Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Ads Can “Ruin” Pop Culture in the First Place

- The Playlist That Became a Product Catalog: Songs That Got “Commercial-Stamped”

- “Start Me Up” + the Windows 95 era: when rock swagger became a software update

- The Beatles’ “Revolution” in a sneaker campaign: the “sellout” debate goes mainstream

- Moby’s Play: when every track finds a commercial home

- Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” after a car commercial: discovery… with a side of resentment

- Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” and the cruise-commercial era: when chaos becomes vacation marketing

- Movies and TV Characters Pulled Into the Sales Funnel

- Home Alone meets smart-home tech: the nostalgia remix problem

- E.T. returns… for internet service: when emotional cinema becomes a brand vehicle

- Ferris Bueller sells a car: when “anti-establishment” gets a dealership banner

- Mean Girls goes Black Friday: when a cult comedy becomes a retail announcement

- The Shining parodies and horror icons in ads: when fear becomes flavor

- Wayne’s World and the “we know this is manipulation” era

- Memes and Catchphrases: When the Internet Joke Becomes Brand Copy

- So Did Ads Really Ruin Itor Just Change How We Experience It?

- How to Enjoy Pop Culture Again (Even After the Ad Took It)

- Experiences Related to “Pop Culture That Was Ruined By Appearing In Ads” (Extended Section)

There’s a special kind of emotional whiplash that happens when you’re having a perfectly good day and suddenly hear a

once-sacred song… only to realize your brain is now pairing it with phone plans, SUVs, or a limited-time chicken sandwich.

Congratulations: you’ve been Pavlov’d by capitalism.

To be clear, pop culture and advertising have always been in a messy situationship. Brands borrow cool; culture borrows

money. Sometimes it’s a fun cameo. Sometimes it’s a cultural crime scene: a beloved movie moment gets repurposed into a

slogan, or a meaningful song becomes “that jingle from the commercial.” This article digs into why it happens,

how it changes what we feel, and the specific examples that made audiences say, “Nooooleave my childhood alone.”

Why Ads Can “Ruin” Pop Culture in the First Place

1) Your brain loves shortcuts, and ads exploit them

Pop culture works because it carries emotional baggage: nostalgia, identity, memories, inside jokes, and the thrill of

being “in on it.” Ads don’t have time to build that from scratch, so they rent it. A familiar riff, character, or catchphrase

instantly tells your brain, “Pay attentionthis matters,” even if the product is… dental floss.

2) Association hijacking: the song becomes the product (whether it asked to or not)

Repetition does the dirty work. When you hear a song in a movie, it’s tied to story and emotion. When you hear it in a

commercial 400 times across football games, YouTube pre-rolls, and your cousin’s “totally legal” streaming site, it can

get re-filed in your memory as “the ad song.” That’s not your imaginationthat’s conditioning.

3) Meaning mismatch: when vibe and brand don’t belong in the same room

Some pop culture is built on rebellion, heartbreak, satire, or fear. Advertising is built on reassurance. When a brand

tries to slap a comforting message onto something that was never meant to comfort (or tries to make “edgy” content sell

dish soap), it can feel like watching a punk band perform at a corporate retreat. Which is… a sentence we shouldn’t have

to say, but here we are.

4) Nostalgia is powerfuluntil it gets weaponized

Nostalgia makes people feel safe, connected, and emotionally warmed up. Ads love that. But when the warm glow starts to

feel like a tactic instead of a tribute, audiences can turn on it fast. The same throwback that once felt like a hug can

start feeling like a pickpocket.

The Playlist That Became a Product Catalog: Songs That Got “Commercial-Stamped”

Music is the fastest way to borrow meaning, because it bypasses logic and walks right into your feelings like it pays rent.

Here are some of the most famous cases where a song’s cultural identity got permanently “ad-coded.”

“Start Me Up” + the Windows 95 era: when rock swagger became a software update

The Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up” already had a built-in message (“Let’s go!”) and a stadium-sized confidence. That made it

perfect for a huge tech launch. The problem? Once it becomes the soundtrack of a product momentespecially one that gets

replayed and parodiedsome listeners stop hearing a rock anthem and start hearing “reboot your computer.”

This is a classic “meaning reassignment” case. The song still exists in its original form, but your brain now carries an

extra file attachment: operating system vibes.

The Beatles’ “Revolution” in a sneaker campaign: the “sellout” debate goes mainstream

Few bands are as protected by cultural sentiment as The Beatles. So when “Revolution” showed up in a major athletic-shoe

campaign, it lit a match under a cultural argument that still hasn’t stopped burning: is licensing art “smart,” “gross,” or

“none of our business”?

The reason this one stung wasn’t just the songit was the symbolism. “Revolution” carries political and generational weight.

Pairing that with a product can feel like shrinking a big idea into a checkout-line impulse buy. Even people who didn’t mind

the campaign could understand why others felt the song’s meaning got “flattened.”

Moby’s Play: when every track finds a commercial home

Moby’s Play became famous not only for its sound, but for how widely its tracks were licensed across ads, TV, and film.

The upside: the music reached huge audiences. The downside: for some listeners, the album started to feel less like a cohesive

artistic project and more like a musical buffet for brand storytelling.

This is how “ad saturation” happens. A song can be beautiful, but if it’s attached to ten different products in ten different

moods, it can lose its emotional anchor. You’re not experiencing the trackyou’re experiencing a highlight reel of marketing

memories.

Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” after a car commercial: discovery… with a side of resentment

When a commercial introduces a new generation to a deeper cut, it can feel like a cultural winuntil longtime fans feel like

their private, delicate little universe just got turned into a public billboard. Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” is a frequent

reference point in these conversations: the song gained a surge of attention after being used in a car advertisement, and

many listeners discovered it that way.

Here’s the conflict in one sentence: discovery is good, but “my special song is now a product vibe” can feel like loss.

Nobody owns a song emotionallyyet everyone feels like they do.

Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” and the cruise-commercial era: when chaos becomes vacation marketing

“Lust for Life” has a pulse that feels a little dangerous, a little manicin other words, the exact opposite of what most

people imagine when they picture being gently rocked to sleep by an all-inclusive buffet. That’s why its use in cruise-line

advertising became such a talking point. The tension between the song’s energy and the product’s promise created a weird

cognitive mashup: rebellious punk spirit… selling leisure packages.

Sometimes that mismatch feels clever. Sometimes it feels like watching a rebellious icon get fitted for a polo shirt and asked

to “smile more.”

Movies and TV Characters Pulled Into the Sales Funnel

Movies and TV aren’t just entertainmentthey’re memory containers. Brands know that. If a song borrows emotion, a character

borrows identity. And that’s where the “ruined” feeling can hit hardest: the moment a beloved fictional world becomes a stage

for product placement (even in a standalone ad).

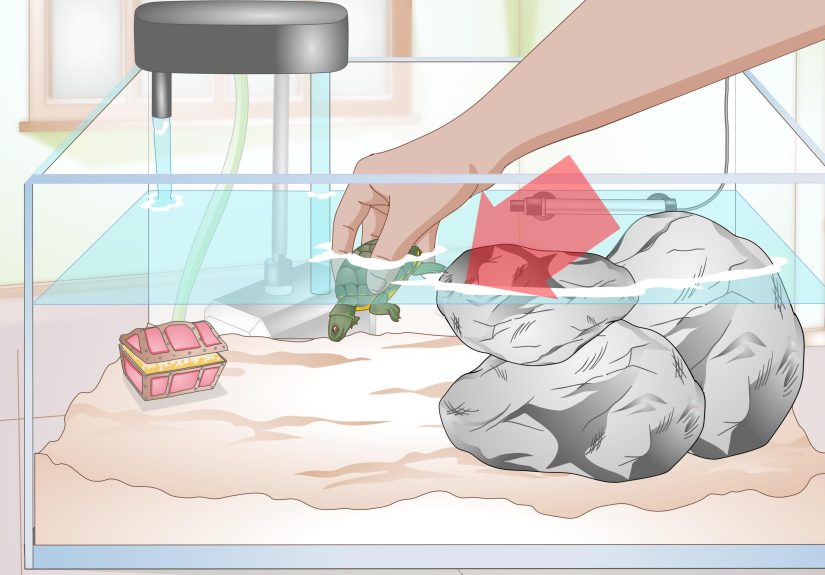

Home Alone meets smart-home tech: the nostalgia remix problem

When an iconic holiday movie gets recreated in an adcomplete with familiar setups and callback momentsit can be funny and

charming. But it can also trigger the “please don’t monetize my childhood” reflex. A story that originally worked because of

scrappy, human chaos becomes a demonstration of how many devices can be connected to your Wi-Fi.

The risk with nostalgia recreations is that they can turn a movie into a format: not a story, but a recognizable costume that

can be worn for any product. At that point, the cultural artifact stops feeling like art and starts feeling like a reusable

template.

E.T. returns… for internet service: when emotional cinema becomes a brand vehicle

The return of a beloved character can be heartwarminguntil the brand presence becomes impossible to ignore. When an ad leans

heavily into the emotional language of a classic film, some viewers feel grateful for the nostalgia, while others feel like

the movie’s sincerity is being used as a delivery system for a sales pitch.

That split reaction is the tell: it means the cultural object still matters enough to fight over. If no one cared, no one

would be mad.

Ferris Bueller sells a car: when “anti-establishment” gets a dealership banner

Ferris Bueller’s whole appeal is mischievous freedomdodging rules, skipping obligations, living like the world can’t catch

him. That energy is hard to translate into an ad without changing it. Once the character becomes part of a sales narrative,

the rebellion can feel… managed. Like it got scheduled in a marketing calendar between Q2 goals and brand lift metrics.

Mean Girls goes Black Friday: when a cult comedy becomes a retail announcement

Mean Girls is one of those movies that lives on through quotes, memes, rewatches, and the sacred ritual of texting your

friend “On Wednesdays, we wear pink” like it’s a constitutional amendment. So when the cast and characters get revived to

promote a shopping event, the reactions are predictable: delight, cringe, and the quiet realization that nothing is safe.

The “ruined” feeling here isn’t about the movie losing qualityit’s about the quote losing intimacy. When a line you used with

friends becomes retail copy, it can start to feel less like a shared joke and more like an audio logo.

The Shining parodies and horror icons in ads: when fear becomes flavor

Horror is especially vulnerable to advertising mashups because it relies on tension and atmospheretwo things ads usually

undercut with punchlines. When a terrifying movie becomes a comedic set for selling snacks or soda, some viewers love the

parody… and others feel like the original mood got deflated like a balloon at a kid’s party.

Wayne’s World and the “we know this is manipulation” era

Some commercials don’t even pretend anymorethey wink at the audience and say, “Yes, we are using your memories. Please laugh,

then purchase.” That self-awareness can be entertaining, but it can also accelerate the “ruined” effect. Once a beloved

character becomes a recurring commercial guest star, the character’s identity can start to feel like a mascot instead of a

person in a story.

Memes and Catchphrases: When the Internet Joke Becomes Brand Copy

Memes are built for speed: a shared reference that spreads because it’s funny, weird, or painfully accurate. Brands love memes

for the same reason teenagers love theminstant recognition. The problem is that marketing timelines move slower than the

internet’s sense of humor. That’s how you get “hello fellow kids” energy: a brand showing up to the party after everyone has

already left, stacking chairs, and calling it “engagement.”

How meme-marketing “ruins” a joke

- It makes it official. A meme feels like community play; an ad makes it feel like corporate property.

- It drains the edge. Jokes that worked because they were raw or absurd get sanded down to be “brand-safe.”

- It overexposes it. Once every company uses the same format, the meme stops being funny and starts being background noise.

The result is a familiar cultural sadness: you see a meme you loved, but now it’s wearing a lanyard and asking you to scan a

QR code.

So Did Ads Really Ruin Itor Just Change How We Experience It?

Here’s the fair point: pop culture isn’t a museum. It’s a living, remixable thing. Artists license music for reasons that can

be practical, strategic, or personal. Movie studios sign brand deals because the entertainment economy is expensive. And audiences

are not a single hive mindsome people find these ads delightful, others find them unforgivable, and many feel both within the

same 30 seconds.

The deeper issue isn’t “ads are evil.” It’s that advertising changes context. And context is where meaning lives.

When context shifts from story to sales, your emotional relationship with the pop culture object can shift toosometimes subtly,

sometimes permanently.

How to Enjoy Pop Culture Again (Even After the Ad Took It)

1) Reclaim the full context

If a song got stuck as “the commercial song,” listen to the whole album or watch the original performance. Let the art take up

more space in your head than the product does.

2) Make a new association on purpose

Play the song while doing something meaningful (a road trip, a workout you’re proud of, cooking with friends). Your brain can

be re-trainedyes, even after the ads got there first.

3) Separate “I’m annoyed” from “it’s ruined”

Sometimes you don’t hate the pop culture itemyou hate the repetition. That’s not the song’s fault. That’s frequency. Your

annoyance may fade once the campaign stops following you across the internet like a polite but relentless ghost.

4) Let people enjoy things (including licensing)

You can roll your eyes at a brand-cameo without shaming an artist for getting paid. If anything, the modern media economy has

made licensing a major tool for creators to keep working.

Experiences Related to “Pop Culture That Was Ruined By Appearing In Ads” (Extended Section)

If you’ve ever felt personally betrayed by a commercial, welcomeyour membership card is invisible and your dues are paid in

emotional damage. This “ruined by ads” feeling shows up in surprisingly everyday ways, and it usually starts with an innocent

moment: you’re at a grocery store, minding your own business, and suddenly a song you once loved comes on. For half a second,

you’re back in the era when you discovered ityour old headphones, your favorite playlist, that exact season of life. Then your

brain adds the sequel you didn’t ask for: a mental image of a brand logo, a celebrity smiling too hard, and some voice-over

promising “unlimited” everything.

One common experience is the “broken spell” moment. You’ll be watching a movie scene that used to hit you right in the feelings

maybe it’s tender, maybe it’s epicand you realize the same music is now tied to a product. It’s not that the scene becomes

bad. It’s that your attention splits. Half of you is trying to feel the story, and the other half is going, “Why am I thinking

about car financing right now?” That split-second interruption is often what people mean when they say a piece of pop culture

got ruined: the art still works, but your brain now has pop-ups.

Another super relatable experience is “quote contamination.” A friend drops a classic line from a beloved comedysomething that

used to be an inside jokeand you both laugh, but then someone else goes, “Oh, like that commercial!” Suddenly, the quote doesn’t

feel like it belongs to the friend group anymore. It belongs to the public. It belongs to the algorithm. It belongs to a brand’s

social media manager named Todd who schedules jokes three weeks in advance.

People also talk about the “holiday hijack,” where seasonal favorites become ad soundtracks so aggressively that the music feels

less like celebration and more like a shopping instruction. You’re trying to enjoy a cozy momentlights, cocoa, whatever your

vibe isand the soundtrack instantly reminds you of sales events and shipping deadlines. It can make you feel like the calendar

isn’t yours anymore; it’s a marketing funnel with ornaments.

Then there’s the “nostalgia reboot whiplash.” You see a beloved character return after years away, and your first reaction is

genuine joyuntil the product reveal lands and your joy has to share a couch with cynicism. Many viewers describe this as a

weird kind of grief: not because the original is gone, but because the return feels transactional. Like the character didn’t

come back to tell a story; they came back to close a deal.

And finally, there’s the experience that ties all the others together: feeling like your attention is constantly being rented.

When pop culture appears in ads, it can create the sense that nothing stays “just for fun.” Songs become selling tools. Movies

become marketing assets. Memes become corporate language. Over time, that can make people guard their favorite things more

fiercelybecause the moment something becomes widely usable in advertising, it often becomes widely repeatable, and

repetition is how magic turns into wallpaper.

The good news? Even when ads hijack a cultural moment, you can still reclaim it. Pop culture is bigger than the campaigns that

borrow it. The original song still hits when you hear it in the right context. The movie still works when you’re immersed.

The meme is still funny when it lives in the community that created it. Ads can change your first association, but they don’t

get to own the last oneunless you let them.