Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What You’ll Learn

- Two Kinds of Trouble: Acute vs. Long-Term Diabetes Complications

- Hypoglycemia: When Blood Sugar Drops Too Low

- DKA and HHS: The High-Blood-Sugar Emergencies

- Long-Term Diabetes Complications (and Why They’re Not “Inevitable”)

- 1) Heart disease and stroke

- 2) Kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy)

- 3) Nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy)

- 4) Eye disease (diabetic retinopathy and more)

- 5) Foot complications: ulcers, infections, and Charcot foot

- 6) Oral health problems (yes, your mouth is part of your body)

- 7) Hearing and balance complications

- 8) Infections and slower healing

- When Something Feels “Off”: A Simple Action Plan

- How to Lower Your Risk: A Complications-Prevention Checklist

- Real-World Experiences: What Living With These Complications Can Look Like

- Conclusion

Diabetes is famous for one thingblood sugar. But the real plot twist is that blood sugar doesn’t stay in its lane.

When glucose runs too high for too long (or drops too low too fast), it can affect your brain, heart, kidneys, nerves,

eyes, feet, and even your teeth and ears. The good news: most diabetes complications are preventable or delayable.

The even better news: you don’t need to be perfectjust consistent.

This guide breaks down the big oneshypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA),

hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS), and common long-term complicationsplus practical ways to lower your risk.

(Educational content only, not a substitute for medical care.)

Two Kinds of Trouble: Acute vs. Long-Term Diabetes Complications

Think of diabetes complications like weather. Some are sudden storms. Others are slow climate shifts.

Both matter, but you prepare differently.

Acute complications (fast, sometimes scary)

Acute problems can show up within minutes to days. They’re often tied to medication timing, illness, dehydration,

missed insulin, or unexpected activity. The main “acute trio” is:

- Hypoglycemia (blood sugar too low)

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (dangerous acid buildup from ketones)

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) (severe dehydration + extremely high blood sugar)

Long-term complications (slow burn, big impact)

Chronic complications usually come from years of elevated glucose (plus blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, and genetics).

They tend to fall into two categories:

- Microvascular (small blood vessels): eye disease (retinopathy), kidney disease (nephropathy), nerve damage (neuropathy)

- Macrovascular (large blood vessels): heart disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease

Here’s the key point: you can’t change “having diabetes,” but you can absolutely change your odds of complications.

Hypoglycemia: When Blood Sugar Drops Too Low

Hypoglycemia typically means blood glucose below 70 mg/dL.

It’s most common in people who use insulin or certain diabetes medications that increase insulin release.

And yesyour body can be dramatic about it, because your brain runs on glucose like your phone runs on battery.

When the battery hits 1%, the alert gets loud.

Common hypoglycemia symptoms

Symptoms can vary, but many people notice a pattern. Some feel “shaky and sweaty.” Others feel “suddenly weird.”

Both are valid medical descriptions.

- Early signs: shakiness, sweating, hunger, fast heartbeat, anxiety, irritability

- Brain-related signs: headache, confusion, trouble concentrating, clumsiness, blurry vision, slurred speech

- Severe signs: seizures or loss of consciousness (medical emergency)

Why it happens (the usual suspects)

- Too much medication (more insulin than you needed, or a dose timing mix-up)

- Not enough food (skipped meal, delayed meal, or “I’ll just have coffee” turning into a 4-hour meeting)

- Unexpected activity (stairs count; your body doesn’t care that it wasn’t “a workout”)

- Alcohol (especially without foodyour liver gets distracted and stops releasing glucose as reliably)

- Illness (sometimes you eat less but keep the same meds)

What to do: the “15/15 rule” (and when it’s not enough)

A common approach for mild-to-moderate low blood sugar is:

15 grams of fast-acting carbs, wait 15 minutes, then recheck and repeat if still low.

Fast-acting carbs include glucose tablets, regular soda (not diet), juice, or plain sugar/honey.

Important: If someone is confused, unable to swallow safely, having a seizure, or unconscious,

treat it as an emergency. This is when glucagon may be needed and emergency care may be appropriate.

If you live with diabetes (or care for someone who does), it’s worth discussing glucagon options and a plan with a clinician.

Preventing hypoglycemia without living in fear

Preventing low blood sugar is less about “never mess up” and more about building guardrails:

- Know your patterns: Are lows more common after workouts? Overnight? Before dinner?

- Match meds to meals: If your schedule changes, your plan might need to change too.

- Use tools if available: Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and alerts can help catch lows earlier.

- Tell your team: Frequent lows may mean your regimen needs adjustment. That’s not failurethat’s calibration.

DKA and HHS: The High-Blood-Sugar Emergencies

If hypoglycemia is “too little sugar in the bloodstream,” DKA and HHS are “too much sugar,

plus the body struggling to cope.” Both are medical emergencies. Both often involve dehydration and electrolyte problems.

And both are easier to treat when caught early.

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA): what it is

DKA happens when the body doesn’t have enough insulin to use glucose for energy.

So it starts breaking down fat instead, producing ketones. Ketones are acidic, and when they build up,

they can make the blood dangerously acidic. DKA is more common in type 1 diabetes, but it can happen in type 2 diabetes too,

especially during severe illness or with certain medication scenarios.

Common DKA triggers

- Missed insulin or insulin pump problems

- Infection (flu, pneumonia, urinary tract infectionsyour body releases stress hormones that raise glucose)

- Major stress or trauma/surgery

- New diagnosis of diabetes (sometimes DKA is how type 1 is discovered)

DKA symptoms (when to take it seriously)

DKA can start with “classic high blood sugar” symptoms and escalate:

- Extreme thirst and frequent urination

- Nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain

- Deep/rapid breathing

- Fruity-smelling breath

- Confusion, severe fatigue, or trouble staying awake

If you suspect DKAespecially with vomiting, confusion, or rapid breathingseek urgent medical care.

Many diabetes plans include guidance for checking ketones during illness or sustained high readings.

How DKA is treated

DKA treatment is typically done in the emergency department or hospital and often includes:

IV fluids (rehydration), insulin, electrolyte replacement (like potassium),

and treatment of the underlying trigger (like an infection).

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS): the “desert dehydration” emergency

HHS is usually seen in type 2 diabetes and involves extremely high blood sugar levels,

severe dehydration, and high blood “osmolality” (your bloodstream becomes concentratedlike turning soup into paste).

Ketones and acidosis are typically minimal compared with DKA, but the dehydration and neurologic symptoms can be severe.

HHS symptoms

- Very high blood sugar (often dramatically elevated)

- Extreme thirst, dry mouth, and very frequent urination (then sometimes urination drops as dehydration worsens)

- Weakness, confusion, vision changes

- Seizures or decreased consciousness in severe cases

HHS is an emergencyespecially if confusion or severe dehydration is present. Prompt treatment with fluids,

insulin, and addressing the cause is critical.

Long-Term Diabetes Complications (and Why They’re Not “Inevitable”)

Long-term complications are not a guaranteed storyline. They’re a riskand risks can be reduced.

The big drivers are long-standing elevated glucose, high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels,

smoking, and limited access to consistent care. Let’s walk through the major categories.

1) Heart disease and stroke

Diabetes increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. High glucose can damage blood vessels,

and diabetes often travels with companions like high blood pressure and high cholesterollike an unwanted group project.

Over time, arteries can narrow (atherosclerosis), raising the risk of heart attack, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

The practical takeaway: complications prevention isn’t only about glucose. It’s also about the “big three”:

blood pressure, cholesterol, and smoking statusplus movement, sleep, and stress.

2) Kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy)

Your kidneys filter waste through tiny blood vessel clusters. Persistently high blood sugar can damage that delicate system,

leading to albumin in the urine (a sign of kidney stress) and a gradual decline in kidney function.

What helps most is early detection and risk management:

routine screening (often urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and estimated GFR), plus controlling glucose and blood pressure.

Many treatment plans also include kidney-protective medication strategies when appropriate.

3) Nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy)

Diabetic neuropathy often affects the legs and feet firstnumbness, tingling, burning, or pain.

But nerves that control internal organs can be affected too (called autonomic neuropathy), contributing to:

- Digestive problems (like nausea or delayed stomach emptying)

- Dizziness when standing (blood pressure regulation issues)

- Bladder symptoms

- Sexual dysfunction

The risk is not only discomfort. It’s also safety. If you can’t feel a blister, you can’t protect it

and that’s how small foot problems become big ones.

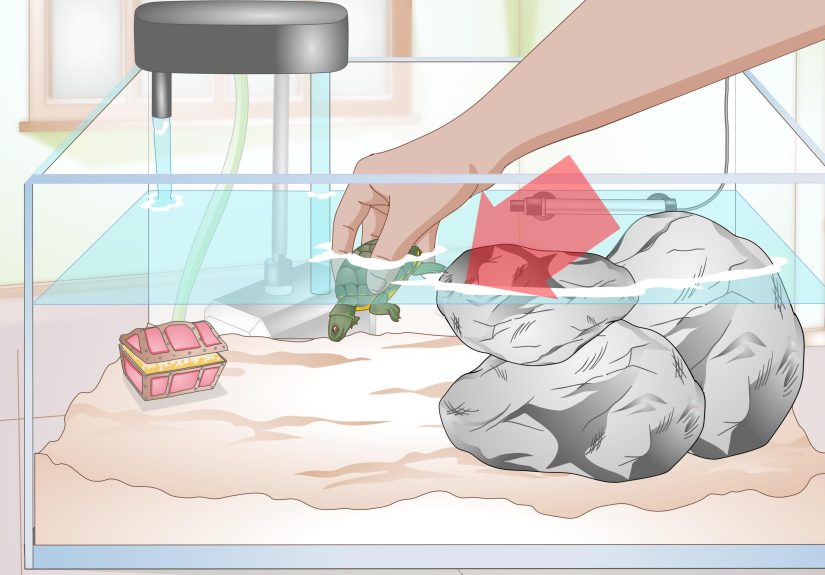

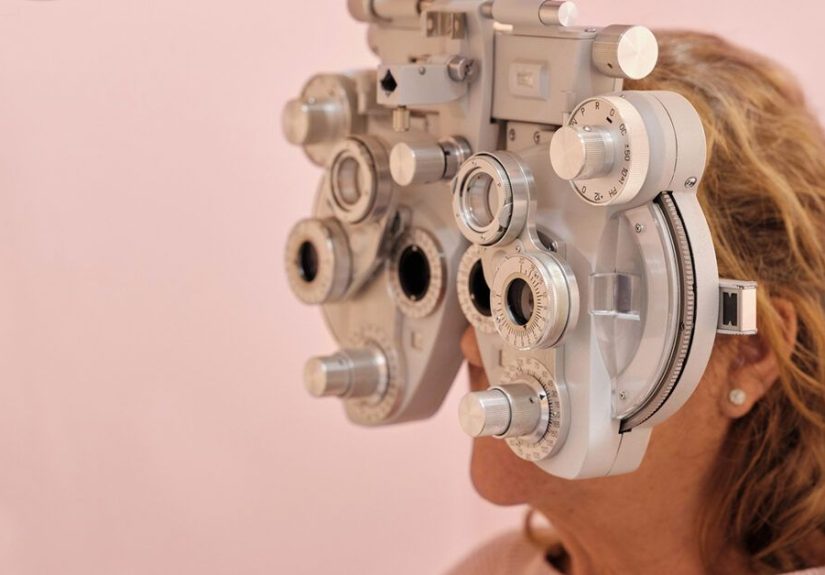

4) Eye disease (diabetic retinopathy and more)

Diabetic retinopathy involves damage to blood vessels in the retina.

Early on, it may cause no symptoms at allso waiting until vision changes can mean waiting too long.

That’s why regular dilated eye exams matter.

Diabetes also raises risk for other eye issues like cataracts and glaucoma.

If you notice new floaters, blurry vision, dark spots, or sudden changes, contact an eye professional promptly.

5) Foot complications: ulcers, infections, and Charcot foot

Diabetes can reduce blood flow and damage nerves in the feet. Put those together and you get a dangerous combo:

injuries that aren’t felt and wounds that heal slowly. Foot ulcers can start from something as boring as a shoe seam.

(The villain is never glamorous.)

Over time, severe nerve damage can also contribute to foot shape changes like Charcot foot,

where bones and joints weaken and shift. It’s uncommon, but it’s a reminder that “foot care” is not cosmetic

it’s preventative medicine.

6) Oral health problems (yes, your mouth is part of your body)

High blood sugar can increase sugar in saliva, feeding bacteria and raising the risk of cavities and gum disease.

Gum disease can also make diabetes harder to managean annoying two-way street.

Dry mouth, slow healing, and infections can show up too.

7) Hearing and balance complications

Diabetes-related nerve damage can affect many parts of the body, including the ears.

Some people experience hearing loss or balance issues over time. If you notice changes,

it’s worth bringing up during routine careespecially if it affects safety (like falls risk).

8) Infections and slower healing

High glucose can impair immune response and slow healing. Skin infections, urinary tract infections,

and fungal infections may be more common. Small cuts can take longer to healespecially in areas with reduced circulation.

This is why “don’t ignore that little sore” is actually excellent advice.

When Something Feels “Off”: A Simple Action Plan

You don’t need to diagnose yourself like a TV doctor. You just need a calm process.

- Check your glucose (if you can). If you use a CGM, confirm with a fingerstick if readings don’t match how you feel.

- Look for patterns: Did you eat? Take insulin? Exercise? Drink alcohol? Are you sick?

- Treat what you can safely treat: If low, use fast-acting carbs. If persistently high and you’re ill, follow your sick-day plan.

- Escalate early: If you have vomiting, confusion, severe dehydration, rapid breathing, or you can’t keep fluids down, seek urgent care.

Call emergency services immediately if someone with diabetes is unconscious, having a seizure,

cannot swallow safely, or is severely confused. Those are not “wait and see” moments.

How to Lower Your Risk: A Complications-Prevention Checklist

Prevention isn’t one magic trickit’s a playlist. You don’t need every song to be perfect; you need the overall vibe.

Daily and weekly habits

- Stay within your glucose goals as often as possible (and revisit goals as life changes).

- Take meds as prescribed and ask about dose adjustments if you’re having frequent lows or highs.

- Hydrate, especially during illness or heat.

- Move your body in ways you can repeat (walking counts; consistency beats intensity).

- Foot checks: look for redness, blisters, cuts, swelling, or hot spotsdaily if you have neuropathy.

- Don’t smoke. If you do, getting help to quit is one of the strongest complication-reduction moves available.

Routine screenings that actually matter

- A1C (how often depends on your plan and stability)

- Blood pressure checks

- Cholesterol/lipids monitoring

- Kidney screening: urine albumin + eGFR (often at least yearly, individualized)

- Dilated eye exams (often at least yearly, individualized)

- Foot exams (at least yearly in many care plans, more often if high risk)

- Dental cleanings and gum checks (ask your dentist what schedule fits your risk)

- Hearing/balance concerns: mention changes early, especially if falls risk is involved

Illness planning (the underrated superpower)

Many severe complications happen during illness because hormones drive glucose up while appetite and hydration go down.

Ask your clinician for a clear “sick-day plan,” including when to check ketones (if applicable),

when to adjust meds, and when to go in.

Mental health counts, too

Diabetes burnout is real. Stress can affect sleep, food choices, activity, and glucose.

If management feels overwhelming, support is a medical neednot a luxury.

Real-World Experiences: What Living With These Complications Can Look Like

The clinical definitions are important, but people live in the real worldwhere lunch meetings run long,

the flu shows up uninvited, and “just a quick errand” turns into a full cardio session.

The experiences below are composites of common situations many people with diabetes describe, designed to show how complications can unfold

and what tends to help. (Not personal medical advicejust real-life patterns.)

Experience 1: The “I’m fine… wait, why am I sweating?” low

A person takes their usual mealtime insulin, expecting to eat right away. Then a work call turns into a surprise fire drill.

Forty minutes later, they notice their hands trembling, their heart racing, and their thoughts getting oddly fuzzylike trying to read

through a foggy windshield. The tricky part is that hypoglycemia can feel like anxiety, impatience, or just being “hangry.”

They check their glucose and realize it’s below their target range.

What helps in this scenario is having a go-to plan that’s fast and boring: treat with quick carbs, recheck, then follow up with a more

sustaining snack once stable. The biggest lesson people mention is not the low itselfit’s that the low happened because the plan assumed

life would behave. Life did not behave.

Experience 2: The overnight low that feels like a weird dream

Some people describe nocturnal hypoglycemia as waking up drenched in sweat, disoriented, or having unusually vivid dreams.

Others don’t wake up at all and only discover it later through CGM dataor because they wake up exhausted and headachy.

Overnight lows can be linked to late-day exercise, alcohol, a basal insulin dose that’s a bit too strong, or a day when meals were lighter.

The “aha” moment many people share is that prevention often comes from patterns, not willpower: adjusting evening routines,

discussing basal doses, and using alerts when available. It’s also why family members or roommates sometimes learn what severe hypoglycemia looks like

and where emergency supplies are keptbecause if you’re asleep, “self-management” is limited.

Experience 3: DKA doesn’t always start with drama

DKA can begin quietly: a persistent high reading, thirst, frequent urination, and a feeling of being “off.”

During a stomach bug or flu, appetite drops and dehydration sneaks in. Some people try to power through,

thinking, “I’ll just rest and it’ll pass.” Then nausea worsens, breathing feels deeper or faster, and fatigue turns heavy.

By the time vomiting starts, keeping fluids down becomes hardmaking dehydration and ketone buildup worse.

The pattern people often report is that the earlier they escalatechecking ketones when recommended, contacting their care team,

and seeking urgent care when vomiting or rapid breathing appearsthe easier recovery tends to be. DKA is treatable,

but it’s not a “wait it out” situation.

Experience 4: The foot blister that “didn’t hurt,” until it did

A person with neuropathy buys new shoes and walks a little more than usual. Because the blister doesn’t hurt,

it’s easy to ignoreuntil a sock sticks to the skin or the area looks red and swollen.

People often describe feeling shocked that something so small can become a big deal.

That shock makes sense: when sensation is reduced and circulation is impaired, injuries don’t announce themselves loudly,

and healing may take longer.

The lesson many people learn (sometimes the hard way) is that foot care is less about fear and more about routine:

quick daily checks, well-fitting shoes, and early attention to any change. In diabetes management, “early” is a powerful word.

If there’s a single thread across these experiences, it’s this: complications aren’t moral judgments.

They’re signals. And with the right supportseducation, monitoring, medication adjustments, and timely carethose signals can be answered.