Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Dead Bug” Construction Really Means

- Why a Timer Relay Is the Perfect No-PCB Project

- The Core Idea: A “Timer + Driver + Relay” Stack

- Dead Bug Layout Rules That Make It Work (and Keep It Working)

- Choosing Parts That Behave in “No PCB” Builds

- A Practical Example: Dead Bug 555 Timer Relay (Delay-On)

- Common Mistakes (a.k.a. Why Your Relay Is Clicking Like It’s Auditioning for Tap Dance)

- Testing and Troubleshooting Without Fancy Gear

- When “No PCB” Is the Best Choiceand When It Isn’t

- of Real-World Experience: The Stuff You Only Learn After You’ve Melted Something Once

- Wrap-Up

Waiting for a PCB can feel like watching paint dryexcept the paint costs money, arrives late, and you still

have to drill holes. If you just need a timer relay that works right now, the “dead bug”

build style is your fast lane: no etched board, no layout software, no “why is my ground pour shaped like a

regret?” moments.

In this guide, we’re going to unpack how to build a dead bug timer relay using classic, reliable

building blocks (hello, 555 timer), how to drive a relay safely (hello, flyback diode), and how to make the whole

thing sturdy enough to survive real life. The goal: a clean, repairable, point-to-point timer relay that needs

no PCBjust good habits and a little patience.

What “Dead Bug” Construction Really Means

“Dead bug” (often lumped into “ugly construction”) is a prototyping technique where componentsespecially ICsare

physically attached to a copper-clad board (or another base) and wired point-to-point. The IC is

frequently glued upside down so its leads stick up like tiny legs… hence the name. It looks chaotic, but

electrically it can be excellent: short connections, easy rework, and a ground plane you can trust.

Think of it as the “campfire cooking” version of electronics. A PCB is a full kitchen. Dead bug is a cast-iron

pan and confidence.

Why a Timer Relay Is the Perfect No-PCB Project

A time-delay relay circuit is basically three friendly chunks:

(1) a timing brain, (2) a driver muscle, and (3) a switch.

It’s low part count, forgiving in layout, and easy to troubleshoot with a basic multimeter. In other words: it’s

exactly what you want when you’re building without a printed circuit board.

The Core Idea: A “Timer + Driver + Relay” Stack

1) The timing brain: monostable vs. astable

For a timer relay, the most common approach is a monostable timer: you trigger it, the output goes

high for a set period, then it returns low. The 555 timer is famous here because it’s cheap, widely available,

and tough enough to survive beginner mistakes (within reason… it’s still not a superhero).

In a classic 555 monostable, the pulse width is approximately:

t ≈ 1.1 × R × C. That single equation is why people keep a 555 in the drawer “just in case.”

Want 10 seconds? Choose an R and C that multiply into roughly 9.09 seconds, then let the 1.1 factor do the rest.

Want 2 minutes? Same gamejust bigger values, and a little more patience.

2) The driver muscle: turning a tiny signal into relay coil current

A relay coil is an inductive load. It wants real current, not a polite suggestion. Even if your timer output can

source or sink decent current, a transistor or MOSFET relay driver is usually the smarter move:

it protects the timer, keeps heat down, and makes the behavior more predictable.

The basic pattern is simple:

a low-side switch (NPN transistor or N-channel MOSFET) connects the relay coil to ground when “on.”

Then you add the most important tiny part in relay world:

a flyback diode across the coil (reverse-biased during normal operation).

When the coil turns off, the diode gives the current somewhere safe to go instead of letting the coil create a

voltage spike that tries to haunt your circuit.

3) The switch: contacts that actually handle the real-world load

The relay contacts are where projects go from “cute bench demo” to “actual device.”

If you’re switching anything significantmotors, transformers, solenoids, or mains voltageuse a relay with

appropriate ratings, a proper enclosure, strain relief, fusing where appropriate, and spacing that respects

electricity’s favorite hobby: arcing.

Also: inductive loads don’t just kick the coil side. They can stress the contacts too.

Depending on the load, you may need a snubber network, MOV, or other contact protection to reduce arcing and noise.

(If that sentence felt like a boring safety lecture, goodboring is the goal when you’re dealing with sparks.)

Dead Bug Layout Rules That Make It Work (and Keep It Working)

Use copper-clad as a ground plane

If you’re building on copper-clad board, treat that copper as your ground plane. It’s the closest thing you have

to a “real PCB feature,” and it’s incredibly helpful for stability. You can solder ground connections directly to

it and keep return paths short.

Keep the relay loop tight and away from the timing node

The relay coil current loop (supply → coil → transistor → ground) is noisy compared to the timing capacitor node.

Don’t run those wires side-by-side like they’re best friends. Give the timing capacitor and threshold/trigger pins

a quieter neighborhood, or the circuit may “mysteriously” retrigger. (Electronics mystery translation:

the layout is gossiping.)

Decouple like you mean it

A small bypass capacitor near the timer IC’s power pins is not optional if you want clean behavior. Dead bug builds

can have short wires, but they can also have weird stray inductance and “creative” grounding. Decoupling helps the

IC see a stable supply even when the relay kicks on and off.

Strain relief: the unglamorous hero

Point-to-point wiring is only as reliable as your mechanical support. If a wire can wiggle, it will. If it can

fatigue, it will. Anchor heavier wires, support the relay body, and avoid using component leads as structural beams.

If you’re mounting in an enclosure, add proper strain relief so the outside world doesn’t yank your solder joints

into an early retirement.

Choosing Parts That Behave in “No PCB” Builds

The timer IC

A standard 555 (NE555/LM555 family) is a go-to for short to moderate delays. For longer delays (minutes to hours),

you can still use a 555, but component tolerance and leakage become more noticeable. If you need long, repeatable

timing, a CMOS counter/oscillator approach (or a microcontroller) can be more stablethough it adds complexity.

The timing capacitor (where accuracy goes to negotiate)

Electrolytic capacitors can vary widely, and they can drift with temperature and age. That doesn’t mean “don’t use

them”it means “don’t promise your timer is accurate to the millisecond.” If you need better accuracy, consider

film capacitors for smaller values and keep leakage paths clean and short.

The relay + driver

Pick a relay coil voltage that matches your supply (5V, 12V, 24V are common). Then choose a driver that comfortably

handles coil current with margin. Add the flyback diode across the coil. If you need faster relay release (for

timing precision or contact behavior), you can use alternatives to a plain diode clamp (like diode+zener or active

clamp approaches), but keep it simple unless you truly need the speed.

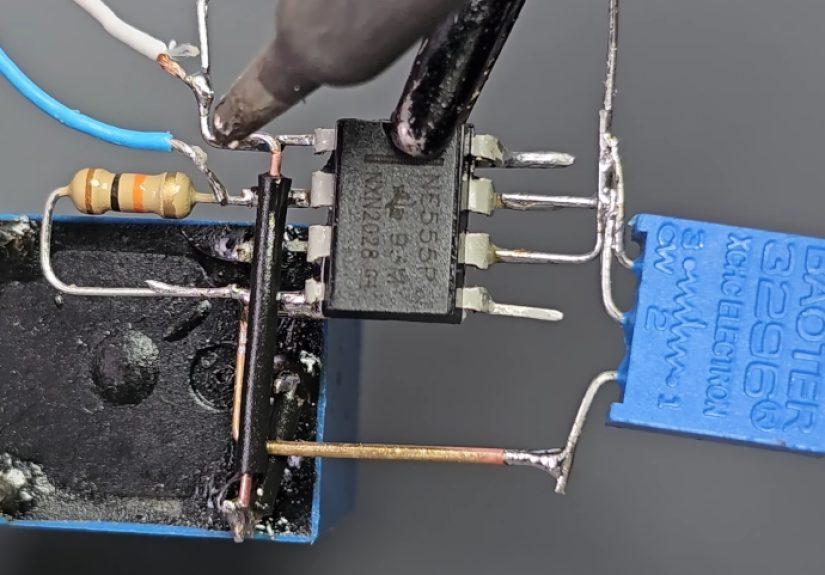

A Practical Example: Dead Bug 555 Timer Relay (Delay-On)

Here’s a concrete, easy-to-visualize build that works well in dead bug form:

Conceptual parts list

- NE555/LM555 timer IC

- Timing resistor (R) + timing capacitor (C) chosen for your delay

- NPN transistor (or logic-level N-MOSFET) as a relay driver

- Relay (coil matches your supply voltage)

- Flyback diode across the relay coil

- 0.1 µF decoupling capacitor near the 555

- Optional: a button or trigger input, and an LED indicator with a resistor

How it behaves

You apply power. You trigger the circuit (button, sensor, or control signal). The 555 output goes high for

approximately t ≈ 1.1RC. During that window, the transistor turns on, energizing the relay coil.

When time expires, the output drops low, the transistor turns off, and the relay releases.

Dead bug-friendly wiring tips

-

Glue the 555 upside down to your base (copper-clad is ideal). Keep its ground pin extremely close to the ground

plane connection. -

Place the timing capacitor physically close to the 555 pins it connects tothis is a “quiet” node and benefits

from short leads. -

Put the relay and transistor together in a “noisy corner,” and route only the control line from the 555 output

to that corner. - Solder the flyback diode directly across the relay coil pins if you canit’s neat and minimizes loop area.

Common Mistakes (a.k.a. Why Your Relay Is Clicking Like It’s Auditioning for Tap Dance)

1) Missing or backwards flyback diode

If the relay coil doesn’t have suppression, your driver can see a nasty spike at turn-off. Sometimes it survives.

Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes it “sort of works” and then fails when you show it to someone. (Electronics have

a flair for drama.)

2) No decoupling capacitor near the timer

Relays pull current. Supplies sag. Grounds bounce. A 555 can misbehave if the supply is noisyespecially in

point-to-point builds. A small bypass capacitor near the IC reduces false triggering and jitter.

3) Long leads on the timing capacitor node

Long leads add noise pickup and leakage paths. Keep that node short, clean, and away from relay wiring.

4) Assuming time is “precise” with big electrolytics

If your timing capacitor is a large electrolytic, your delay will likely be “close enough” rather than “lab grade.”

Calibrate by measurement, and leave headroom if timing matters.

Testing and Troubleshooting Without Fancy Gear

-

Verify supply voltage under load: measure VCC while the relay is energized. If it dips a lot,

your timing can shift or the 555 can glitch. - Check the 555 output pin: confirm it goes high for the expected duration after trigger.

-

Measure the timing capacitor voltage: in monostable mode, it should charge toward a threshold

and then discharge when the timer resets. -

Confirm the driver stage: make sure the transistor is saturating (BJT) or fully enhancing

(MOSFET) so the relay coil gets full current.

When “No PCB” Is the Best Choiceand When It Isn’t

Dead bug construction is fantastic for one-offs, prototypes, repairs, and “I need it by tonight” builds. It’s also

surprisingly educational: you feel current paths, you learn layout discipline, and debugging becomes more

intuitive.

But if you’re shipping units, operating in harsh environments, or switching anything hazardous, a properly designed

PCB (or a certified module) can offer better repeatability, creepage/clearance control, and mechanical stability.

Dead bug is a tooluse the right one for the job.

of Real-World Experience: The Stuff You Only Learn After You’ve Melted Something Once

The first time I built a dead bug timer relay, I was convinced the “no PCB” part would be the hard part. Turns out,

the hard part was my optimism. I glued the 555 down, wired the timing network, hooked up a relay, and… it worked.

For about ten minutes. Then it started retriggering like it was haunted. The fix wasn’t mystical: I had routed the

relay coil wires right alongside the timing capacitor lead, basically inviting noise to crash the party. Moving two

wires and adding a proper bypass capacitor made the “ghost” vanish instantly.

The second lesson was about glue. “Any glue will do,” I told myself, which is a sentence that has never ended well

in human history. Some adhesives stay rubbery, some get brittle, and some don’t love heat. If the relay or a power

resistor runs warm, cheap glue can soften and let parts drift. After redoing a build that slowly sagged into a

shorts-and-sparks situation (not recommended), I started treating mechanical mounting as part of the circuit design,

not an afterthought.

Then there’s the “electrolytic reality check.” On paper, the timing math looks clean. In real life, a big

electrolytic capacitor has personality: leakage, tolerance, and temperature behavior. I once “designed” a 60-second

delay that behaved like a 45-second delay in a warm room and a 70-second delay in a cooler one. The fix wasn’t to

complain at the capacitor (though I tried). It was to measure, calibrate, and pick parts with better stabilityor

accept that this timer was for humans, not for atomic clocks.

The most useful habit I picked up was building in test points on purpose. In dead bug construction, it’s easy to

tack a tiny loop of wire onto VCC, ground, the 555 output, and the timing capacitor node. Those little loops make

troubleshooting dramatically faster. When something goes wrong, you can measure quickly without poking the circuit

like a cat testing whether a glass will fall off the table.

Finally, the “relay side” taught me respect. The coil side is mostly about protecting your electronics (flyback

diode, clean power, good driver). The contact side is about protecting your world: correct ratings, proper

insulation, and sensible enclosure choices. The best timer relay in the universe isn’t worth much if the wiring is

loose, the load is underrated, or the device lives naked on a workbench where it can be bumped. Dead bug builds can

be rugged, but only if you design for real handlingstrain relief, mounting, and enough spacing that nothing is

relying on luck to stay safe.

After a few builds, the “no PCB” approach stops feeling like a compromise. It starts feeling like a superpower:

fast iteration, easy fixes, and a circuit you understand because you literally built every connection by hand. Just

remember: neatness isn’t about aestheticsit’s about making the electrical behavior predictable and the physical

build durable. The timer relay doesn’t care if it’s pretty. It cares if the electrons can find their way without

chaos.

Wrap-Up

A dead bug timer relay is one of the best proofs that you don’t need a PCB to build something

reliable. Use a solid timing core (like a 555 monostable), drive the relay correctly (transistor + flyback diode),

keep your layout disciplined (quiet timing node, tight coil loop, good decoupling), and mount it like you expect

gravity and vibrations to exist (because they do). Do that, and you’ll have a no-PCB timer relay that’s fast to

build, easy to debug, and satisfying in that “I made this with my hands” kind of way.