Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What counts as a “blood clot” in lung cancer?

- Why lung cancer increases the risk of blood clots

- How serious is it? Understanding clot severity

- Warning signs: When to suspect a clot

- How doctors diagnose blood clots in lung cancer

- Treatment: How blood clots are managed with lung cancer

- Prevention: How to lower clot risk during lung cancer care

- Living with anticoagulants during lung cancer treatment

- Frequently asked questions (without the fluff)

- Key takeaways

- Experiences: what this can feel like in real life (and how people cope)

- Conclusion

Lung cancer already asks a lot of your body. Then blood clots can show up like an uninvited guest who not only eats your snacks, but also messes with your treatment schedule.

The good news: blood clots are often preventable, and they’re definitely treatableespecially when you know what to watch for.

In this guide, we’ll break down why lung cancer raises the risk of dangerous clots, what makes a clot “serious,” how doctors diagnose and treat them,

and what you can do (with your care team) to lower your riskwithout turning your life into a checklist app.

What counts as a “blood clot” in lung cancer?

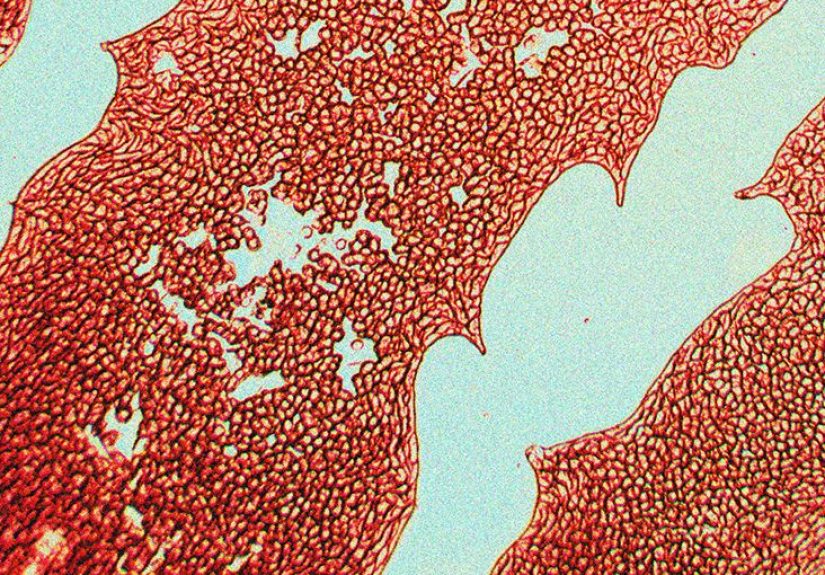

When clinicians talk about blood clots in people with lung cancer, they’re usually talking about venous thromboembolism (VTE).

That’s the umbrella term for clots that form in veins and can travel to the lungs.

Two big types you’ll hear about

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT): a clot most often in the deep veins of the leg or pelvis (sometimes the arm, especially if there’s a catheter).

- Pulmonary embolism (PE): a clot that travels to the lungs and blocks blood flow. This can be life-threatening and is treated as a medical emergency.

Clots can also occur in other locations, and (less commonly) cancer and certain treatments may be linked with arterial clots (in arteries),

which are associated with heart attacks or strokes. But for lung cancer, most “blood clot” conversations focus on DVT and PE.

Why lung cancer increases the risk of blood clots

Blood clots tend to form when the body’s normal balance of “clot” and “anti-clot” signals gets thrown off. In cancer, that balance can shift in a few ways at once.

Doctors often describe clot risk using a concept called Virchow’s triadthree forces that make clots more likely:

(1) blood that clots too easily, (2) slower blood flow, and (3) blood vessel injury.

Lung cancer and its treatments can push all three.

1) Cancer can make blood more “clot-happy”

Tumors can release substances that activate clotting. Cancer also increases inflammation, which can change how platelets and clotting proteins behave.

Translation: your blood can become more willing to form clotseven when it shouldn’t.

2) Treatments can add extra risk

Lung cancer treatment is lifesaving, but it can also stack the clot-risk deck:

- Hospitalization and reduced mobility: less movement means slower blood flow in the legs.

- Surgery: operations can injure vessels and temporarily increase clotting signals.

- Chemotherapy and some systemic therapies: certain drugs can raise clot risk, especially early in treatment.

- Central venous catheters (ports/PICCs): these can irritate veins and increase the risk of clots in the arm or chest veins.

3) Lung cancer–specific factors can matter

Some lung cancer situations are associated with higher clot risk, including advanced disease, recent diagnosis, active treatment, and situations that limit activity

(fatigue, pain, shortness of breath, or long periods in bed).

A key point: clots can happen even if you’re “doing everything right.” This is not a moral failing.

It’s biologyand biology is sometimes rude.

How serious is it? Understanding clot severity

“Severity” depends on where the clot is, how big it is, whether it’s blocking blood flow, and how your heart and lungs are handling the extra strain.

A clot in the wrong place can go from “mildly annoying” to “call 911” fast.

Why pulmonary embolism (PE) is treated as an emergency

A PE can reduce oxygen levels and increase pressure in the lung arteries. In severe cases, the heart has to work much harder to push blood through the lungs,

which can lead to shock or collapse. Some people have dramatic symptoms; others have subtle signs or no symptoms until complications develop.

Not all clots look dramatic (and that’s part of the problem)

Some PEs are found “incidentally” on a CT scan done for cancer staging or monitoring.

Even when discovered by accident, many still require treatment because they can grow or recur.

Your oncology team will weigh clot size/location, bleeding risk, symptoms, and overall treatment plan.

How blood clots can affect lung cancer care

- Treatment delays: a new clot may pause chemotherapy or procedures while anticoagulation is started.

- Hospital visits: diagnosis and stabilization often require urgent evaluation.

- Bleeding risk tradeoffs: treating clots means blood thinners, which can increase bleedingespecially around surgeries or invasive procedures.

- Long-term impact: some people develop chronic leg swelling after DVT or long-term breathing issues after PE (rare, but real).

Warning signs: When to suspect a clot

If you remember nothing else, remember this: new symptoms that are sudden, one-sided, or out of proportion deserve attention.

A clot is not the time to “wait and see if it’s just a weird Tuesday.”

Possible DVT symptoms (often in the leg)

- Swelling in one leg (or arm), especially if it’s new and not explained by injury

- Pain or tenderness, often in the calf or thigh

- Warmth, redness, or discoloration over the area

Possible PE symptoms (lungs)

- Sudden shortness of breath (at rest or with activity)

- Chest pain that may worsen with deep breaths or coughing

- Rapid breathing or a fast heart rate

- Coughing, sometimes with blood

- Feeling faint, lightheaded, or actually fainting

When to get emergency care

If you have sudden trouble breathing, chest pain, coughing up blood, severe dizziness/fainting, or blue/gray lips or skin,

treat it as an emergency and seek immediate care. If you’re in active cancer treatment, it’s better to be “overcautious” than “mysteriously tough.”

How doctors diagnose blood clots in lung cancer

Diagnosing clots is a mix of listening to symptoms, checking vital signs, and using imaging tests.

Because lung cancer can also cause shortness of breath and chest discomfort, clinicians often move quickly to rule out a PE.

Common tests for DVT

- Ultrasound: often the first-choice test for suspected leg (or arm) DVT.

Common tests for PE

- CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA): a CT scan with contrast dye to look for clots in lung arteries.

- V/Q scan: a ventilation-perfusion scan may be used when CT contrast isn’t ideal (for example, certain kidney issues or contrast allergy).

What about D-dimer?

D-dimer is a blood test that can be useful in some settings, but cancer can raise D-dimer levels even without a clot.

So in people with lung cancer, clinicians often rely more heavily on symptoms and imaging than on D-dimer alone.

Treatment: How blood clots are managed with lung cancer

The main goal is to prevent the clot from getting bigger, stop new clots from forming, and reduce the risk of the clot traveling (or causing more damage).

For most people, treatment centers on anticoagulationmedication that reduces the blood’s ability to clot.

Blood thinners (anticoagulants): the workhorse treatment

Several anticoagulants are used for cancer-associated clots. Your team’s choice depends on your clot location, kidney function, bleeding risk,

other medications (drug interactions matter), and whether you can take pills reliably.

-

DOACs (direct oral anticoagulants): medicines such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban are commonly used in many cancer patients.

They’re convenient because they’re oral and don’t require routine lab monitoring like warfarin. -

LMWH (low molecular weight heparin): an injectable anticoagulant that has long been a standard in cancer-associated thrombosis.

It’s still preferred in some scenarios (for example, higher bleeding risk situations or certain medication interactions). -

Warfarin: used less often now for cancer-associated VTE because it requires frequent INR checks and is affected by diet and many medications.

But it may still be appropriate in select cases.

How long is treatment?

Many people with active cancer need anticoagulation for at least 3 to 6 months, and sometimes longer while cancer is active or treatment continues.

Your team will reassess regularly, balancing clot recurrence risk against bleeding risk.

When treatment needs to be more aggressive

If a PE is large and causing severe symptoms or low blood pressure, doctors may consider:

- Thrombolysis (“clot-busting” medication): used selectively because it carries higher bleeding risk.

- Thrombectomy: physically removing the clot via a catheter-based procedure in certain severe cases.

- IVC filter: a device placed in the large vein (vena cava) to catch clots traveling from the legs to the lungs.

This is usually reserved for people who can’t take anticoagulants or have recurrent clots despite treatment.

Bleeding risk: the tradeoff you and your team must manage

Anticoagulants don’t “melt” clots like soap dissolves grease. They prevent growth and new clot formation while your body slowly breaks the clot down.

That’s why bleeding risk matters: you’re intentionally turning down the clotting system’s volume.

Call your care team promptly if you notice unusual bleeding (frequent nosebleeds, blood in urine or stool, vomiting blood, severe headaches, or sudden weakness),

or if bruises appear without explanation and keep multiplying like rabbits.

Prevention: How to lower clot risk during lung cancer care

Not everyone with lung cancer should automatically take a blood thinner “just in case.”

Preventive anticoagulation depends on your risk level and bleeding risk, and it’s a decision best made with your oncology team.

That said, there are practical steps that help many people.

1) Keep your care team in the loop about clot risk

Ask: “Am I at high risk for clots right now?” This is especially important if you’re:

starting a new systemic therapy, being hospitalized, having surgery, getting a port/PICC, or noticing reduced activity.

2) Move when you can (even small amounts count)

If you’re able, short walks and ankle circles can encourage blood flow.

Example: after a long infusion visit or car ride, a few minutes of gentle movement can help (as long as your clinician says it’s safe).

3) Hydration and “compression” strategiesonly when appropriate

Staying hydrated can support circulation. Compression stockings may be recommended for some people, but they aren’t right for everyone.

If you have leg artery disease, significant swelling of unknown cause, or severe pain, get clinician advice first.

4) Follow post-surgery prevention plans closely

After lung cancer surgery, clinicians may prescribe short-term blood thinners and encourage early ambulation.

If you’re sent home with injections or pills, take them exactly as directedthis is one of those “annoying but powerful” steps.

5) Don’t ignore catheter/port symptoms

If you have a PICC or port and develop arm swelling, pain, redness, or prominent veins in the chest/arm,

notify your team quickly. Catheter-related clots are a known issue, and prompt evaluation matters.

Living with anticoagulants during lung cancer treatment

Taking a blood thinner while juggling oncology appointments can feel like adding a side quest to a game you didn’t choose.

The most helpful approach is to make anticoagulation boringboring is good. Boring means consistent.

Practical tips that often help

- Use one pharmacy when possible: it improves interaction screening.

- Keep a medication list updated: include supplementssome increase bleeding risk.

- Tell every clinician you’re on a blood thinner: especially before procedures or dental work.

- Take doses on schedule: set alarms; don’t “double up” unless a clinician tells you to.

If you’re worried about cost, dosing, injections, or side effects, say so out loud. There may be alternative drugs,

financial assistance programs, or a different plan that’s safer for you.

Frequently asked questions (without the fluff)

Can a blood clot be the first sign of lung cancer?

Sometimes a new clot prompts medical workups that reveal an underlying cancer, especially in people with unprovoked VTE.

But most clots have multiple contributing factors, and a clot alone doesn’t mean someone has cancer.

Are blood clots more common early in lung cancer treatment?

Risk is often higher around diagnosis and the first months of treatment, when the body is under stress and therapies are starting.

That’s why early symptom awareness and prevention planning can be especially valuable.

Do blood thinners interfere with chemotherapy or immunotherapy?

Many people receive anticoagulants and cancer therapy at the same time. The key issues are bleeding risk, kidney/liver function,

drug-drug interactions, and timing around procedures. Your oncology and hematology teams coordinate these decisions.

Key takeaways

- Lung cancer and its treatments can significantly increase the risk of DVT and PE.

- PE can be life-threatening; sudden shortness of breath or chest pain needs urgent evaluation.

- Most clots are treatable with anticoagulants, and many people can continue cancer treatment with careful planning.

- Prevention is individualizedmovement, post-surgery plans, and catheter awareness matter.

- When in doubt, call your care team. “I don’t want to bother anyone” is not a medical strategy.

Experiences: what this can feel like in real life (and how people cope)

Medical facts are important, but real life is where clots actually happenusually when someone is already tired, already overwhelmed,

and already sick of hearing the word “important.” Below are experiences commonly described by people with lung cancer and caregivers,

plus practical coping ideas that clinicians often reinforce. (No two journeys are identical, but patterns show up.)

The “my leg looks like it joined a different body” moment

One of the most common DVT stories starts with a subtle annoyance: a calf that feels tight, a sock mark that seems deeper than usual,

or a leg that aches like it ran a marathon… despite the person not running anywhere except to the bathroom.

Then someone notices the key detail: it’s mostly one-sided. That’s often what pushes people to call.

Many describe feeling surprised that something potentially serious can masquerade as “a cramp” or “sleeping wrong.”

Coping tip: if you’re in treatment, consider doing a quick daily “mismatch check” when you get dresseddoes one leg look more swollen?

Is one arm puffier around the catheter side? Not obsessively, just enough to spot a meaningful change.

The “Is this anxiety… or is this my lungs?” debate

PE symptoms can be confusing because lung cancer itself can cause shortness of breath.

People often describe a “different” breathlessnessmore sudden, more intense, or paired with sharp chest pain that flares with deep breaths.

Some say it felt like they couldn’t catch a full breath even while sitting still.

Others noticed their heart racing for no obvious reason, like their body hit the panic button without consulting their brain first.

Coping tip: don’t try to self-diagnose the difference between “cancer shortness of breath” and “clot shortness of breath.”

If it’s sudden, new, worsening, or paired with chest pain, get checked. It’s not dramatic; it’s responsible.

Starting blood thinners: relief, then… logistics

Many people feel immediate relief once there’s a planbecause uncertainty is exhausting.

Then comes the practical reality: pills on a schedule, bruises that appear like you fought a coffee table and lost,

and questions like “Can I still take this supplement?” or “What if I miss a dose?”

If injections are used, people often say the fear is worse than the actual needleuntil about day three, when they become a reluctant expert.

Coping tip: aim for consistency over perfection. Use alarms. Keep a simple medication card in your wallet.

Tell your care team about bleeding symptoms earlysmall issues are easier to fix than big ones.

Caregiver experience: the emotional whiplash

Caregivers often describe clots as emotionally jarring because they can appear suddenly, require urgent evaluation,

and shift the focus from cancer treatment to “stabilize this now.” It can feel like getting yanked into a surprise storm.

Many caregivers also struggle with when to push for care versus “not overreacting.”

Coping tip: agree ahead of time on a simple rule: new sudden breathing trouble or chest pain = urgent evaluation.

Having a shared rule reduces debate in stressful moments.

Getting back to “normal-ish”

After the immediate scare passes, people often worry about recurrenceespecially during long infusions, car rides, or periods of fatigue.

The goal isn’t to live in fear; it’s to build a routine that reduces risk without taking over your life.

Many find comfort in small, repeatable habits: standing up every hour when possible, doing ankle pumps during long sits,

asking about clot prevention around surgery, and checking in about whether anticoagulation duration still makes sense.

And yespeople also learn to laugh again. Sometimes the humor is dark, sometimes it’s silly, and sometimes it’s just the joy of

texting a friend: “Good news: it’s not pneumonia. Bad news: my blood tried to invent cement.” If laughter shows up, let it.

It doesn’t minimize the seriousnessit makes the load carryable.