Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Intel Shows Up at Every Retro Party (Even If You Didn’t Invite Them)

- The Original “Drop-In Upgrade” That Turned Heads: The NEC V20/V30

- The Clone Wars: AMD, Cyrix, and the Art of “Compatible, But Faster”

- How to Break x86 the Fun Way: Undocumented Behavior, Timing Tricks, and Demoscene Mischief

- Microcode: The Tiny Firmware You Never See (Until You Suddenly Care a Lot)

- FPGAs, Emulators, and Reimplementations: When the CPU Becomes a Project

- Staying on the Right Side of the Line: Clean-Room Thinking for Retro Folks

- Retro Projects That Scratch the Itch (Without Summoning Corporate Thunder)

- Field Notes From the Retro Trenches: of “Making Intel Mad” Energy

- Conclusion: Rebellion, But Make It Educational

Retrocomputing is supposed to be relaxing: a warm mug of nostalgia, a floppy drive that chatters like a polite woodpecker, and a beige tower that weighs as much as your regret. But every now and then, the hobby takes a mischievous turnlike discovering that the fastest way to learn how the PC world really works is to poke the places where it’s historically been touchy.

Which brings us to a delightfully nerdy thought experiment: how do you “make Intel mad”not by trolling customer support, but by exploring the technical and legal pressure points that shaped the IBM PC ecosystem? The twist is that we’re doing it retrocomputing edition, where the weapons of choice are socketed CPUs, clean-room documentation, undocumented behaviors, and the kind of timing-sensitive code that makes emulators sweat.

This isn’t a guide to starting a corporate feud. It’s a guided tour through the weird corners of x86 historywhere “compatible” is a battlefield term, microcode is both magic and litigation bait, and a chip swap can feel like you just committed a tiny act of rebellion… with an anti-static wrist strap.

Why Intel Shows Up at Every Retro Party (Even If You Didn’t Invite Them)

If your retro target is an IBM PC, a PC/XT, a PC/AT, or most DOS/Windows-era compatibles, you’re orbiting the gravitational pull of x86. Intel’s 8086/8088 lineage became foundational once IBM chose the 8088 for the original PC platform, and the long-term consequence was an ecosystem where software compatibility became the most valuable currency in personal computing.

That compatibility isn’t just about instruction mnemonics on a cheat sheet. It’s about a stack of expectations:

- ISA behavior (the visible “language” of the CPU)

- Microarchitecture quirks (timing, prefetch behavior, odd corner cases)

- Microcode (internal control routinespart firmware, part secret sauce)

- Platform glue (chipsets, buses, BIOS interfaces, and all the awkward handshakes)

Retrocomputing thrives on these details. Preservation demands accuracy, and accuracy demands curiosity. The moment you chase “why does this demo only work on a real 5150?” or “why does this game crash on one 486 but not another?” you’re studying the boundary between what Intel documented and what Intel merely did.

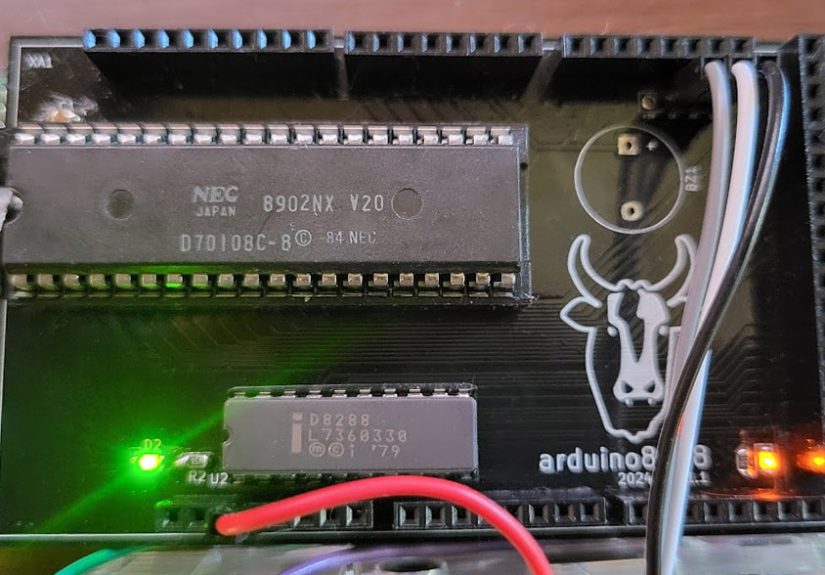

The Original “Drop-In Upgrade” That Turned Heads: The NEC V20/V30

If you want a single, iconic example of retro “Intel irritation,” it’s the NEC V20 (and its sibling, the V30). In the early IBM PC era, these chips became famous as drop-in replacements for the Intel 8088/8086 familyoften faster clock-for-clock, sometimes more efficient, and loaded with compatibility tricks that made hobbyists grin.

Why the V20 Was Such a Big Deal

For a lot of early PCs, upgrading meant buying a whole new system. The V20 was the opposite: pop the CPU, press in the new one, and suddenly your vintage machine felt like it drank an espresso. Some variants even offered a mode that could run 8080-style softwarea little party trick that widened the “what can this old box do?” horizon.

To retrocomputing folks, the V20 is practical joy. To a dominant architecture owner, it’s the uncomfortable reminder that “compatible” is both a technical claim and a legal grenade.

Microcode: Where Engineering Meets Courtroom Vocabulary

The V20 era also highlights a long-running tension: microcode is internal, but it matters. In disputes about CPU cloning, microcode gets described not as a mystical electrical aura but as something closer to a programand that framing changes the legal stakes. The history around microcode disputes is a big reason later competitors leaned heavily on clean-room techniques and careful process documentation.

Retro takeaway: the V20 isn’t just a faster chipit’s a living artifact from the era when x86 compatibility became serious business, and “I made it run the same software” could trigger years of legal chess.

The Clone Wars: AMD, Cyrix, and the Art of “Compatible, But Faster”

Retrocomputing often romanticizes “the one true chip,” but the PC world was never that tidy. Intel’s dominance was realyet the ecosystem constantly tested how far compatibility could stretch across different manufacturers.

AMD: Second-Source Roots and a Long Road to x86 Independence

Long before AMD became the household-name rival you see in modern gaming rigs, it played a key role as a second-source manufacturer in the early microprocessor economy. Over time, licensing, arbitration, and court decisions shaped what AMD could build, how it could build it, and what “rights” meant in practice when the CPU’s internals (including microcode-related issues) became contentious.

From a retro angle, AMD’s story is a reminder that “compatible” didn’t just happen because engineers were clever. It happened because contracts, court rulings, and painstaking independent development created space for competitors to exist without instantly imploding in lawsuits.

Cyrix: Performance, Personality, and an Inbox Full of Lawsuits

If AMD’s history is a slow-burning saga, Cyrix is the punk-rock chapter. Cyrix built x86-compatible CPUs that often targeted the value/performance sweet spot, and its path collided repeatedly with Intel in court. For retrocomputing fans, Cyrix chips are fascinating precisely because they’re “nearly the same” while also being not the sameand that small difference is where the technical lore lives.

Want to “make Intel mad” in retro terms? Boot a finicky DOS game on a Cyrix system, watch one timing edge-case wobble, and realize you’re seeing the consequence of two different companies trying to implement the same software-facing promise through different hardware realities.

How to Break x86 the Fun Way: Undocumented Behavior, Timing Tricks, and Demoscene Mischief

Retrocomputing isn’t only about running spreadsheets the way your ancestors intended. It’s also about pushing machines past the polite boundaries of “supported.” And nothing highlights those boundaries like timing.

8088 MPH and the Art of Humiliating Emulators

The demoscene production 8088 MPH became legendary because it extracts effects from the original IBM PC that feel impossible on paper: dazzling visuals from CGA, clever sound from the PC speaker, and tricks that depend on the kind of cycle-level behavior that most emulators historically treated as “close enough.” The demo’s fame is partly artisticand partly because it serves as a public exam for anyone claiming they emulate an IBM 5150 accurately.

This is “making Intel mad” in spirit: it’s not about attacking a company. It’s about using deep knowledge of the platform’s behaviordown to prefetch and signal quirksto prove that the real machine is stranger and more capable than simplified models suggest.

Undocumented Doesn’t Mean Unimportant

Intel (and everyone else) documented what most developers needed. But retro software preservation often cares about edge cases no one wanted to support forever: timing sensitivities, weird flags behavior, and “don’t do this” instructions that demo coders promptly do anyway. Once you care about perfect authenticity, you start appreciating that the ISA is only the beginning of the story.

Microcode: The Tiny Firmware You Never See (Until You Suddenly Care a Lot)

Microcode is one of those concepts that sounds theoretical until it becomes practical. In simple terms, microcode helps implement complex instructions using sequences of internal operations. That internal layer has been both a powerful engineering tool and a frequent source of secrecyand therefore friction.

Why Microcode Makes People Nervous

For manufacturers, microcode is part of the implementation advantage: it can hide complexity, enable updates, and patch certain classes of issues. For researchers and historians, microcode is a key to understanding what a CPU truly doesand why “compatible” is sometimes more nuanced than a marketing badge suggests.

Modern security research has also shown that microcode update mechanisms, encryption, and validation are not just abstract. When researchers reveal more about how updates work, it changes what’s possible for analysis, verification, and (in the wrong hands) mischief. Retrocomputing doesn’t need to cross that line to benefit: the big lesson is that CPUs aren’t static artifacts. Even “hardware” can have a firmware-like layer with rules and constraints.

FPGAs, Emulators, and Reimplementations: When the CPU Becomes a Project

Here’s where retrocomputing gets spicy: the moment you stop merely using vintage hardware and start recreating it. Modern retro scenes thrive on:

- Cycle-aware emulators that aim for behavioral accuracy

- FPGA recreations that reproduce vintage CPUs and systems at a hardware-description level

- New builds that combine old-school interfaces with modern components

This is also where the legal/PR temperature can rise, because companies have historically guarded x86-related intellectual property closely. Intel has, at various times, publicly emphasized that x86 is proprietary and that unauthorized implementations or emulation attempts may raise IP concerns. Whether any specific project is legally risky depends on what it copies (patented ideas? copyrighted code? protected microcode?), what it merely imitates (behavioral compatibility), and how it was developed.

Retro rule of thumb: independent creation, clean-room practices, and avoiding proprietary code are not just good ethicsthey’re practical survival skills for anyone building compatibility projects.

Staying on the Right Side of the Line: Clean-Room Thinking for Retro Folks

You don’t have to be a corporation to learn from corporate survival tactics. Clean-room methodologyseparating “spec writers” from “implementers,” documenting behavior rather than copying codehelped shape the PC clone industry, especially around BIOS compatibility. The same mindset applies if you’re writing an emulator core, building a compatible board, or documenting chip behavior for preservation.

Important note: This is not legal advice. But the retro-friendly principle is simple: prioritize interoperability and historical accuracy, and avoid copying proprietary code or protected microcode. If your project could be described as “I dumped a ROM and shipped it,” you’re probably stepping where you shouldn’t.

Retro Projects That Scratch the Itch (Without Summoning Corporate Thunder)

If your goal is the fun of boundary-pushingnot the dramahere are practical ways to channel “Making Intel Mad” energy into projects that are more about learning than legal brinkmanship:

1) Do the V20 Swap on a Real IBM PC/XT-Class Machine

It’s one of the most satisfying upgrades in the hobby because it’s tactile, historically authentic, and immediately noticeable. You’ll also learn quickly that “compatible” can still have quirksespecially if you test oddball software, copy-protected games, or timing-sensitive demos.

2) Explore Non-Intel x86 Systems as First-Class Retro Targets

Build a period-appropriate machine around a Cyrix or AMD chip and treat it as a legitimate branch of PC history, not a footnote. Try the same DOS games, the same drivers, the same weird utilities. Where does behavior match perfectlyand where does it drift? That drift is where the history lives.

3) Study Demos That Depend on Hardware Truth

Run productions like 8088-era demos on real hardware and then compare with different emulators. When something breaks, don’t just shrugtrace it. Learn what assumption the emulator made, and what the original machine actually does. That’s preservation work disguised as entertainment.

4) Build Accuracy Into Your Tools

Whether you’re writing a small emulator, a CPU test suite, or a timing benchmark, you’re contributing to the ecosystem. The best retro tools are the ones that can tell you not only “it works,” but also “it works for the right reasons.”

Field Notes From the Retro Trenches: of “Making Intel Mad” Energy

The first time you do a CPU swap on a vintage board, you realize how much of modern computing is hidden behind sleek packaging. A socketed chip is honest. It just sits thereceramic or plastic, little notch for orientation, pins daring you to bend themand it forces you to participate. You ground yourself, you pry carefully, you line up the notch, and you press down like you’re sealing an oath. When the machine boots afterward, it feels less like “turning on a computer” and more like “successfully reanimating a small museum exhibit.”

Then you start testing. Of course you do. You run a familiar DOS tool, a benchmark that’s older than some internet memes, and maybe a game that once made you believe 16 colors was plenty. And when the numbers jumpeven a littleyou grin. Not because you’ve beaten Intel in any meaningful way, but because you’ve proven that the PC’s history was never a single-lane road. Someone, decades ago, engineered a chip that could walk into Intel’s neighborhood, speak the same instruction-set language, and still have its own accent.

The real fun begins when you chase the weird stuff. You load a demoscene production and watch it behave like a truth serum. One emulator nails the intro but stumbles later. Another gets the visuals mostly right but the timing feels off. On real hardware, the effect snaps into placelike the code was written by someone who didn’t just read a spec sheet, but listened to the machine’s heartbeat. That’s when you understand the retrocomputing mindset: accuracy isn’t pedantry. Accuracy is respect for the original constraints, the original tricks, and the original humans who figured out how to do magic with almost nothing.

Eventually you find yourself talking about microcode at a normal speaking volume, which is how you know you’ve gone deep. You’ll read chip histories the way other people read mystery novels. You’ll learn that compatibility was negotiated in courtrooms as much as in labs. You’ll discover that “clean room” isn’t just a phraseit’s a survival technique that let whole branches of computing exist without being sued into vapor. And you’ll start to appreciate the strange irony of retro work: to preserve old machines faithfully, you sometimes have to reverse-engineer them more thoroughly than anyone did when they were new.

At some point, you’ll be at a swap meet or scrolling listings late at night, and you’ll spot the exact CPU you’ve been reading about. You’ll feel a ridiculous rushlike you’ve found a rare trading card, except the card can run Lotus 1-2-3. You’ll bring it home, clean the pins, and install it with the careful reverence usually reserved for old vinyl records. And when it boots, you’ll smile againnot because you made Intel mad, but because you made history audible. The fans spin, the screen flickers, the speaker clicks, and a machine from another era proves it still has stories left to tell.

Conclusion: Rebellion, But Make It Educational

“Making Intel Mad” works best as a playful metaphor for what retrocomputing already does naturally: it questions assumptions, tests boundaries, and preserves truth in the details. Whether you’re swapping in a legendary compatible CPU, studying demoscene code that exposes hardware realities, or building tools that chase cycle-level accuracy, you’re participating in the living history of the PCone that has always included competitors, clones, and clever hacks alongside the official timeline.

And if that occasionally ruffles feathers in the mythology of “one true platform,” well… that’s just retrocomputing doing its job.