Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- From KiCad Board to Printable Box: The Big-Picture Workflow

- Getting a Clean 3D Model Out of KiCad

- Design Rules for 3D Printed Electronics Enclosures

- Planning Ports, Buttons, LEDs, and Ventilation

- Material Choices: PLA, PETG, ABS, and Friends

- Print Orientation and Practical 3D Printing Tips

- Real-World Lessons From 3D Printed KiCad Enclosures (Experience Section)

- Bringing It All Together

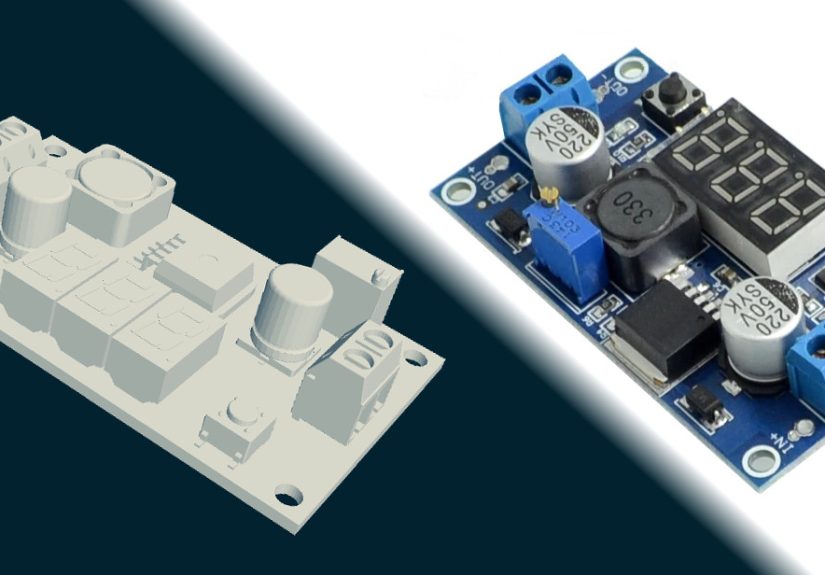

If you’ve ever held a bare PCB in your hand and thought, “You deserve a tiny plastic house,”

this guide is for you. Thanks to KiCad’s 3D viewer and modern desktop 3D printers,

it’s easier than ever to go from a blinking prototype on your bench to a fully enclosed gadget

that looks like it came off a factory line.

The original Hackaday piece on designing 3D printed enclosures for KiCad boards showed how

powerful that 3D view can be: once you can see your PCB in three dimensions, it’s only a short

hop to dropping it into a CAD program and wrapping it in plastic.

In this article, we’ll walk through a practical, modern workflowblending tips from KiCad users,

3D printing guides, and enclosure design prosto help you go from

“rough idea” to “click, print, assemble” with confidence.

From KiCad Board to Printable Box: The Big-Picture Workflow

Let’s start with the overall journey. Designing a 3D printed enclosure for a KiCad PCB usually

follows this flow:

- Finish your PCB layout in KiCad and make sure 3D models are assigned to major components.

- Export the board as a 3D model (usually STEP) from KiCad.

- Import the board into a mechanical CAD tool (FreeCAD, Fusion 360, SolidWorks, Onshape, etc.).

- Design your enclosure around the exact board geometry, including clearances and mounting features.

- Export the enclosure as STL and slice it for your 3D printer.

- Print, test-fit, tweak dimensions, and iterate until everything snaps together nicely.

The magic is that KiCad gives you a precise, realistic 3D model of your PCB. You’re not guessing

where that USB-C port isit’s exactly where the board says it is. Tools like

KiCad StepUp, a FreeCAD workbench, make this ECAD–MCAD bridge even smoother by

importing KiCad boards and footprints directly into FreeCAD.

Getting a Clean 3D Model Out of KiCad

1. Assign realistic 3D models to your components

Before you export anything, open KiCad’s PCB Editor and launch the 3D viewer. If you see anonymous

gray blobs or missing parts, you’re not ready yet. Make sure:

- Your footprints have 3D models assigned (either from the KiCad library or custom STEP/WRL files).

- Large mechanical partsconnectors, headers, switches, tall capacitorshave accurate models and heights.

- The board outline matches your final intended shape and size (no leftover sketch lines or rough drafts).

The better this 3D representation, the less “surprise sanding” you’ll be doing later.

2. Export PCB to STEP (and when VRML still matters)

In current KiCad versions, you can export your board via

File → Export → STEP to get a mechanical CAD–friendly model. This is the workhorse

option for most workflows and is supported by major CAD tools.

Some users still rely on VRML exports when they want the exact look of the 3D viewer, including tracks

and silkscreen graphics, then convert to other formats or bring everything in through StepUp.

For enclosure design, though, a clean STEP model (board + components) is usually enough.

3. Using KiCad StepUp and FreeCAD

KiCad StepUp sits at the center of many Hackaday-friendly workflows. It lets you:

- Pull a KiCad PCB directly into FreeCAD with components and holes in the right places.

- Push edited board outlines back to KiCad if you tweak the mechanical shape.

- Align mechanical parts (like a custom switch bracket) precisely with KiCad footprints.

Once your PCB is sitting in FreeCAD (or your CAD tool of choice), you can build the enclosure around it:

create a box, subtract the board volume for internal clearance, cut openings for ports, and add standoffs

and screw bosses.

Design Rules for 3D Printed Electronics Enclosures

Wall thickness and structural strength

Electronics enclosures don’t have to survive a war, but they do need to survive your backpack. Practical

guidelines from 3D printing services and enclosure design guides suggest:

- Wall thickness: 1.5–2.5 mm for most FDM-printed cases.

- Ribs and gussets: add internal ribs (1–1.5 mm thick) instead of just making the walls huge.

- Top surfaces: slightly thicker lids feel more rigid; 2.5–3 mm is common if you have space.

Thin walls save filament but flex like a phone case; thick walls feel solid but can warp and waste material.

Start in the 2 mm range and adjust based on your printer and filament.

Clearances and tolerances around your PCB

Tolerances are what separate “nice fit” from “why doesn’t this stupid board go in?” Different sources converge

on a few practical numbers:

- Gap between PCB edges and enclosure walls: 0.5–1.0 mm per side for FDM printing.

- Clearance around ports and cutouts: 0.2–0.3 mm for precise processes (SLA/SLS), closer to 0.5–1.0 mm for hobby FDM.

- Boss holes and slots: add ~0.25 mm of extra diameter for screw holes or pegs that must mate.

If your printer is dialed in, you can tighten these numbers; if you’re using a budget machine fresh out of the box,

be generous. Many designers create a simple “tolerance test” printrows of holes and slots at different offsetsto

see what fits their printer best before committing to a full enclosure.

Mounting the board: standoffs, screws, and snap fits

You’ve got a box, now you need the PCB to stay put inside it.

-

Standoffs and screws: The classic method. Use your PCB mounting holes in KiCad as reference and add

cylindrical standoffs in CAD. Leave a small tolerance between the screw and the printed hole, and consider using

heat-set threaded inserts if you’ll open the case often. -

Snap-fits: If you want a screwless design, 3D printed snap-fits work great when designed with

appropriate flexibility. Guides from professional printers suggest tuning fillet radii and cantilever length to avoid

brittle latches and using slightly larger tolerance (0.4–0.8 mm) at engagement surfaces. -

Side clamps: Small “fingers” or blocks that grip the edges of the board can hold it without extra holes,

useful if your PCB has no mounting holes but has reliable edge clearances.

Planning Ports, Buttons, LEDs, and Ventilation

Port cutouts and alignment

KiCad’s 3D model shines here. With the PCB loaded in CAD, you can:

- Create sketches on the inner face of the wall where a connector meets the enclosure.

- Project the connector’s outline, then offset it outward to add tolerance.

- Extrude that sketch as a cut to form the opening.

Add a little “comfort margin” around USB, HDMI, power jacks, and antenna connectors. Your hands will thank you when

the cable plugs in without scraping plastic.

Buttons and indicators

For buttons, you can:

- Use direct holes above tactile switches (with a small plunger printed into the lid), or

- Design a flexible “living hinge” button area that presses the switch underneath.

LEDs can shine through tiny holes, diffused light pipes, or thin “light windows” in translucent plastic. Many designers

simply leave 1–2 mm diameter holes above status LEDs; it’s simple and prints reliably.

Don’t forget airflow

Even small PCBs can get warm, especially with regulators, RF modules, or LEDs. Consider:

- Slots or grilles on the sides or top (angled vents can block dust and light while still breathing).

- Mounting holes for a small fan if you’re dealing with sustained high power.

- Leaving space around hot components so they’re not pressed tightly against plastic walls.

Material Choices: PLA, PETG, ABS, and Friends

Your enclosure is only as good as the plastic it’s printed in. Popular choices for desktop printers include:

-

PLA: Easy to print, nice surface finish, but can soften in hot cars or near warm power supplies.

Great for prototypes and indoor, low-heat devices. -

PETG: Tougher and more temperature-resistant than PLA; good for “real” gadgets that might see

sunlight or mild heat. -

ABS/ASA: More heat resistant and suitable for outdoor or automotive environments, but fussier to

print (warping, fumes, enclosure recommended). -

Nylons and engineering resins: Overkill for basic hobby projects, but ideal for rugged, impact-prone

devices or professional products.

Match the material to your use case: a garage sensor node might be happiest in PETG or ASA, while a desktop USB gadget

can live its best life in PLA.

Print Orientation and Practical 3D Printing Tips

Once the design is ready, you still have to think like a printer.

-

Orient for strength: Layer lines are weakest in the Z direction, so orient snap-fits and screw bosses

so they’re not relying on layer adhesion alone for strength. -

Minimize supports: Design overhangs with 45° chamfers instead of flat ceilings where possible.

Removing supports inside an enclosure is a special kind of frustration. - Use fillets: Rounded internal corners reduce stress concentration and help plastic flow during printing.

-

Test-print critical areas: Instead of printing the entire box over and over, slice a small “corner

sample” that includes a connector cutout, a standoff, and a piece of the lid.

Real-World Lessons From 3D Printed KiCad Enclosures (Experience Section)

Theory is great, but the real learning often happens at 2 a.m. when your fourth enclosure revision still doesn’t quite

fit. Here are some hard-earned lessons and experiences that tend to repeat across projects.

The USB port that wouldn’t plug in

A classic mistake: you carefully measure the USB connector footprint in KiCad, mirror the geometry in CAD, and create a

perfectly snug cutout. Then you print the enclosure, slide the board in, grab a cable… and discover that the plastic

wall is flush with the metal shell. There’s no room for the cable’s molded plug body.

The fix is simple but easy to forget: always design openings with the mated connector in mind, not just the

PCB-side socket. In practice, this means:

- Adding extra width and height around USB, HDMI, and barrel jack openings.

- Chamfering the entrance edges to guide the plug in.

- Leaving enough vertical clearance above the connector for stiff cables to bend comfortably.

FDM tolerances are real, and they vary

If you design enclosures based on “ideal” numbers from datasheets but ignore your printer’s personality, you’ll see

problems like:

- PCBs that only fit if you sand the edges.

- Lids that bow because internal standoffs are a hair too tall.

- Screw bosses that crack when you drive in a self-tapping screw.

The best strategy is to characterize your printer early. Print a small tolerance test block with stepped slots and

holes, then see what dimensions actually work. You can even keep a little notebook of “house tolerances”for example:

“For M3 holes, design at 2.8 mm; for sliding fits, add 0.3 mm clearance per side.” Doing this once can save several

failed enclosures later.

Version 1 is for learning, not shipping

When you export your first PCB from KiCad, drop it into CAD, and wrap a box around it, it’s tempting to treat that

first enclosure as “the one.” In reality, most projects benefit from at least two or three iterations:

- Rev A: Proves that the board fits at all and that mounting holes line up.

- Rev B: Refines the ergonomicscutouts, button feel, LED visibility, and assembly order.

- Rev C: Polishes the appearance: fillets, branding, nicer text labels, and any tweaks discovered in real use.

Don’t be afraid to print “ugly” prototypes with low infill or coarse layer heights just to validate fit. Once you’re

confident in the geometry, you can spend the extra time on a high-quality final print.

Designing for assembly (and re-assembly)

Most KiCad-based projects are tinkered with long after the “final” buildfirmware updates, solder rework, or new sensor

experiments. An enclosure that is a pain to open will make you resent your own design.

Experience suggests:

- Avoid permanently glued joints unless you’re absolutely done tinkering.

- Prefer four easily accessible screws over a complicated hidden latch system.

- Leave slack in internal wires and consider adding small cable channels or tie points.

It’s worth doing one test assembly where you intentionally take everything apart again. If you find yourself swearing,

redesign the case.

Using the enclosure as part of the design, not an afterthought

The happiest KiCad–3D printing experiences happen when you think about the enclosure while designing the PCB. A few

examples:

- Aligning connectors on one edge of the board to create a clean I/O “front panel.”

- Placing mounting holes in a rectangular pattern that’s easy to work with in CAD.

- Leaving space around tall components for internal ribs and screw bosses.

When the mechanical and electrical design are friends instead of strangers, your enclosure goes from “plastic box”

to “intentional product.”

Small touches that make it feel professional

Once you’re comfortable with the basics, you can add details that make your Hackaday-worthy build feel like a

commercial device:

- Embossed or debossed labels near connectors (“USB”, “POWER”, “RESET”).

- Subtle chamfers and fillets on external edges for a more polished look.

- Recessed areas for stickers, logos, or QR codes.

- Integrated feet or wall-mount ears for easier installation.

None of these add much design time once you’re used to your CAD workflow, but they dramatically change the perceived

quality of the final project.

Bringing It All Together

Designing 3D printed enclosures for KiCad PCBs is one of those skills that starts out feeling mysterious and quickly

becomes second nature. KiCad gives you a precise 3D view of your board; STEP exports and tools like StepUp bridge the

gap to mechanical CAD; and a bit of enclosure design know-how turns that bare PCB into a sturdy, good-looking device.

Start simple: export your next KiCad board, drop it in FreeCAD or your favorite CAD package, draw a basic box around

it, and print. From there, you can layer in better tolerances, smarter mounting, and more refined aesthetics. Before

long, every project on your bench will have a custom homeone that you designed, printed, and proudly show off.