Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Body Shape” Actually Means (Hint: It’s Not About Being Hot)

- The Common Body Shapes (And Why They’re Oversimplified)

- Visceral Fat vs Subcutaneous Fat: The Health Plot Twist

- How Different Fat Patterns Can Affect Health

- How to Measure Health-Relevant Body Shape (Without Obsessing)

- Why Your Body Stores Fat Where It Does

- Health Improvements That Matter More Than Chasing a New Shape

- Myths That Make People Miserable (And Usually Don’t Work)

- Everyday Experiences People Have When They Stop Chasing Shape and Start Building Health (Extra 500+ Words)

- 1) “My Waist Didn’t Change Much, But My Numbers Did”

- 2) “Strength Training Changed How I Feel in My Body”

- 3) “I Stopped Using One Measurement as My Whole Personality”

- 4) “My Body Shape Shifted During Life Changesand That Wasn’t Failure”

- 5) “I Learned the Difference Between ‘Weight Loss’ and ‘Health Gain’”

- 6) “My Relationship With Food Got Healthier When I Focused on Fuel”

- Conclusion: Let Body Shape Be a Clue, Not a Verdict

If you’ve ever been told you’re an “apple,” a “pear,” or (my personal favorite) a “rectangle,” you’ve already met the

world’s weirdest fruit salad: body shape categories. They’re often used for clothing advice, but

there’s a real health conversation hiding underneath the fashion talk. Not because any shape is “better,” but because

where your body stores fat (and how much muscle you carry) can influence your risk for certain

conditionsespecially heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Important tone-setter: your body is not a math problem you have to solve to “deserve” health. And body shape is not a

moral report card. It’s simply one cluelike blood pressure, sleep quality, or family historythat can help you make

smarter choices for your long-term wellness.

What “Body Shape” Actually Means (Hint: It’s Not About Being Hot)

When people say “body shape,” they’re usually describing fat distributionhow weight tends to show

up on your body. Some people store more around the midsection, others around the hips and thighs, and many people land

somewhere in between. Genetics play a huge role, but hormones, age, stress, sleep, medications, and activity levels

can all nudge the pattern over time.

From a health perspective, the big question is less “What shape am I?” and more:

How much fat is stored deep in my belly versus under my skin? That difference matters.

The Common Body Shapes (And Why They’re Oversimplified)

These labels are shorthand, not science. Real bodies don’t come in five neat boxes. Still, the categories can help you

understand typical fat-storage patterns:

Apple (More Weight Around the Midsection)

An apple shape often means more weight is carried around the abdomen. This can correlate with higher

amounts of visceral fat (the kind that wraps around internal organs), which is more strongly linked

to cardiometabolic risk.

Pear (More Weight Around Hips and Thighs)

A pear shape usually means more fat stored around the hips, butt, and thighsoften more

subcutaneous fat (stored under the skin). In many studies, gluteofemoral fat is associated with a

lower risk profile than visceral fat, although total health risk still depends on many factors.

Hourglass (More Even Distribution With a Defined Waist)

An hourglass shape suggests weight is distributed more evenly between upper and lower body with a

narrower waist. Health risk still depends on visceral fat levels, overall body composition, and lifestylenot the

silhouette.

Rectangle (Less Waist Definition, More Even Up/Down)

A rectangle shape can mean weight is distributed fairly evenly with less waist-to-hip contrast.

People in this category can be very lean, very muscular, or somewhere in the middle. The key health question remains

visceral fat and muscle mass.

Inverted Triangle (More Weight in the Upper Body)

An inverted triangle shape often means broader shoulders or more weight carried in the chest/upper

back area. Depending on where fat is stored (subcutaneous vs visceral), risk can vary widely.

Bottom line: body shape labels are a map drawn with a chunky marker. Helpful for direction, not for street-level

detail.

Visceral Fat vs Subcutaneous Fat: The Health Plot Twist

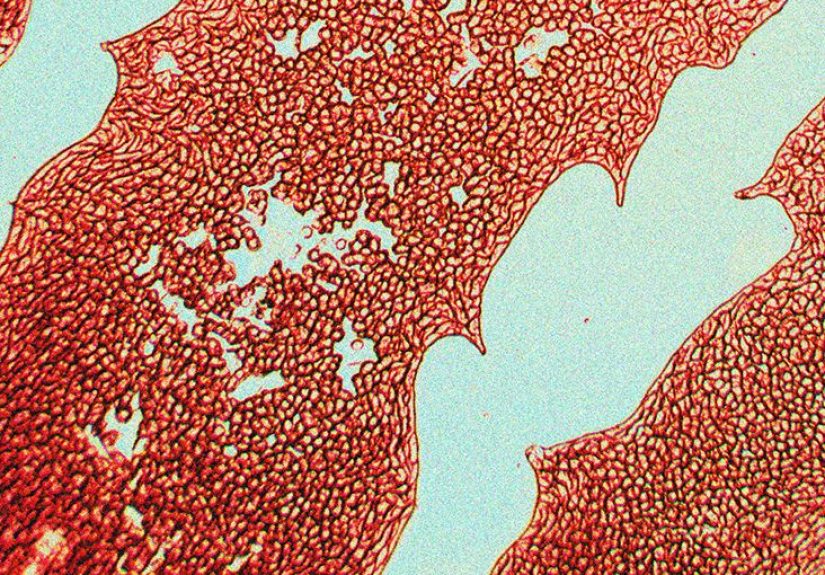

The reason “apple vs pear” shows up in health discussions is because fat isn’t one uniform thing.

-

Subcutaneous fat sits under the skin (think: pinchable). It can still affect health when present in

high amounts, but it’s generally less metabolically active. -

Visceral fat sits deeper in the abdomen, surrounding organs. It’s more strongly associated with

inflammation, insulin resistance, higher triglycerides, and increased cardiometabolic risk.

Visceral fat is part of why two people with the same scale weight or BMI can have very different health profiles.

That’s also why “I’m not overweight, so I’m automatically fine” can be a trapand why “I’m overweight, so I’m doomed”

is equally wrong.

How Different Fat Patterns Can Affect Health

Let’s connect body-shape patterns to what they can (and cannot) suggest about health. This isn’t destinyit’s risk

awareness.

Central Weight Gain (Apple Pattern): Higher Cardiometabolic Risk Signals

Carrying more weight around the waist is associated with higher risk for:

type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol patterns, fatty liver disease, and heart disease.

This is largely because central fat storage is more likely to include visceral fat.

Example: Two adults both have a BMI of 27. One stores most fat around hips and thighs, while the other has a larger

waist and higher waist-to-height ratio. The second person is more likely to have insulin resistance or elevated

triglycerideseven if their weight is the same.

Lower-Body Weight Gain (Pear Pattern): Often Lower Risk, But Not “Risk-Free”

A pear-shaped pattern is often associated with a comparatively lower cardiometabolic risk than central weight gain.

But health still depends on the full picture: activity level, diet quality, sleep, stress, genetics, and whether

overall body fat is high enough to strain blood sugar, joints, or blood pressure.

Also, “pear” doesn’t mean you can ignore your waist measurement forever. Bodies change with age, hormones, and life

events (hello, stress and menopause). Many people become more centrally distributed over time.

“Normal Weight” but Higher Body Fat: The Sneaky Middle

Some people look lean but carry relatively higher body fat and lower muscle masssometimes called “normal weight

obesity” in research settings. This can happen with sedentary habits, aging, crash dieting cycles, or not enough

strength training. The scale might look “fine,” but metabolic markers may not.

If that sounds alarming, breathe. The fix is usually not extreme dietingit’s improving body composition with

consistent movement, strength training, protein and fiber, and better sleep.

Low Muscle + Higher Fat (Sarcopenic Obesity): Why Strength Matters

Muscle is metabolically helpful: it supports glucose regulation, mobility, and resilience as you age. When muscle mass

drops and fat increases, risk can rise even if weight doesn’t change dramatically. This is one reason doctors and

dietitians increasingly talk about body composition, not just weight.

How to Measure Health-Relevant Body Shape (Without Obsessing)

If you want a practical, health-focused way to think about body shape, these measures are more meaningful than

“apple/pear” labels.

Waist Circumference

Waist circumference is a simple screening tool for abdominal fat. Many clinical guidelines use cutoffs (often around

35 inches for women and 40 inches for men) to flag higher cardiometabolic risk in

adults, though ideal thresholds can vary by individual factors and ethnicity.

Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR)

WHR compares waist size to hip size. A higher ratio can suggest more central fat storage. It’s useful, but it can also

be influenced by hip structure and muscle mass.

Waist-to-Height Ratio

Many clinicians like this because it adjusts for height. A common rule of thumb is keeping waist circumference less

than about half your height, but it’s still a screening toolnot a diagnosis.

BMI (Helpful, Limited)

BMI can be useful for large population trends, but it doesn’t distinguish muscle from fat, and it says nothing about

where fat is stored. Athletes may have a high BMI with low body fat; others may have a “normal” BMI with higher

visceral fat.

Body Fat and Body Composition Testing

Methods like DEXA scans, bioelectrical impedance scales, or caliper measurements can estimate body fat percentage.

They’re not perfect, but they can offer more insight than weight aloneespecially when tracked over time.

If you’re a teen or still growing: measurements and “cutoffs” can be confusing and sometimes harmful.

The healthiest move is focusing on strong habits and checking in with a pediatric clinician if you have concerns,

rather than trying to “optimize” your shape.

Why Your Body Stores Fat Where It Does

Your body shape is influenced by a surprisingly long guest list:

- Genetics: Family patterns matter a lot.

- Hormones: Estrogen and testosterone affect fat distribution; pregnancy and menopause can shift patterns.

- Stress and sleep: Chronic stress and poor sleep can influence appetite, cravings, and fat storage signals.

- Activity level: Strength training supports muscle; sedentary time can tilt body composition in the wrong direction.

- Diet quality: Ultra-processed, high-sugar patterns can worsen insulin resistance in susceptible people.

- Medical factors: Some medications and conditions can affect weight distribution and metabolism.

Translation: if you’ve ever blamed yourself for not being able to “change your shape,” your body would like to file a

formal complaint. You can improve health risk markersoften dramaticallywithout becoming a different geometry.

Health Improvements That Matter More Than Chasing a New Shape

If your goal is better health, focus on what reliably moves the needle: blood sugar control, cardiovascular fitness,

strength, sleep, and stress management. Here’s what that can look like in real life.

Build Muscle (It’s the Most Underrated “Health Insurance”)

Strength training improves insulin sensitivity, supports joints, and helps preserve muscle with age. You don’t need a

complicated routine. Two to four sessions per week using bodyweight, resistance bands, or weights can help.

Not into gyms? Great. Squats, push-ups (wall counts), lunges, rows with a band, and carrying heavy groceries like a

champion all qualify.

Move More in a Way You’ll Actually Repeat

Cardiovascular exercise supports heart health and can reduce visceral fat over time. Walking, cycling, swimming,

dancing, sportspick something you can tolerate on a bad day, because consistency beats intensity.

Bonus: the most powerful “workout” is often the one you forget is a workout (walking a friend, playing a sport, taking

the stairs, cleaning like you’re mad at the dust).

Eat for Metabolic Health, Not for Punishment

Health-forward eating patterns tend to share a few traits:

more fiber (vegetables, beans, fruit, whole grains),

enough protein (fish, poultry, eggs, tofu, yogurt, legumes),

healthy fats (nuts, olive oil, avocado),

and fewer added sugars and heavily processed foods.

You don’t need a “perfect” diet. Try upgrades you can keep:

add a fruit or veggie at breakfast, swap sugary drinks for water some days, and include protein at meals so you’re not

starving at 4 p.m. and negotiating with a vending machine.

Sleep and Stress: Not Optional Extras

Poor sleep can make hunger hormones and cravings louder and reduce motivation for movement. Chronic stress can push

people toward quick comfort foods and disrupt recovery. Aim for a sleep routine you can repeat, and treat stress

management like a skill: walking outside, journaling, breathing exercises, talking with someone you trust, or asking

a professional for support.

Check Your Numbers (Because Your Waist Isn’t Your Only Metric)

If you’re concerned about health riskespecially with a strong family historyconsider discussing screening with a

clinician: blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, blood glucose or A1C, and liver enzymes can offer a clearer

picture than body shape alone.

Myths That Make People Miserable (And Usually Don’t Work)

Myth: You Can “Spot Reduce” Belly Fat With 500 Crunches

Ab exercises strengthen muscles, but they don’t specifically melt fat from that area. Fat loss happens system-wide,

influenced by energy balance, hormones, genetics, and lifestyle. Keep the crunches if you like themjust don’t expect

them to negotiate directly with your waistline.

Myth: Your Shape = Your Fate

Body shape can hint at risk, but it doesn’t write your future. People with central weight gain can improve blood sugar

and lipid profiles significantly with strength training, better sleep, and nutrition upgradessometimes with minimal

scale change.

Myth: The Scale Is the Only Scoreboard

Your health wins can look like: walking farther without getting winded, lifting heavier, better lab values, improved

mood, fewer cravings, more energy, and steadier sleep. None of those require you to become a different “shape.”

Everyday Experiences People Have When They Stop Chasing Shape and Start Building Health (Extra 500+ Words)

The internet loves dramatic “before-and-after” photos. Real life is usually more like “before-and-after I finally

found pants that don’t annoy me.” Here are common experiences people share when they focus on health behaviors instead

of trying to force their body into a specific category:

1) “My Waist Didn’t Change Much, But My Numbers Did”

Many people notice their lab results improve before their body looks different. Someone might keep the same jeans size

but see their A1C drop, blood pressure improve, or triglycerides come down after a few months of consistent walking

and basic strength training. It’s a reminder that internal health can move faster than the mirror.

2) “Strength Training Changed How I Feel in My Body”

People often describe a shift from “I need to shrink” to “I want to be strong enough for my life.” Carrying groceries,

sitting and standing without knee complaints, climbing stairs without feeling like a Victorian fainting scenethese are

practical wins. Even if someone remains apple-shaped or pear-shaped, more muscle can improve posture, balance, and

everyday confidence.

3) “I Stopped Using One Measurement as My Whole Personality”

It’s surprisingly freeing when someone stops treating waist circumference like a daily grade. A common experience is

switching to periodic check-ins (monthly or quarterly) or focusing on non-body goals: consistent sleep, a weekly step

target, cooking at home a few nights, or learning to lift safely. Anxiety often goes down when the process becomes

about habits rather than constant body surveillance.

4) “My Body Shape Shifted During Life Changesand That Wasn’t Failure”

People going through puberty, pregnancy/postpartum life, menopause, college stress, a new job, or a rough year often

notice changes in where they store fat. Many describe guilt at first, then relief once they understand that hormones

and stress physiology can shift distribution. The healthier turning point is usually: accepting the change, rebuilding

routines, and getting support (medical, mental health, social) instead of launching into extreme restriction.

5) “I Learned the Difference Between ‘Weight Loss’ and ‘Health Gain’”

Some people lose weight and feel worsetired, cranky, weaker, and obsessed with foodbecause they cut too hard or

skipped strength training. Others gain weight but improve health markers by building muscle, sleeping better, and

eating more consistently. Many report that the most sustainable approach is slower and less dramatic: protein at meals,

more fiber, fewer liquid calories, and movement they don’t dread. The most repeated line is basically: “I wish I’d

started with the boring basics sooner.”

6) “My Relationship With Food Got Healthier When I Focused on Fuel”

A lot of people with body-shape anxiety cycle between strict rules and “I blew it, so whatever.” When they shift to

fueling performance and energyespecially pairing carbs with protein and adding fiberhunger becomes more predictable,

cravings calm down, and meals feel less like a negotiation. For teens in particular, this approach matters: growing

bodies need enough energy, and extreme dieting can backfire physically and mentally.

The shared theme across these experiences is that health is a practice, not a body type. When people

treat their body like a teammate instead of a project, they tend to stick with habits long enough to get real results.

Conclusion: Let Body Shape Be a Clue, Not a Verdict

Body shapes can offer a useful starting point because they hint at fat distributionand fat distribution can influence

metabolic health risk. But your “shape” is only one piece of the puzzle. The more powerful story is what you do with

the information: building strength, moving consistently, eating in a way that supports stable energy and blood sugar,

sleeping better, managing stress, and checking health markers when needed.

Whether you’re an apple, a pear, a rectangle, an hourglass, or a “human being with a body that changes,” the best goal

isn’t to chase a silhouette. It’s to build a lifestyle that keeps your heart, muscles, and metabolism working with you

for the long haul.