Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Pause and get medical help if any of this is happening

- Step 1: Wash your hands and set up a “clean zone”

- Step 2: Do a quick drainage check (color, amount, smell, and changes)

- Step 3: Remove the old dressing gently (no ripping, no heroics)

- Step 4: Clean the wound with water or salineskip the harsh stuff

- Step 5: Pat dry and protect the skin around the wound

- Step 6: Choose the right dressing for the amount of drainage

- Step 7: Apply the new dressing and secure itsnug, not tourniquet

- Step 8: Support healing with the “boring stuff” that actually works

- Step 9: Monitor dailyand know when it’s time to call a professional

- Common questions (because everyone asks them)

- Real-world experiences (what people commonly run into) 500-ish words

- Bottom line

A wound that’s “draining” can look scarybut it’s not automatically a disaster movie. Many healing wounds release fluid

(called drainage or exudate) as your body cleans up the area and rebuilds tissue. The goal isn’t to stop

every drop. The goal is to keep the wound clean, protect the skin around it, manage moisture, and spot trouble early.

This guide walks you through nine practical, real-life steps for draining wound care at home (the safe, common-sense kind).

It’s written for everyday situations like a cut that keeps oozing, a scraped knee that won’t quit, or a post-procedure incision

your clinician said to monitor. If your provider gave you specific instructions, those always win.

Step 1: Wash your hands and set up a “clean zone”

Wound care is mostly a germ-management sport. Start by washing your hands thoroughly with soap and warm water. If you have

disposable gloves, use themespecially if the wound is actively draining. Pick a clean surface, lay down clean paper towels,

and gather supplies before you touch the wound (because “one-handed scavenger hunt” is not a medical technique).

Helpful supplies

- Clean water or sterile saline (if you have it)

- Mild soap

- Non-stick dressing (often labeled “non-adherent”) and gauze/ABD pads for absorbency

- Medical tape or wrap (not too tight)

- Small trash bag for old dressings

- Petroleum jelly (for many minor skin wounds) or a skin barrier product if recommended

Step 2: Do a quick drainage check (color, amount, smell, and changes)

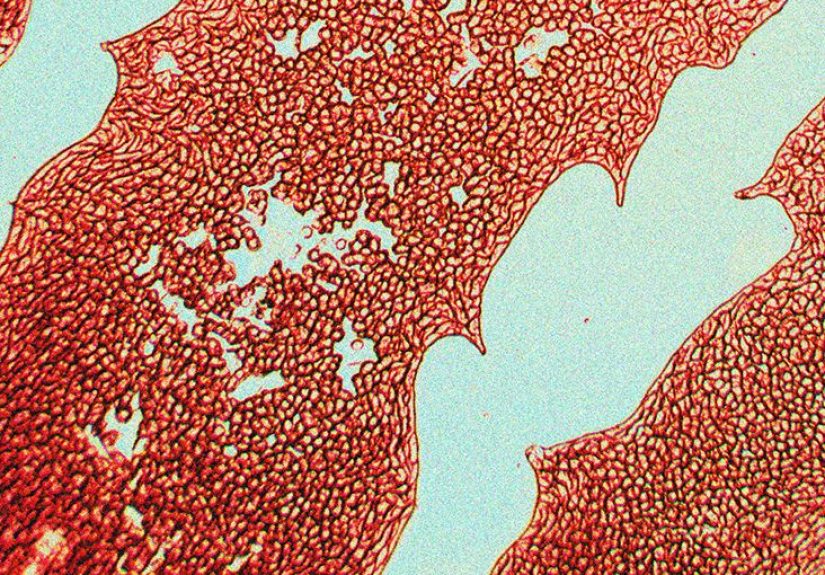

Before you clean anything, take 10 seconds to observe the drainage. This is your clue about what’s going on.

Many healing wounds drain a small amount of clear, pale yellow, or pink-tinged fluid. That can be normal. What’s more concerning is

drainage that becomes thick, cloudy, green/yellow, or bad-smellingor drainage that increases sharply after it had been slowing down.

A simple way to “log” drainage without turning into a scientist

- Color: clear/yellowish, pink, bright red, cloudy, green/yellow

- Amount: a few spots on the dressing vs. soaking through quickly

- Smell: none/mild vs. strong or foul

- Trend: better, same, or worse over 24–48 hours

If you’re caring for a surgical incision or a drain, many clinicians recommend tracking changes and contacting them if the

color/smell/amount suddenly shifts. When in doubt, take a photo for comparison (for your own tracking, not for a glamour shoot).

Step 3: Remove the old dressing gently (no ripping, no heroics)

Wash hands again (yes, again). Carefully peel off tape and remove the old dressing. If it sticks, don’t yankmoisten it with warm water

to loosen it, then lift slowly. Put the used dressing and gloves into a plastic bag, tie it off, and toss it.

If the wound is packed or you were told to do wet-to-dry dressings

Only do packing or wet-to-dry changes if a healthcare professional specifically instructed you. Follow their steps closely and keep your

follow-up appointmentsthese wounds often need rechecks, especially if drainage persists.

Step 4: Clean the wound with water or salineskip the harsh stuff

For many draining wounds, gentle cleaning is the sweet spot: enough to remove debris and old drainage, not so aggressive that you irritate

healing tissue. Rinse the wound with clean running water or sterile saline if you have it. Use mild soap on the surrounding skin, but try

not to scrub inside the wound.

A big myth to retire

Hydrogen peroxide and iodine aren’t great daily “healing helpers” for most routine wound care. They can irritate tissue and may slow healing.

Unless your clinician told you to use a specific antiseptic, stick with gentle rinsing and mild soap around the area.

If you see dirt or grit you can’t rinse away, don’t dig around with random objects. If needed, use clean tweezers (cleaned as directed),

and if you still can’t remove debris, get medical help.

Step 5: Pat dry and protect the skin around the wound

Drainage can be rough on the surrounding skin. Too much moisture can cause the edges to look white, soggy, or wrinkledthis is called

maceration, and it can make healing harder. After cleaning, gently pat the area dry with clean gauze.

Protect the “periwound” skin

- For many minor wounds, a thin layer of petroleum jelly can help keep the wound surface from drying out.

- If drainage is heavy, ask your clinician about a skin barrier product to protect the surrounding skin.

- Avoid tight, sticky tape directly on irritated skin when possibleconsider gentler options or wraps.

Step 6: Choose the right dressing for the amount of drainage

Dressings aren’t one-size-fits-all. The best dressing is the one that keeps the wound comfortably moist while absorbing extra drainage and

protecting the area from friction and germs.

Match the dressing to the situation

- Light drainage: non-stick pad + light gauze or a simple bandage.

- Moderate drainage: non-stick layer + gauze pad(s) that can absorb more.

- Heavy drainage: an ABD pad (more absorbent) over a non-stick layer; change as needed to prevent soaking through.

If the wound is surgical or you have special materials (steri-strips, skin glue, a drain site dressing), follow the instructions you were given.

Using the wrong product can pull at healing skin or trap too much moisture.

Step 7: Apply the new dressing and secure itsnug, not tourniquet

Place the clean dressing over the wound without touching the part that sits directly on the wound (handle the edges). Secure with tape or a wrap.

The goal is to keep it in place and protectednot to mummify the limb. Wrapping too tightly can reduce blood flow, which slows healing.

How often should you change it?

A common rule: change dressings at least daily or anytime they become wet, dirty, or loose. Draining wounds may need more frequent changes

at first. If you’re changing it constantly because it’s soaking through, that’s a sign you may need a more absorbent dressingor medical advice.

Step 8: Support healing with the “boring stuff” that actually works

Wounds heal best when your whole body is on the same team. That means good nutrition, hydration, and reducing stress on the area.

If you’re thinking, “That sounds too simple,” congratulationsyou’ve just discovered how often simple things matter.

- Eat protein regularly (your body needs building blocks).

- Stay hydrated unless your clinician told you to restrict fluids.

- Don’t smoke (smoking can slow wound healing).

- Manage blood sugar if you have diabeteshigh glucose can impair healing and raise infection risk.

- Reduce pressure and friction: cover the wound, pad if needed, and avoid rubbing clothes/shoes.

- Elevate if swelling is an issue (especially lower-leg wounds), if your clinician says it’s appropriate.

Step 9: Monitor dailyand know when it’s time to call a professional

The “trend line” matters. A healing wound usually becomes less painful, less red, and less leaky over time. If drainage is increasing, the wound looks

angrier, or you notice fever, foul smell, pus-like fluid, spreading warmth, or red streaks, get medical care promptly.

Also call if:

- The wound isn’t improving after a few days, or it’s worsening at any point.

- You have a chronic wound (or risk factors like diabetes/poor circulation) and healing stalls.

- The wound opens, stitches loosen, or bleeding soaks through the dressing.

- You were given a surgical drain and the output/appearance changes suddenly or the tube site becomes very red or tender.

Common questions (because everyone asks them)

Should I “let it air out”?

For many everyday wounds, keeping it clean, protected, and appropriately moist helps healing. “Open to air” can dry the surface, increase friction, and invite debris.

There are exceptionsso if your clinician told you to leave it uncovered at certain times, follow that plan.

Can I shower?

Many minor wounds can be gently rinsed in the shower, then re-dressed afterward. But surgical wounds and special dressings can have different rules.

If you’re post-op, follow the instructions you were given.

Do I need antibiotic ointment?

For many small cuts and scrapes, petroleum jelly is often enough to keep the wound moist. Some people use over-the-counter antibiotic ointment,

but it can irritate skin in some cases. If a clinician recommended it for your specific wound, follow their advice.

Real-world experiences (what people commonly run into) 500-ish words

Let’s talk about what this looks like in real life, because “change the dressing” sounds neat and tidy until you’re standing in the bathroom

holding a roll of tape that has decided to become a modern art sculpture.

Scenario 1: The post-procedure incision that’s leaking a little. A very common experience is noticing a small amount of clear, yellow,

or pink-tinged fluid on a dressing after a minor procedure. People often panic because “fluid” feels like “infection.”

But clinicians frequently explain that a little light drainage can be normal early on. What helps most is keeping it clean, changing the dressing

when it gets wet, and tracking whether the amount is trending down. The moment it becomes cloudy, foul-smelling, or paired with increasing pain

or fever, that’s when people are glad they called the surgical team sooner rather than later.

Scenario 2: The scraped knee that keeps oozing because life involves pants. A scrape on a joint (knee, elbow) can drain longer

simply because it keeps bending and rubbing. Many people find that the wound looks worse after sports, a long walk, or a day of tight jeans.

The “fix” is annoyingly practical: use a non-stick layer, add enough absorbency, and secure it so it stays put without strangling circulation.

People are often surprised by how much better a wound behaves when it’s protected from friction.

Scenario 3: The “I used hydrogen peroxide and now it’s angry” moment. Plenty of people reach for peroxide because it bubbles and

feels like it’s “doing something.” The common report: it stings, the skin gets irritated, and the wound looks raw. Switching to gentle rinsing with

water/saline and mild soap on the surrounding skinplus a simple protective dressingoften makes the area calmer within a day or two.

The big lesson: more sting doesn’t equal more healing.

Scenario 4: The wound that soaks through every bandage in an hour. This is when people realize they need a better plan (or a clinician).

Sometimes it’s as simple as using a more absorbent pad. Other times, heavy drainage is the body waving a little red flag: swelling, infection, poor circulation,

or a wound that needs professional evaluation. People who do best usually stop “winging it,” start tracking the drainage, and contact a provider with clear info:

how long it’s been draining, how fast it soaks dressings, and what it looks/smells like.

Scenario 5: The “I feel silly calling” situation. Many people hesitate to call because they think they’re overreacting.

But healthcare teams would rather answer a quick question than treat a bigger infection later. If the wound is getting more painful, more swollen, more smelly,

or you’re feeling unwellcalling is the smart move, not the dramatic one.

Bottom line

Treating a draining wound is mostly about consistency: clean hands, gentle cleaning, the right dressing, and daily monitoring.

Drainage can be normalbut changing drainage can be important. When the wound’s story doesn’t match “healing,” get a professional to read the next chapter with you.