Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Guitar Tablature Is (and Isn’t)

- Before You Start: Your Tab Writer’s Toolkit

- 13 Steps to Write Guitar Tablature

- Step 1: Write the tuning first (always)

- Step 2: Decide which direction your strings run

- Step 3: Set the tempo, time signature, and feel (if it matters)

- Step 4: Add bar lines and sections

- Step 5: Write the notes in small, readable chunks

- Step 6: Use spacing to show timing (and don’t freehand chaos)

- Step 7: Write chords by stacking numbers vertically

- Step 8: Mark common techniques with standard symbols

- Step 9: Add bends, vibrato, and articulations clearly

- Step 10: Notate rhythm (yes, even in tab)

- Step 11: Indicate picking, muting, and percussive hits when needed

- Step 12: Choose positions that make sense on a real guitar

- Step 13: Play-test, clean up, and add “human” instructions

- A Quick “Clean Tab” Checklist

- Common Mistakes (So You Don’t Accidentally Invent a New Genre)

- Specific Examples: Turning a Riff Into Readable Tab

- Extra: Real-World Experiences (The “I Learned This the Hard Way” Section)

- Conclusion

Guitar tablature (“tab”) is the musician’s version of leaving yourself a really good note. Not a vague,

“Remember the riff thingy,” but a clear, playable roadmap: which string, which fret, what technique,

and (if you do it right) when everything happens.

If you’ve ever tried to learn from a tab that looks like it was typed during mild turbulenceno bar lines,

random numbers, mysterious letters, and the occasional “???”this guide is your antidote.

Below are 13 practical steps to write tabs that other guitarists can actually play… including future-you.

What Guitar Tablature Is (and Isn’t)

A standard tab staff uses six horizontal lines that represent the six guitar strings. Numbers on a line tell

you which fret to press on that string. A “0” usually means an open string. Simple, fast, and extremely guitar-brained.

The catch: tab often doesn’t automatically show rhythm the way standard notation does. You can write

rhythm into tab (and you should), but if you only write fret numbers, you’re basically handing someone a sentence

with no punctuation and saying, “You’ll figure it out.”

Before You Start: Your Tab Writer’s Toolkit

- Your guitar (bold choice, but recommended).

- A metronome or click (rhythm problems love dark rooms and no accountability).

- Something to write with: paper, a notes app, or tab software.

- A clear goal: Are you tabbing a riff, a full song, a solo, or a fingerstyle arrangement?

13 Steps to Write Guitar Tablature

-

Step 1: Write the tuning first (always)

Put the tuning at the top of the tab. Standard tuning is usually written as:

E A D G B e (low to high). If you’re in Drop D, DADGBe, Open G, or anything spicy,

say it up front so nobody plays your masterpiece in the wrong universe. -

Step 2: Decide which direction your strings run

Most modern tabs place the high e string on top and the low E string on bottom.

Keep it consistent and label the strings. Consistency is the difference between “helpful tab” and “escape room.” -

Step 3: Set the tempo, time signature, and feel (if it matters)

If your part is rhythm-dependent (most music is), add a tempo marking (e.g., ♩ = 120)

and a time signature (e.g., 4/4, 6/8). If there’s a swing feel, shuffle,

or a specific groove, note it. This is where “sounds right” becomes “plays right.” -

Step 4: Add bar lines and sections

Use vertical bars | to divide measures and label sections like Intro, Verse, Chorus.

Your reader should be able to find “the part after the second chorus” without needing a detective badge. -

Step 5: Write the notes in small, readable chunks

Start with one phrasetwo measures, maybe four. Write what you can play cleanly at a steady tempo.

If you can’t play it, it’s hard to guarantee your tab is right (unless you’re transcribing from a recording

then you’re allowed to be wrong briefly, as a treat). -

Step 6: Use spacing to show timing (and don’t freehand chaos)

In tab, spacing is a big deal. Notes that happen together should align vertically. Notes that happen later

should be spaced to the right. If you cram everything together, you’ll accidentally invent a new time signature.(That’s a simple chord movement example. Notice how each chord stack lines up vertically.)

-

Step 7: Write chords by stacking numbers vertically

For simultaneous notes (chords or double-stops), stack the fret numbers on top of each other.

If a string isn’t played, you can leave it blank or mark it with an x (muted). -

Step 8: Mark common techniques with standard symbols

Tabs become dramatically more playable when you notate technique. Common conventions include:

h (hammer-on), p (pull-off), / and (slides),

b (bend), r (release), ~ (vibrato), and text like P.M.

(palm mute) or let ring.Tip: Be consistent with symbols. If you write “H” once and “h” elsewhere, it’s still readable,

but it looks like your tab is arguing with itself. -

Step 9: Add bends, vibrato, and articulations clearly

When bending, specify the target (half-step, whole-step, etc.) if you can. Some tab writers use

7b9 to show a bend from fret 7 up toward the pitch of fret 9. For vibrato, a ~

is common. If a note should ring out, write let ring or use a line. -

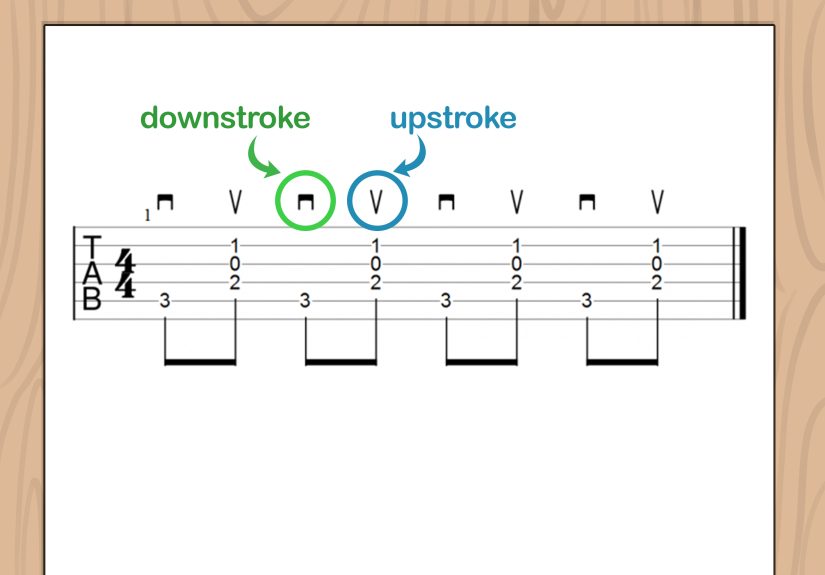

Step 10: Notate rhythm (yes, even in tab)

If you want your tab to survive outside your own brain, you need rhythm cues. Options:

- Stem/rhythm notation above tab (most precise, often done in tab software).

- Count marks (e.g., “1 e & a”) above tricky passages.

- Consistent spacing with clear bar lines (minimum viable rhythm).

Here’s a simple way to add a count above the tab for a syncopated figure:

-

Step 11: Indicate picking, muting, and percussive hits when needed

If a riff depends on palm muting, write it. If it’s all downstrokes, say so. If there are muted “chucks,”

mark them with x. These details are often the difference between “close enough” and “oh, THAT riff.” -

Step 12: Choose positions that make sense on a real guitar

Many notes can be played in multiple places. When you write tab, you’re also choosing a fingering.

Aim for what’s playable at tempo, not what’s technically possible in a slow-motion physics demo.

If a lick jumps from 2nd position to 12th for no musical reason, your reader will assume you’re trolling.Pro move: if there are two valid options, add a small note like “play in 5th position” or

show the shift with a slide/position marker. -

Step 13: Play-test, clean up, and add “human” instructions

Play your tab exactly as written. If you trip, your reader will trip. Fix alignment, confirm technique marks,

and add short notes like “repeat 4x,” “build intensity,” or “let chords ring.” The goal isn’t to be fancy

it’s to be un-misunderstandable.Final check: Can another guitarist sight-read it at a slow tempo and recognize the part? If yes, you win.

If not, adjust rhythm cues and technique markings.

A Quick “Clean Tab” Checklist

- Tuning is labeled at the top.

- Strings are ordered consistently (and labeled).

- Measures are divided with bar lines.

- Notes that happen together align vertically.

- Rhythm is shown via spacing, counts, or notation.

- Techniques (h, p, slides, bends, vibrato, muting) are marked consistently.

- Sections, repeats, and endings are labeled clearly.

- The tab has been play-tested.

Common Mistakes (So You Don’t Accidentally Invent a New Genre)

1) Writing fret numbers without rhythm

A string of numbers might be correct… and still unplayable as intended. Add counts for tricky syncopations,

and use bar lines like your life depends on it.

2) Misaligned timing

If the bass note of a chord lines up with the next measure while the top notes line up with the previous one,

your tab will feel like it’s wearing two different shoes.

3) Over-symbolizing everything

Symbols are greatuntil your tab looks like it’s trying to summon a guitar spirit. Mark what matters:

articulation, muting, slides, bends, and anything that changes the sound noticeably.

Specific Examples: Turning a Riff Into Readable Tab

Let’s say you have a simple lick on the top strings with a hammer-on and a slide. Write it as a short phrase,

add bar lines, then annotate techniques:

Notice what’s doing the heavy lifting: the bar lines, the consistent spacing, and the technique marks.

You’re not just telling someone what notes happenyou’re telling them how they happen.

Extra: Real-World Experiences (The “I Learned This the Hard Way” Section)

The first tab I ever wrote looked “fine” until someone tried to play it. That’s when I discovered a law of nature:

your tab is only as good as the stranger who can play it without texting you.

I had written the right notes… but I hadn’t written the music. No rhythm. No phrasing. No “this note rings while

the next one happens.” Just numbers, floating like lonely islands.

My next attempt was the opposite problem. I added every symbol I’d ever seen: bends, releases, vibrato marks,

tiny slides, “let ring,” and (in a moment of panic) a few extra dashes that I hoped would imply groove.

The result wasn’t clearerit was busier. A friend called it “guitar algebra.” Fair.

That’s when I learned a second law of tab-writing: clarity beats completeness.

If the bend is the hook, notate it. If the tiny micro-slide doesn’t change how it sounds, let it go.

Rhythm was the biggest breakthrough. I started writing tabs with a metronome and counting out loud.

If I couldn’t count it, I couldn’t tab it. For syncopated riffs, I’d write “1 e & a” above the measure and place

the notes under the syllables where they actually happened. Suddenly, the tab stopped being a guess and became a

performance notelike “hit this here, not whenever your soul feels ready.”

Position choices were another lesson. I used to tab everything “as low as possible” because it looked simpler.

But some riffs only feel right in a specific position because of tone, vibrato, and the way the hand sits.

I once tabbed a lead line in three different spots on the neck and couldn’t figure out why it sounded “off”

until I realized the original player was using a higher position so the notes could sing with easier vibrato.

Now, when I write tab, I think like a guitarist, not a calculator: what would your hand naturally do at tempo?

The best habit I’ve built is play-testing like I’m my own worst critic. I’ll slow it down, play it exactly as written,

and ask: “Would a decent guitarist interpret this correctly without hearing the song?” If the answer is “maybe,”

I add a count, a technique mark, or a two-word instruction like “palm mute” or “let ring.” If the answer is “no,”

I rewrite the measure. The goal isn’t to make the tab fancyit’s to make it reliable.

And honestly? Writing tab made me a better player. It forced me to listen to articulation, timing, and technique,

not just pitch. When you try to explain a riff on paper, you learn what’s actually happeningwhere the slide starts,

whether that note is picked or hammered, how long the chord rings. Tab isn’t just a way to share music.

It’s a way to understand it.

Conclusion

Writing guitar tablature is part documentation, part translation, and part “please don’t make future-me guess.”

Start with tuning, keep your measures organized, align your notes, and add technique + rhythm cues where they matter.

Your tabs don’t need to be perfectthey need to be playable.