Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Everyone Keeps Talking About “the Da Vinci Bridge”

- The Golden Horn Problem: A 1502 Mega-Span Request

- How a “No-Mortar” Stone Bridge Can Stand

- MIT’s 3D-Printed Proof: Turning a Sketch Into a Stress Test

- What This Says About Leonardo (and About Engineering)

- Where 3D Printing Fits in Modern Bridge Design

- FAQ: Quick Answers for Curious Bridge Nerds

- Hands-On Experiences: Da Vinci Bridge + MIT 3D Printing, Maker-Style (Extra )

- Conclusion

Leonardo da Vinci has a funny habit of showing up in places he absolutely shouldn’tlike your modern

engineering classroom. One minute he’s painting the Mona Lisa; the next he’s submitting a mega-bridge

proposal to an Ottoman sultan in 1502, basically saying, “Hi, yes, I can totally span your waterway with one

enormous arch. No, I won’t be attaching a full set of construction documents. Best wishes!”

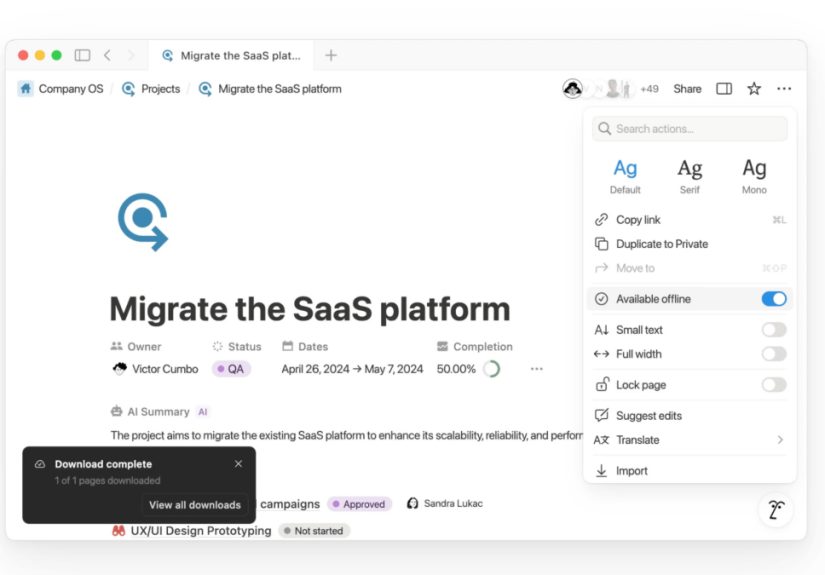

Fast-forward about five centuries, and a team at MIT decided to stop arguing about whether Leonardo’s bridge

would work and just… test it. Using 3D printing, they built a detailed scale model made of interlocking

“stones,” assembled it like a Renaissance-era puzzle, and proved the geometry was doing the heavy lifting.

The result is a perfect collision of old-world design and modern fabrication: the Da Vinci Bridge, verified

by MIT 3D printing.

Why Everyone Keeps Talking About “the Da Vinci Bridge”

When people say “Da Vinci Bridge,” they’re often mixing up two different ideas Leonardo is associated with:

a small, self-supporting wooden bridge concept (popular in classrooms and maker demos) and his much bigger,

historically documented proposal for a masonry bridge over Istanbul’s Golden Horn.

Bridge #1: The quick, self-supporting wooden bridge (the classroom favorite)

This is the one you’ll see made from dowels, sticks, or planks. Pieces interlock so that friction and

compression hold everything togetherno nails, no rope, no glue. It’s a great demonstration because it feels

like cheating: you build it in minutes, then stand back like you’ve just invented gravity.

Bridge #2: The Golden Horn masonry bridge (the MIT 3D-printed star)

This is the serious one: a single-span masonry bridge Leonardo proposed in 1502 to connect Istanbul and Galata

across the Golden Horn. It’s long, flattened, and ambitiousso ambitious that the obvious question becomes:

“Was this a brilliant engineered idea, or a beautiful sketch with big dreams?”

The Golden Horn Problem: A 1502 Mega-Span Request

In 1502, Sultan Bayezid II sought proposals for a bridge to connect Istanbul with Galata across the Golden Horn,

an important waterway where ships needed clearance. That detail matters: clearance pressures bridge geometry.

If you add lots of supporting piers in the water (a common strategy at the time), you risk blocking navigation.

If you try one big span, you risk… well, the entire bridge becoming a very expensive lesson in hubris.

Leonardo’s concept went bold: one enormous archflattened rather than semicirculartall enough for sailboats to

pass beneath, and long enough to be wildly out of step with typical bridge spans of that era. If it had been

built at full scale, it would have been a record-setter.

How a “No-Mortar” Stone Bridge Can Stand

The MIT experiment is easiest to appreciate if you understand one core idea: masonry arches are basically

compression machines. Stone is great at being squeezed and terrible at being pulled. A well-designed arch

arranges its blocks so gravity pushes them into each other, keeping the structure stable.

Compression: the stone-only superpower

Think of an arch as a force funnel. Loads on top get directed along curved pathways into the supports at the

ends. If the “line of thrust” (the path forces want to take) stays inside the thickness of the arch, the blocks

remain compressed, and the structure behaves. If it wanders outside, the arch tries to hinge, slide, or crack.

This is why the keystone matters. It’s not mystical. It’s just the final wedge that locks the geometry so the

blocks can’t easily shift into a failure mode. In an arch, the keystone is the moment the structure goes from

“supported by scaffolding” to “supported by physics.”

Flattened arch vs. semicircle: why the shape raised eyebrows

A semicircular arch is a classic: intuitive, sturdy, and common in historical masonry. But a flatter arch can

span farther while maintaining usable height and clearanceif you can manage the increased horizontal thrust at

the supports. That’s the trade: longer span, but bigger sideways push.

In Leonardo’s era, spanning a very long distance with masonry often meant multiple arches and many piers. A single,

long, flattened arch is a more daring move because it concentrates demands on the end supports and the foundation.

Splayed abutments: the “wide stance” stability trick

Leonardo’s design included abutments that splay outward rather than staying neatly aligned. Structurally, this

helps resist lateral motionwind, minor seismic activity, uneven ground behaviorby widening the base and

providing more geometric stability. Imagine someone balancing in a moving subway car: feet wider, wobble smaller.

Same vibe, fewer commuters.

MIT’s 3D-Printed Proof: Turning a Sketch Into a Stress Test

The MIT team approached the bridge like engineers with a historian’s respect: start with the surviving sketch

and historical constraints, assume plausible materials, reconstruct the geometry, and test whether the concept

can actually stand up using the structural logic Leonardo implied.

Step 1: Reverse-engineering the geometry

Leonardo didn’t leave a modern blueprint. So the team had to interpret the sketch, analyze what construction

methods and materials were realistic in the early 1500s, and translate the design into a buildable form. This

meant working out the bridge’s shape and how it could be divided into blocks (voussoirs) that could assemble into

a stable arch.

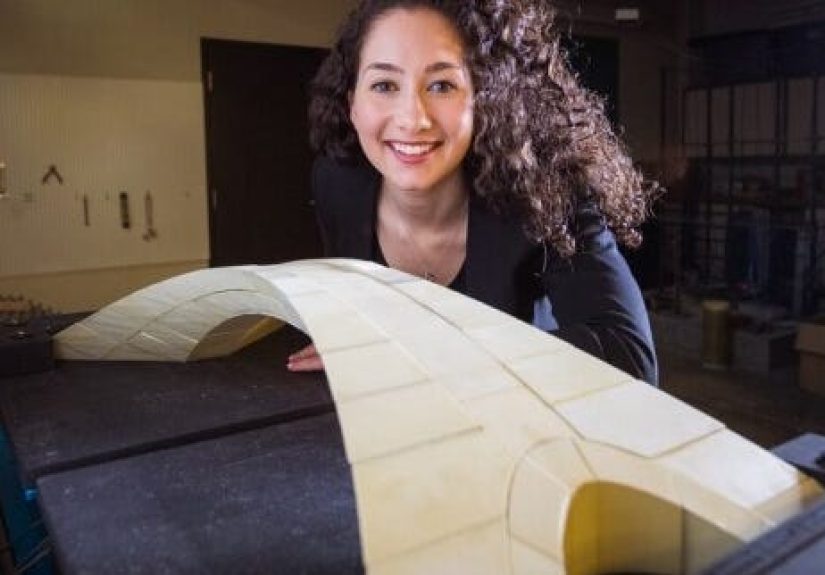

Step 2: Printing “stones” you can actually hold

At full scale, the bridge would require thousands of precisely cut stone blocks. For a lab test, the MIT team built

a 1:500 scale model using 126 3D-printed blocks. That’s the genius of 3D printing in this context: it can reproduce

complex geometry accurately, repeatedly, and fast enough to make iteration possible.

Each block was printed to match the shapes needed for the arch to behave like masonry: the key is not the material

being “stone,” but the way the pieces interact through contact and compression. The model ended up about 32 inches

longbig enough to handle and test, small enough to build without renting a crane.

Step 3: The keystone moment (a.k.a. “please don’t collapse right now”)

Like real masonry arch construction, the model was assembled on scaffolding. The blocks were placed until the last

piecethe keystonecould be inserted. Once the keystone went in, the structure could transfer forces through the arch

and into the supports. Then the scaffolding could be removed, and the bridge stood on its own.

This is the most charming part of the story because it’s deeply human: the bridge doesn’t slowly negotiate its

confidence. It either becomes a structure or becomes a pile of “we learned something today.” MIT’s model became a

structure.

Step 4: Testing settlement and sideways movement

A bridge that stands still in perfect conditions is nice. A bridge that stays stable when the ground misbehaves is

what you actually want in the real world.

To test resilience, the team built the model on two movable platforms and shifted one relative to the other to simulate

foundation settlement or ground movement. The bridge deformed slightly under horizontal movement, staying stable until

being pushed to collapse. In other words: it wasn’t indestructible, but it showed meaningful tolerance to the kind of

movement that can ruin rigid structuresespecially in earthquake-prone areas.

What This Says About Leonardo (and About Engineering)

Form is not decorationit’s the structure

One of the clearest lessons from the MIT test is that Leonardo’s form choice was doing real work. The bridge’s shape

isn’t just “pretty Renaissance curvature.” It’s the primary structural system. That is a very modern idea in spirit:

architecture and engineering aren’t separate teams yelling across a hallway; they’re the same conversation.

Designing for the site matters (even when your “site visit” is a sketchbook)

The Golden Horn’s conditionsspan length, ship clearance, soil behaviorare not optional details. They drive whether a

bridge design is sensible. MIT’s analysis emphasized the importance of geological context and how features like spread

footings and stabilizing geometry can make or break feasibility.

Prototyping beats arguing

The best part of the MIT story is that it’s a reminder to stop fighting hypotheticals with vibes. 3D printing made it

practical to build a testable physical model of a complex historic geometry and evaluate how it behaves under load and

movement. It’s the scientific method with a build plate.

Where 3D Printing Fits in Modern Bridge Design

MIT didn’t 3D print a real bridge for commuters; they 3D printed a question and then watched physics answer it.

That kind of prototyping is increasingly valuable in bridge engineering and architecture:

- Rapid physical validation of complex geometries before committing to expensive fabrication.

- Educational models that make structural behavior visible, not just theoretical.

- Iterationtweak a shape, print a new version, test again, and learn faster.

- Communicationa physical model helps teams and stakeholders “get it” immediately.

And outside the lab-scale world, 3D printing is also being explored for real structural components and even

experimental bridge prototypes. For example, one modern project in Italy built a small self-supporting bridge inspired

by Leonardo using 3D printing and stone waste materialsan example of how historic concepts can be reimagined with new

manufacturing approaches.

FAQ: Quick Answers for Curious Bridge Nerds

Did MIT 3D print a full-size Da Vinci Bridge?

No. MIT built a detailed 1:500 scale model using 3D-printed blocks to test feasibility, stability, and behavior under

movement. The value was in proving the geometry works, not in building a real crossing for traffic.

How many parts were in the MIT model?

The model used 126 interlocking blocks, designed to behave like a masonry arch where compression holds the structure

together.

Would the real bridge have been possible in 1502?

The evidence suggests the design was structurally feasible using stone masonry and period-appropriate construction

methodsthough the practical challenges (scale, precision stonecutting, foundations, logistics) would have been

enormous.

Is the Da Vinci Bridge “earthquake-proof”?

“Earthquake-proof” is a headline word, not an engineering guarantee. The MIT tests showed resilience to horizontal

movement and foundation settlement within limits. That suggests Leonardo’s stabilizing geometry was meaningful, but no

structure is immune to extreme conditions.

Hands-On Experiences: Da Vinci Bridge + MIT 3D Printing, Maker-Style (Extra )

If you’ve ever watched a bridge documentary and thought, “Cool, but I want a tiny dramatic version I can build on a

table,” you’re in luck. The Da Vinci Bridge story is surprisingly hands-onwhether you’re working with popsicle sticks

or a 3D printer. Here are a few real-world experiences people tend to have when they try the concepts for themselves,

plus what those moments teach you about structure, not just storytelling.

Experience 1: The “no-glue” wooden Da Vinci bridge feels like magic (until it doesn’t)

Building the self-supporting wooden version is often your first encounter with the idea that geometry can be a

fastener. You interlock sticks so each piece is both supported by and supporting the others. The first time you

remove your hands and it stays up, it’s hard not to grinpartly because it looks impossible, and partly because it

makes you feel like you just got promoted to “Renaissance wizard.”

Then comes the lesson: the bridge is stable because of contact, friction, and compression. If the sticks are too smooth,

too flexible, or mismatched in size, the structure slips. That “oops” moment is the point. It teaches that real bridges

aren’t just concepts; they’re tolerances, material behavior, and assembly realities.

Experience 2: A mini “MIT-style” 3D-printed arch turns you into a geometry perfectionist

If you have access to a school makerspace or a library 3D printer, try modeling a small arch made of individual

wedge-shaped blocks (voussoirs). The experience is very different from printing one solid arch. With separate blocks,

you immediately see why MIT used 3D printing: you need accurate shapes for the pieces to lock together under load.

The first assembly usually reveals something humbling: tiny print inaccuracies matter. If your pieces are slightly too

tight, the arch won’t seat properly. Slightly too loose, and it wobbles. When you finally get a “keystone” piece to

slide into place and the structure firms up, you feel the same structural logic that makes full-size masonry arches

work. It’s one of the clearest “aha” moments you can get without owning an entire quarry.

Experience 3: The “failure safari” teaches more than the success

Try deliberately changing one variable and watching what happens:

- Make the arch flatter (more span, more horizontal thrust) and see how the supports feel the difference.

- Remove or shrink the “splayed” side supports and notice how much easier it is to twist or slide the structure.

- Put the model on two books and gently shift one bookyour budget version of foundation settlement.

You’ll learn quickly that “stands up” is not the only goal. A good structure tolerates imperfect conditions. The MIT

work is compelling because it wasn’t satisfied with a photo-op; it explored movement and resilience.

Experience 4: Teaching the concept is weirdly satisfying

One of the best experiences with the Da Vinci Bridge topic is explaining it to someone elsebecause it forces you to

simplify without dumbing it down. Try this: place a few wedge-shaped pieces in an arc, support them with your hands,

then insert a final wedge. When the arch locks, you can literally point to the load path: “This is why it stays up.

Gravity pushes the blocks together.”

That’s the deeper reason this story stays popular. It’s not just that Leonardo was brilliant (he was), or that MIT has

cool 3D printers (they do). It’s that the bridge reveals a universal engineering truth: if you get the geometry right,

the structure almost wants to stand.

Conclusion

The Da Vinci Bridge is the rare historical “what if” that survives contact with reality. MIT’s 3D-printed experiment

shows that Leonardo’s Golden Horn proposal wasn’t just artistic ambitionit was structurally sound geometry, expressed

with minimal lines and maximum confidence.

The bigger takeaway isn’t “Leonardo was right” (though, yes). It’s that good design often looks simple because it’s

doing multiple jobs at once: spanning distance, providing clearance, resisting lateral motion, and working with the

site. And thanks to 3D printing, we can test those ideas quickly, learn from them, and maybejust maybefeel a tiny bit

like a Renaissance inventor without needing to write backward in a notebook.