Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why This Movie Still Gets Ranked (And Rewatched) Decades Later

- Quick Refresher: The Setup Without the Spoiler-Heavy Surgery

- Ranking #1: The Best Cons in the Movie

- Ranking #2: Best Performances and Character Value

- Ranking #3: Funniest Scenes (And Why They Work)

- Opinions: What Aged Like Fine Wine (And What Didn’t)

- Legacy: Why It Keeps Showing Up in Pop Culture

- Practical Watch Guide: How to Enjoy It Like a Pro (Without Getting Scammed)

- So, Where Does It Rank Among Classic Comedies?

- Viewer Experiences: The 500-Word Add-On (Because This Movie Lives in People’s Heads Rent-Free)

Some comedies make you laugh once, then politely fade into the “I liked it, I think?” section of your brain. And then there’s Dirty Rotten Scoundrelsa movie that

refuses to leave, because it keeps showing up in real life whenever someone says “trust me” a little too confidently.

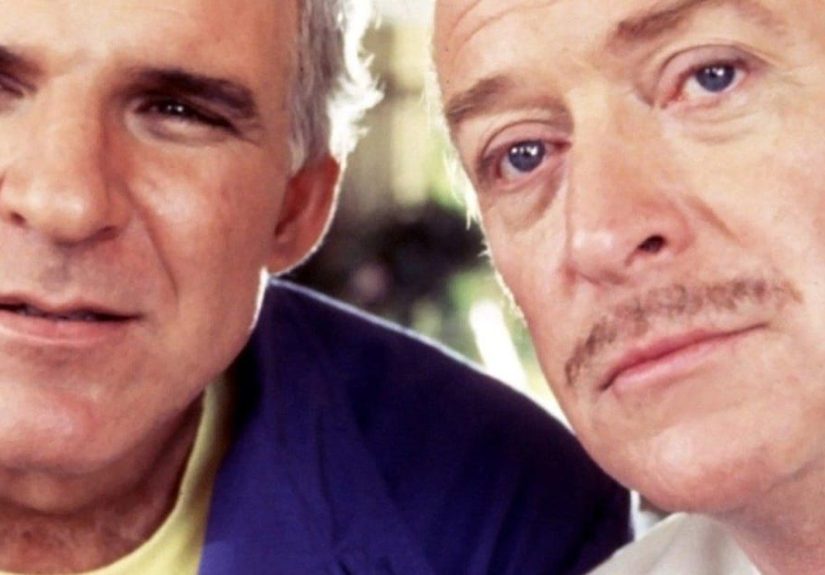

Released in 1988, directed by Frank Oz, and powered by the wildly mismatched duo of Michael Caine and Steve Martin, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels is a con-artist comedy set

on the French Riviera where charm is currency and everyone is one suitcase away from being emotionally pickpocketed. It’s slick, mean (but not cruel), and surprisingly

rewatchablelike a magic trick where you know you’re being fooled and you still clap like a seal because it’s done so well.

Why This Movie Still Gets Ranked (And Rewatched) Decades Later

The premise is simple enough to explain at a party: two con men fight over the same territory and bet on who can swindle a target out of $50,000. The execution, however, is

where the film becomes ranking material. It’s a comedy built on contrast: high-society finesse vs. low-rent hustle, elegant lies vs. desperate improvisation, and the kind of

confidence that comes from wearing a linen suit in public without fear.

Michael Caine plays Lawrence Jamieson like a man who could talk a lighthouse into buying sunglasses. Steve Martin plays Freddy Benson like a guy who would sell you those sunglasses,

then convince you they were cursed, then offer to “help” for $20. Their rivalry doesn’t just create jokesit creates a whole ranking ecosystem:

best cons, best scenes, best lines, best payoffs, best “wait…what?” moments.

Quick Refresher: The Setup Without the Spoiler-Heavy Surgery

Lawrence is an established “gentleman thief” working wealthy tourists on the Riviera. Freddy arrives as a chaotic disruptoran American grifter with the subtlety of a car alarm.

They collide, spar, and eventually make a wager centered on a new arrival: Janet Colgate, who appears sweet, wealthy, and (most importantly to them) convincingly bankable.

From there, the movie becomes a chess match played with fake accents, fabricated backstories, and increasingly ridiculous performances. It’s a battle of methods:

the refined con that looks like romance and philanthropy, versus the messy con that looks like desperation…because sometimes desperation is persuasive.

Ranking #1: The Best Cons in the Movie

Ranking cons is like ranking potato chips: it’s subjective, emotional, and someone will always argue that your #5 should be your #1. Still, here’s a strong, defensible list based

on creativity, execution, and payoff.

1) The “Ruprecht” Performance Con

This one wins because it’s a con inside a con. It turns acting itself into the weapon: a character so exaggerated it becomes unforgettable, yet still believable to the

target because the setup is emotionally manipulative and socially awkward in the exact way people tend to “politely accept.” It’s also where the movie’s physical comedy peaks.

2) The Psychiatrist / “Treatment” Con

Turning a medical authority figure into a prop is diabolical in the best comedic sense. It weaponizes expertise and trust, and the “treatment” sequences are both a running gag and

a pressure cooker for the rivalry. It’s not just “steal money” cleverit’s “make the other guy suffer while I do it” clever.

3) The Prince-and-Charity Routine

Lawrence’s signature scam is a master class in upscale persuasion: a fabricated identity, a noble cause, and the seductive idea that giving money makes you a better person

(and maybe a little irresistible). As a con, it’s elegant; as satire, it’s sharp.

4) The “Small-Time Hustler” Sympathy Pitch

Freddy’s approach is the opposite: fewer chandeliers, more guilt. His stories are built to trigger quick empathy and faster decisions. It’s not pretty, but it’s effectiveand the

film is smart enough to show why low-polish can still close the deal.

5) The Rivalry-as-Misdirection Strategy

This is the meta-con: while they’re focused on beating each other, the audience gets trained to watch them like they’re the only players. That assumption becomes a narrative trap

the film can spring later. It’s not a single trickit’s the movie’s entire engine.

6) The “Territory” Con (Social Control)

Lawrence maintains dominance not just through scams, but through relationships, reputation, and local systems that quietly protect him. It’s a reminder that real con artistry often

includes infrastructurealliances, favors, and people who look away at the right time.

7) The Final Turn (No Details, Just Respect)

The movie earns its ending because it doesn’t just twistit recontextualizes. A good con reveal makes you feel foolish. A great one makes you feel delighted that you got fooled.

This film aims for the second.

Ranking #2: Best Performances and Character Value

Not all characters are created equal; some exist to move plot, others exist to light it on fire. Here’s a ranking based on impact, comedy mileage, and how essential each role is to

the film’s tone.

1) Steve Martin as Freddy Benson

Martin’s genius here is his willingness to commit. Freddy isn’t “cool.” He’s needy, cocky, sloppy, and occasionally patheticyet never annoying long enough to lose the audience.

That’s a tightrope. His physical comedy and shamelessness are the film’s gasoline.

2) Michael Caine as Lawrence Jamieson

Caine plays Lawrence with restrained precision, and that restraint is what makes the absurdity around him funnier. He’s the straight man who is also a liar, which creates a great

tension: even his “honesty” feels like a performance. His charm is the film’s foundation.

3) Glenne Headly as Janet Colgate

Headly has the hardest job: playing sincerity in a movie about deception. If Janet feels flat, the movie becomes two men doing bits at each other. Instead, she brings warmth and

credibility, which raises the stakes and sharpens the satire.

4) Ian McDiarmid as Arthur

The dry, efficient assistant character is a classic comedy device, and the performance leans into quiet reactions and controlled exasperation. Arthur’s presence makes Lawrence’s

world feel organizedso Freddy’s chaos hits harder.

5) Supporting Players as Social Texture

The film uses supporting roles to sell the Riviera “ecosystem”: authority figures, tourists, and locals who either enable the scams or become collateral damage. They’re not all

equally memorable, but they keep the world from feeling like a stage set.

Ranking #3: Funniest Scenes (And Why They Work)

Comedy rankings always reveal more about the audience than the movie. Some people laugh hardest at wordplay, others at humiliation, others at pure physical absurdity. Dirty Rotten

Scoundrels wins because it offers all threeoften in the same scene.

1) The “Polite Setup, Wild Payoff” Moments

The film repeatedly builds calm, formal social situationsthen drops a comedic anvil. That contrast is key. When everything looks refined, even a small disruption becomes huge.

2) Scenes Where Lawrence Tries to Maintain Dignity

Watching an elegant con man forced into ridiculous circumstances is inherently funny because it attacks his identity. Lawrence isn’t just losing a contest; he’s losing the very

image he sells.

3) Scenes Where Freddy Overcommits

Freddy’s comedy comes from escalation. He doesn’t take a small lie and keep it tidyhe feeds it after midnight, gets it wet, and then introduces it to strangers.

4) The “Third-Party Chaos” Interludes

Side characters and random social circumstances create pressure that neither con man can fully control. These moments make the cons feel risky and keep the humor grounded in

consequence, not just cleverness.

Opinions: What Aged Like Fine Wine (And What Didn’t)

What Holds Up

-

The craftsmanship: The pacing, the escalations, and the payoff structure feel deliberate. The movie knows when to speed up, when to pause, and when to let an

awkward silence do the work. - The chemistry: Caine and Martin don’t just “play off” each other; they create two competing comedic realities that collide scene after scene.

- The ending logic: The final act lands because the movie’s theme is deception, not romance or morality. It commits to its own rules.

What Feels Dated (But Still Discussable)

-

Some comedic targets: Like many comedies of its era, the film uses broad character exaggerations that can feel more uncomfortable to modern viewers,

depending on what you find funny versus what you find lazy. -

Gender dynamics: The premise revolves around men competing to manipulate women with money and charm. The film clearly satirizes this behavior, but it also

relies on it as entertainmentso viewer tolerance will vary. -

The “rich tourist” worldview: The movie’s moral math is basically: rich people can afford to be conned. That’s part of the joke, but it’s also a worldview

that can read differently now than it did in the late ’80s.

Legacy: Why It Keeps Showing Up in Pop Culture

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels isn’t just a standalone hitit’s part of a lineage. It’s a remake of Bedtime Story (1964), and its premise later got remixed again in

the gender-flipped film The Hustle (2019). It also inspired a Broadway musical adaptation that brought the con-man rivalry to the stage with a different kind of

showmanship: big production, big songs, and big punchlines.

The reason it adapts well is structural: a wager, a target, competing methods, escalating deception, and a payoff that can be tuned to different eras. The story is a machine, and

the machine runs on ego.

Practical Watch Guide: How to Enjoy It Like a Pro (Without Getting Scammed)

For first-time viewers

Don’t overthink it. Let the movie do what it does: set up social rules, then break them. If you try to “solve” the con early, you’ll still have funbut you’ll miss how carefully

the film trains your expectations.

For rewatchers

The rewatch value comes from watching performances rather than plot. Notice how often characters are “acting” even when they seem relaxed. Rewatching turns the film into a study

of delivery: pauses, facial control, and the strategic use of embarrassment.

For group movie nights

This is prime group viewing because it invites reactionsgasping at twists, laughing at physical comedy, and arguing about who “won” morally (spoiler: everyone is terrible,

and that’s the point).

So, Where Does It Rank Among Classic Comedies?

If you’re building a personal list of best ‘80s comedies, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels deserves a spot because it balances three things many comedies struggle to combine:

a clean structure, big comedic set pieces, and performances that don’t require you to be nostalgic to enjoy them.

In “con artist comedy” specifically, it’s elite-tier. It understands that the funniest lie is the one told with absolute confidenceand that the second funniest thing is watching

confidence collapse in real time.

Viewer Experiences: The 500-Word Add-On (Because This Movie Lives in People’s Heads Rent-Free)

The most common experience people have with Dirty Rotten Scoundrels is not just laughterit’s quote retention. You might not remember the exact order of

every scam, but you remember the feeling of a scene building toward a ridiculous payoff. That “I know something’s coming…oh no…OH YES” rhythm sticks. It’s the kind of comedy

that trains your brain to anticipate disaster the way a roller coaster trains your body to brace for the drop. Even viewers who haven’t seen it in years often remember specific

beats: the awkward politeness, the sudden escalation, and the way a simple interaction can become a full-blown performance.

Another shared experience is how the movie changes depending on who you watch it with. With friends who love physical comedy, the biggest laughs come from the

overcommitted performances and the sheer audacity of the situations. With viewers who prefer verbal humor, the fun is in the subtle one-upmanship: the way Lawrence maintains a

refined tone even when he’s clearly furious, or the way Freddy’s confidence makes his lies feel “almost plausible” for half a second. With a mixed crowd, the movie becomes a

social experimentpeople laugh at different moments, then spend the next five minutes trying to convince everyone else that their favorite scene is objectively the best scene

(which is, ironically, the exact energy of two con men arguing over territory).

There’s also a very modern experience that happens when newer viewers discover it: the “how is this still working?” surprise. The film is clearly from the late

’80s in pacing and style, yet it doesn’t rely on trendy references to be funny. Its humor is rooted in timeless mechanicsego, rivalry, manipulation, social status, and the human

tendency to believe what we want to believe. Watching it today can feel like seeing a well-built machine in a world full of disposable gadgets: it’s not flashy in the

modern way, but it’s sturdy, efficient, and oddly satisfying.

For many people, the movie becomes a “rewatch comfort pick,” not because it’s wholesome (it’s not), but because it’s predictably unpredictable. You know the film

will keep escalating. You know the characters will keep lying. And you know you’ll keep thinking, “Surely this is the peak,” right before it goes one notch further. That

reliability makes it a go-to choice for low-effort entertainment: you can half-watch it and still laugh, or fully watch it and admire how neatly the story threads tie together.

Finally, there’s the experience of post-movie debate. People love ranking it: best scam, best performance, best moment, best twist, best “I can’t believe they

tried that” scene. Those debates are part of the movie’s afterlife. And maybe that’s the most fitting legacy possible for a film about con artists: it keeps persuading audiences

to re-engage, re-argue, and rewatchgladly volunteering their time like it’s a charitable donation, except the charity is laughter and the collectors are Steve Martin and Michael

Caine.