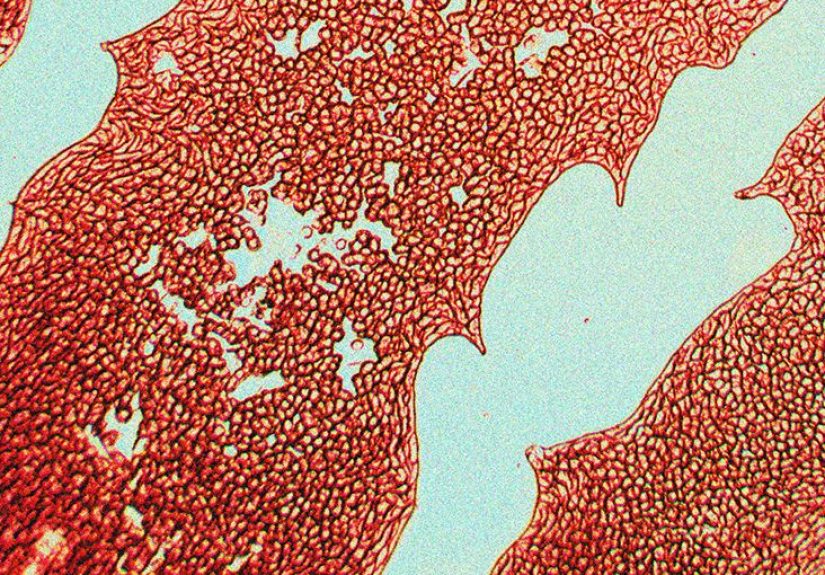

The hallmark of HHT is the development of abnormal blood vessels called

telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs).

Telangiectasias are tiny, dilated blood vessels near the surface of the skin or mucous membranes, while AVMs are larger, deeper abnormal connections between

an artery and a vein that bypass the normal capillary network. These fragile vessels can bleed easily and may interfere with normal blood flow and oxygen delivery.

HHT most commonly affects:

- The nose (leading to recurrent nosebleeds or epistaxis)

- The skin and mucous membranes (red or purple spots on lips, fingers, face, tongue)

- The lungs, brain, and liver (where larger AVMs can cause serious complications)

- The digestive tract (where bleeding may cause anemia)

Even within the same family, HHT can look very different. One person might have occasional nosebleeds and a few tiny skin spots, while another may have frequent

severe bleeding and AVMs that require intervention.

What Causes Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease?

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is caused by changes (mutations) in certain genes involved in building and maintaining blood vessels. The best-known

genes are:

- ENG (endoglin) – often referred to as HHT type 1

- ACVRL1 / ALK1 – associated with HHT type 2

- SMAD4 – linked to a combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and HHT

These genes provide instructions for proteins that help blood vessels grow and repair properly. When there’s a faulty gene, the resulting blood vessels can be

fragile, dilated, or improperly connected. Over time, this leads to telangiectasias on the skin and mucous membranes and AVMs in organs like the lungs, brain,

and liver.

Because HHT is inherited in an autosomal dominant way, it does not skip generations, but the signs can be subtle or appear later in life, so

it may seem like it skipped someone. A person can also be the first in the family to have a new mutation, but once they have it, it can be passed on to their

children.

Common Symptoms of Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease

You don’t have to have every symptom on the list to have Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. In fact, symptoms often evolve with age. The most typical signs and symptoms include:

1. Recurrent Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

Nosebleeds are the most common symptom of HHT. They often start in childhood or teenage years and may become more frequent over time. Some people bleed

once in a while; others have daily episodes that last several minutes or longer. Chronic nosebleeds can lead to iron-deficiency anemia, fatigue, and reduced quality of life.

Many people initially chalk up these nosebleeds to “dry air,” “allergies,” or “just my family’s thing.” When nosebleeds are frequent, spontaneous, and hard to

control, they are a key clue to Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

2. Telangiectasias on the Skin and Mucous Membranes

Telangiectasias often appear as small, flat or slightly raised red or purple spots. They may show up on:

- Lips and around the mouth

- Tip of the tongue and inside the cheeks

- Face, especially sun-exposed areas

- Fingertips and hands

These tiny vessels can bleed with minor traumathink brushing your teeth, eating chips, or bumping your hand. Some people worry they’re “broken capillaries” or

cosmetic blemishes, but in the context of frequent nosebleeds or a family history of HHT, they’re an important diagnostic sign.

3. Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding

Telangiectasias can also form throughout the digestive tract, especially in the stomach and small intestine. Bleeding here is often slow and hidden, so you might not

see red blood or black stool. Instead, people notice:

- Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

- Fatigue, shortness of breath, or dizziness

- Occasional dark stools or visible blood in stool in more significant bleeding

GI bleeding from HHT tends to show up later in adulthood and may require iron supplements, IV iron, or sometimes blood transfusions.

4. Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs) in Major Organs

Larger AVMs are a big part of why early diagnosis and screening in HHT are so important. These abnormal connections can form in:

- Lungs – Lung (pulmonary) AVMs can allow blood clots or bacteria to bypass the filtering capillaries and go straight to the brain, raising the risk of stroke or brain abscess. They can also cause shortness of breath, fatigue, and low oxygen levels.

- Brain – Brain AVMs may be silent or cause headaches, seizures, or neurological symptoms. Rarely, they can bleed, leading to a hemorrhagic stroke.

- Liver – Liver AVMs can alter blood flow through the liver and strain the heart. Some people develop high-output heart failure or liver problems over time.

Many AVMs cause no symptoms at all until they’re found on imaging. That’s why screening is crucial once HHT is suspected or confirmed.

5. Anemia and Fatigue

Chronic bleedingfrom nose, GI tract, or bothcan slowly deplete iron stores. People with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease frequently experience:

- Tiredness that doesn’t match their activity level

- Shortness of breath, especially with exertion

- Headaches or feeling “foggy”

- Pale skin or cold hands and feet

Iron-deficiency anemia is often one of the first measurable consequences of HHT and may be the reason someone gets evaluated in the first place.

How Is Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease Diagnosed?

Diagnosing Osler-Weber-Rendu disease isn’t based on a single blood test. Instead, doctors use a combination of clinical clues and, when possible, genetic testing.

The standard clinical tool is a set of guidelines known as the Curaçao criteria.

The Curaçao Diagnostic Criteria

According to the Curaçao criteria, HHT is considered:

- Definite if you meet 3 or more criteria

- Possible or suspected if you meet 2 criteria

- Unlikely if you meet fewer than 2 criteria

The four Curaçao criteria are:

- Spontaneous and recurrent nosebleeds (epistaxis)

- Multiple telangiectasias at characteristic sites (lips, oral cavity, fingers, nose)

- Visceral lesions such as AVMs in the lungs, brain, liver, or telangiectasias in the GI tract

- First-degree relative with HHT (parent, sibling, or child) under these same criteria

These criteria help clinicians make a diagnosis even before genetic testing is available or completed, which is particularly important in countries or settings where

genetic testing is expensive or limited.

Physical Exam and Medical History

Your healthcare provider will typically start with a detailed history and physical exam, asking about:

- How often you get nosebleeds, how long they last, and what triggers them

- Any history of anemia, iron supplements, or blood transfusions

- Neurological symptoms like seizures, strokes, or severe headaches

- Shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, or unexplained fatigue

- Family members with similar symptoms or a known HHT diagnosis

They’ll also carefully examine your skin, lips, mouth, and fingers looking for telangiectasias. Those tiny red or purple spots often tell a big story.

Imaging Studies for AVMs

Because AVMs can quietly cause serious complications, screening is a key part of evaluating someone with confirmed or suspected HHT. Common tests include:

- Contrast echocardiogram (“bubble study”) to look for abnormal blood flow from the right to left side of the heart that suggests lung AVMs.

- CT scan of the chest (often with contrast) to visualize pulmonary AVMs in more detail.

- MRI of the brain to check for brain AVMs, especially in children and young adults with HHT.

- Ultrasound or other imaging of the liver if liver AVMs are suspected.

Not everyone needs every test immediately. Screening is usually guided by age, symptoms, and family history, often following specialized HHT center guidelines.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing can help confirm Osler-Weber-Rendu disease and identify which gene is affected. This information can:

- Confirm the diagnosis in someone with borderline clinical features

- Help test at-risk relativeseven before symptoms appear

- Guide screening and follow-up plans

A negative genetic test doesn’t completely rule out HHT, because not all possible HHT-causing genetic changes are known. In those cases, doctors rely even more

heavily on the Curaçao criteria and clinical judgment.

When Should You See a Doctor?

Recurrent nosebleeds and a few red spots on the lips do not automatically mean you have Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. But you should talk with a healthcare professionalpreferably one familiar with HHT or a related field like hematology or geneticsif you notice:

- Frequent nosebleeds, especially if they started at a young age

- Multiple telangiectasias on your lips, tongue, fingers, or inside your mouth

- Unexplained iron-deficiency anemia or chronic fatigue

- A history of stroke, brain abscess, or severe shortness of breath at a young age

- A parent, sibling, or child with diagnosed HHT

Early diagnosis allows for targeted screening for AVMs and proactive treatment of bleeding and anemia. It can also help family members get evaluated

before serious problems occur.

Living with Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease

While Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is lifelong, it is not hopeless. Many people with HHT hold jobs, raise families, travel, and live very normal-seeming liveswith a bit of extra planning.

Management may include:

- Control of nosebleeds with humidification, nasal ointments, cauterization, or more advanced local treatments when needed

- Monitoring and treating anemia through diet, oral iron, IV iron infusions, or transfusions when necessary

- Intervention for AVMs in the lungs or brain through procedures like embolization or surgery, when indicated

- Regular follow-up with a team experienced in HHToften at a dedicated HHT center

Lifestyle adjustments can also make day-to-day life easier: using a humidifier, limiting medications that increase bleeding risk, staying on top of

iron levels, and knowing when to seek urgent care. Education and supportfrom specialists, patient organizations, and others living with HHTcan make a huge difference.

Real-Life Experiences with Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease

Facts and criteria are helpful, but they don’t fully capture what Osler-Weber-Rendu disease feels like in real life. While every person’s story is different,

a few common experiences tend to show up again and again. The examples below are composites based on typical patient journeys and are meant to illustrate

what living with HHT can look like.

“I Thought It Was Just a Family Nosebleed Curse”

Emma grew up believing nosebleeds were simply part of her family’s DNA. Her dad kept tissues in every room, and she learned early on to tilt her head forward,

pinch her nose, and wait it out. In middle school, she’d occasionally have to run out of class with blood suddenly pouring from her nose. Embarrassing?

Absolutely. Concerning? Not reallyat least, that’s what everyone assumed.

It wasn’t until her mid-20s, when Emma started feeling exhausted all the time, that a routine blood test showed significant iron-deficiency anemia. Her doctor

initially blamed her heavy periods, but extra iron pills didn’t fix the problem. When a new primary care provider asked about her lifelong nosebleeds and

noticed tiny red spots on her lips and fingers, the puzzle pieces finally clicked. Further evaluation led to a diagnosis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Looking back, Emma says the label “HHT” was scary at firstbut it was also a relief. Suddenly, the “family nosebleed curse” had a name, and more importantly,

a plan. She got screened for lung and brain AVMs, started regular iron monitoring, and learned practical tricks for managing nosebleeds. Her father, who had

always shrugged off his own symptoms, was later diagnosed as well and screened for AVMs. For their family, knowledge changed everything.

Silent AVMs and a Big Wake-Up Call

Daniel was a runner in his 30s who prided himself on being “that cardio guy” in his friend group. He had mild nosebleeds once or twice a month and a couple of

red spots on his lips, but nothing that got in the way of his daily life. One weekend, he developed a sudden, severe headache and weakness on one side of his body.

Emergency imaging revealed a brain AVM that had bled.

During hospitalization, his medical team noticed he also had a history of nosebleeds and telangiectasias. That led to genetic testing and screening of his lungs,

where they found pulmonary AVMs as well. Daniel later learned that his mother had similar nosebleeds but had never been evaluated for a genetic condition.

For Daniel, the experience was a frightening wake-up call but also a turning point. After treatment for his brain AVM and embolization of lung AVMs, he now

works closely with an HHT center, keeps up with regular screening, and has encouraged relatives to get evaluated. He jokes that nobody likes extra medical

appointments, but the trade-offdramatically lower risk of another strokefeels worth it.

Living with “Invisible” Bleeding and Daily Fatigue

Not everyone with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease has dramatic nosebleeds or strokes. For some, the main challenge is slow, internal bleeding and relentless fatigue.

Maria, in her 50s, spent years being told she was “just tired” from work and stress. She had mild nosebleeds but nothing dramatic. Her main complaints were

exhaustion, shortness of breath on stairs, and feeling like she could never catch up on sleep.

When she finally saw a hematologist, bloodwork showed significant anemia and low iron stores. Endoscopy revealed telangiectasias in her stomach and small intestine

tiny, slow-bleeding lesions that had never caused obvious “blood in the stool,” but had silently drained her iron over time. With iron infusions, treatment of

GI bleeding, and screening for AVMs elsewhere, her energy level gradually improved.

Maria describes her experience with HHT as “learning a new language” about her own body. She now knows that when she starts to feel unusually winded or foggy,

it can be a clue that her iron is dropping and she needs labs or follow-up care. She also shares her story with others in support groups, reminding them that

you don’t have to see blood pouring out to be losing blood.

Finding Support and Building a Care Team

One of the biggest themes among people with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is the importance of a knowledgeable care team and community. Because HHT is rare,

local providers may not see many cases in their practice. Patients often benefit from:

- Being seen ator at least consulting witha dedicated HHT center or specialist familiar with current guidelines

- Connecting with patient organizations for education and emotional support

- Bringing a written summary of their condition and medications to every medical or dental appointment

- Encouraging relatives with similar symptoms to get evaluated

While the idea of a genetic vascular disorder might sound intimidating, many people with HHT emphasize that information, screening, and planning turn fear into

proactive action. The more they understand their disease, the more they feel in control of their healthand less defined by nosebleeds, AVMs, or lab results.

Bottom Line

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, is a rare inherited vascular disorder that can range from mild, mostly cosmetic

symptoms to potentially life-threatening complications. Its key featuresrecurrent nosebleeds, telangiectasias, AVMs, and a positive family historyform the basis of

the Curaçao criteria used for diagnosis.

If you or a family member have frequent nosebleeds, visible tiny blood vessels on the lips or fingers, unexplained anemia, or a known family history of HHT,

talking with a healthcare professional is an important next step. Early diagnosis and regular screening for AVMs can dramatically reduce the risk of serious

complications and give you a clear roadmap for living well with this condition.

This article is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for personal medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider for questions about

diagnosis, treatment, or genetic testing for Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

SEO JSON